Other segments from the episode on March 24, 2014

Transcript

March 24, 2014

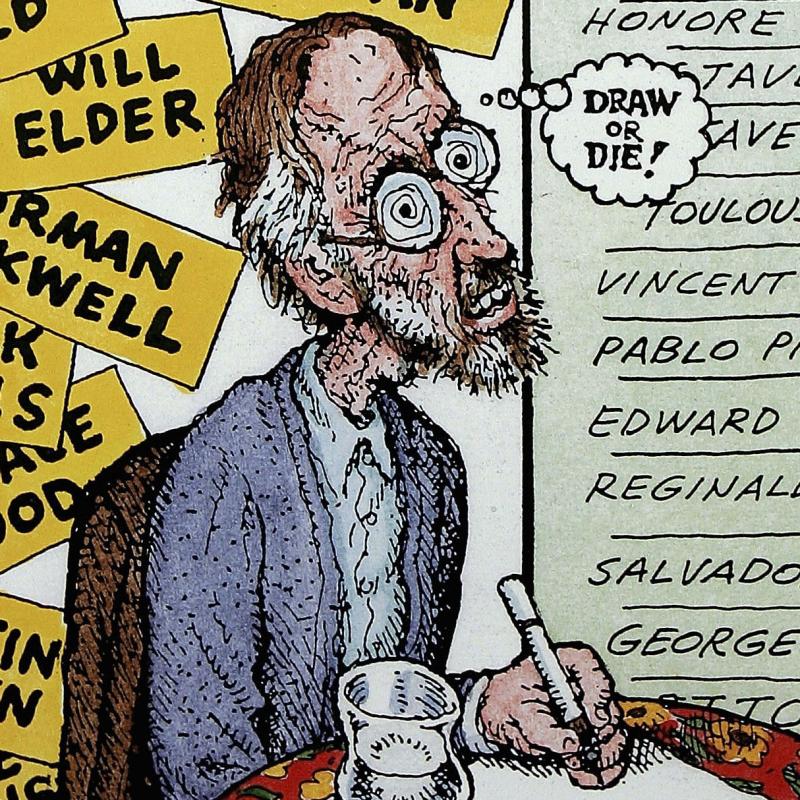

Guest: Robert Mankoff

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. If you love New Yorker cartoons, you'd probably love the view from Bob Mankoff's desk. As the cartoon editor of the magazine, he evaluates more than 500 cartoons every week. He became the cartoon editor in 1997, 20 years after selling his first cartoon to the magazine.

I'll describe the cartoon he's most famous for. An executive is at his desk, on the phone, looking at his calendar saying no, Thursday's out. How about never? Is never good for you? The title of his new memoir is taken from that caption. It's called "How About Never - Is Never Good for You?: My Life in Cartoons." Bob Mankoff's book is filled with cartoons and insights about them.

Bob Mankoff, welcome back to FRESH AIR. So, do you remember how you came up with the idea about how about never, is never good for you?

BOB MANKOFF: I absolutely do, which is unusual, because, you know, as I told people a lot of times, people think you get one idea for a cartoon every week, and that's not the way it works. You usually get 10 or 15, and you're - certainly when I was a cartoonist, before I was a cartoon editor, you're rushing to do what is called the batch. When I was doing that, I liked to have, in general, about 10 cartoons.

And people say, well, why, you know, new cartoonists especially ask me: Why do you want me to do 10 cartoons every week? I say because nine out of 10 things in life don't work out. So I had done nine cartoons, and I was looking to do one more. I was trying to get on the phone, and I did get on the phone with a friend of mine, quote-unquote "friend," who I wanted to see. And somehow, that person didn't want to see me, it seemed.

And, you know, I kept saying, well, could we do it this time? Could we do it that time? And then I just got exasperated with him and said: How about never? Is never good for you?

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: So it was really a snotty line, and when I look back on it, on my Queens and Bronx and New York Jewish background, it's sort of like, hey, if I never see you again, it'll be too soon. The underlying structure is that. So I do remember it. And I didn't think anything of it, really, except this was the last thing in a batch, I was going to throw it in, and, you know, it's a quip.

And it's an executive on the phone, looking at the appointment book, saying that, so I sort of switched the position so that the guy saying it is in a position of superiority rather than inferiority, because it makes it funny. So I handed it in in 1993. At that time, the editor, art editor and cartoon editor, was Lee Lorenz - still a wonderful cartoonist for us - and the editor was Tina Brown.

And so the next day, Lee calls me back and says: We want that cartoon for A issue. A issue is the next issue that's coming out, and usually, that really is only for cartoons that are completely topical because, you know, why do you need it right away? I mean, cartoons, often, that you do for the New Yorker don't appear for months afterwards, and the record for that is a cartoon that was bought by James Stevenson in 1987, and didn't appear until 2000.

So I said, well, why does Tina want this right away? He said because she loves this cartoon. She just thinks this is a great cartoon. And, you know, it turned out to be the most - one of the most reprinted cartoons in, I think, New Yorker history, we don't have records going all the way back, and certainly my most reprinted cartoon and certainly - yeah, it's a little macabre. I mean, don't think most people know what's going to be in their obituary, but I do.

GROSS: Oh, yeah, but not on your tombstone, right?

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: Not on my - well, Johnny Carson had: I'll be right back.

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: Which seemed very optimistic.

GROSS: So...

MANKOFF: Yeah. So, yeah.

GROSS: So what are some of the ways that how about never, is never good for you has been appropriated over the years?

MANKOFF: Well, you know, just to get this right, I'm going to look in the book to see what Nancy Pelosi actually said, but when she was on the Jon Stewart show, she said, just talking back and forth to Jon Stewart, when the Republicans came in, they said to the president: How about never? Does never work for you? The other ways it's been appropriated is, of course, just being reprinted in and of itself. It's on coffee mugs. It's also been ripped off. It's on panties.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Great.

MANKOFF: Yeah. So, there, you know, and I - really no higher praise.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: And but, you know, my lawyers are after it. We've recalled all those panties, and...

Seriously?

MANKOFF: No.

GROSS: Oh.

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: What do you want to do with recalled panties, really? They sound...

GROSS: Well, no, if it's a copyright infringement, it's a copyright infringement. Do they ask for your permission to reprint it on...

MANKOFF: No, they don't, and a lot of these things are...

GROSS: And they were really more like thongs, judging from the photo in your book.

MANKOFF: That's right. You know what? You're right, thongs. That's right.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Just to be precise.

MANKOFF: I stand corrected.

GROSS: Slightly harder to fit it onto a thong than a full panty, yeah.

MANKOFF: And I hope people are enjoying them.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: No, they're not enjoying them, because it's how about never.

MANKOFF: No, actually, you know, it's impossible to track those things down, you know, because they're all run by the Russian mafia. No, that's not true.

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: But the - and you really don't want to mess with them. And it's just not worth it. I think at one time, before the Internet, you sort of could do that. But now it's sort of piracy becomes the sincerest form of flattery.

GROSS: So, in your book, you write that you have to look at about 500 cartoons a week and...

MANKOFF: Right.

GROSS: Because you're the cartoon editor at the New Yorker. And you say evaluating humor is different from enjoying humor. And to demonstrate, you have a cartoon with 10 possible captions. And this is what you have to do all the time for the cartoon caption contest that you run each week, where you put a cartoon on the page, and readers have to come up with captions, and it's a contest, and you reprint the winners.

MANKOFF: Right.

GROSS: So this cartoon that you reprint with 10 possible captions is two snakes walking side by side, and one of them, in the middle of the snake body, has a bulge that looks like two buttocks.

MANKOFF: Very callipygianous buttocks.

GROSS: Oh, callipygianous, what does that mean?

MANKOFF: Right. It means very well-shaped buttocks.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Thank you.

MANKOFF: So now you can - I don't know how often you can use that in conversation without getting slapped.

GROSS: OK. So, I want you to read the 10 possible captions.

MANKOFF: OK, so the captions are: Did you see the look on Darwin's face? I don't like the way Adam looks at you. That happens when you eat Brazilian. Now you probably want a chair. Those Kardashians are hard to swallow. I'm telling you, the apple will be tempting enough. It's hot now, but tomorrow it'll be somewhere near your ankles. All he gave me to work with was a lousy apple. I told you silicon was non-digestible. It's not my fault that my brain is not evolutionarily wired to like that. Please stop asking, honey. If anything you look too thin. If only I had hands, Gladys, if only I had hands.

So there you have all the choices. And one of the things, you know, this book, the paradox of choice, one of the things about choice in humor and just the interference of the judgment process is it automatically is a mediating response, and it short-circuits your laugh response. Now, instead of laughing at something, as you would in a normal cartoon, you're having to judge it. And, for one thing, that makes everything less funny, but you still have, you know, you still have to judge it.

GROSS: So which did you pick? Which did you think was the funniest?

MANKOFF: You know, I thought the funniest was: I don't like the way Adam looks at you.

GROSS: I thought the funniest was: Did you see the look on Darwin's face?

MANKOFF: But you see, you're wrong.

GROSS: Why am I wrong?

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: No, you're not. So, humor itself and your response to humor, that's one of the things that, really, I learned in doing this job and even writing this book, especially the caption contest, is very, very varied. And there's a huge amount of variability between subjects, and there's even great variability within a person.

At another time, you might choose something different. So, you know, probably because you're smart and intellectual, and you like that association with Darwin, you know, I think that's why that worked for you. But what we do is after we look through all 5,000 - and usually it's my assistant, and usually the assistant is someone from the Harvard Lampoon - looks through all 5,000, categorizes them in all different ways the jokes are made, then I pick maybe these many, and I use Survey Monkey, and I send it out to the New Yorker editors.

And just like you, the response is incredibly varied. But at that point, it's sort of this - it's this crowd-sourcing. And you know what? I'll sort of tend to go with the one that the crowd likes at that point because in the end there's another crowd who's going to pick, who vote on it. But all of these - one of the things is all of these are actually pretty good when you look at it, what the caption contest is, which is a game.

So I try to evaluate it not so much as is this hysterically funny, but if you were playing this game like a board game, and you came up with this, would you think you did a pretty good job? I think for all of these you'd think I did OK.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Bob Mankoff. He's a New Yorker cartoonist and the cartoon editor at the magazine. He has a new memoir that's about his life but also about the art of cartooning. It's called "How About Never - Is Never Good for You?: My Life in Cartoons." Let's take a short break.

MANKOFF: You see those two snakes? That might have worked for the two snakes, too.

GROSS: How about never?

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: That would be funny.

MANKOFF: Well see?

GROSS: That actually works for so many things.

MANKOFF: Right, and of course the caption contest, I won't go there, but one of the interesting things about the caption contest is that it showed first of all that a sense of humor and especially a sense of humor related to cartoons is something really that's very, very widespread. It doesn't mean that the people who win the contest are professional cartoonists, but a lot of what the Internet is showing is that talent is more disperse than gatekeepers such as myself, you know, previously restricted it to.

And the other interesting thing about the caption contest is that it spawned all forms of meta-humor so that there's an anti-caption contest where you come up with the worst possible caption. There's the universal caption contest where you come up with a caption that fits all of the contest, and one of the contenders is what a misunderstanding.

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: And the other is, I don't know if you can have this on NPR, is Christ what a (beep).

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: And so - and I think the interesting thing about that, the interesting thing about this is people will laugh much harder often at these than they will at the actual caption. And that shows something about the shifting character of humor in our society. It's become much more ironic. It's become much more humor about humor. And I don't think there's ever been as much meta-humor, jokes about jokes, sort of ironic stances from humor than there has been, and that's partly what I talk about in the book.

GROSS: It's time to take that break, so let's take a break, and then we'll talk some more. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Bob Mankoff. He's been a cartoonist with the New Yorker since the late '70s. He's also been the cartoon editor for many years. Now he has a new memoir called "How About Never - Is Never Good for You?: My Life in Cartoons."

You know, in giving advice to you about cartoon humor, you mentioned, like, if you're doing a list or mentioning alternatives that there's got to be at least, that two isn't enough. And I've heard comics, standup comics talk about the law of threes. So what's the magic of three?

MANKOFF: I think the magic of three is sort of what I talked about before in terms of surprise. You need a sequence for surprise. So let's, you know, look at a joke by Alex Gregory. You know, it's two cavemen, and, you know, they're saying I don't understand it, the air is pure, everything we eat is organic, and yet we only live to 30.

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: Or another one this is a great cartoon by Alex Gregory, which also really shows this thing that in professional comedy is called a triplet, which is one, two and then boom, the punch line. A woman is saying I started my vegetarianism for moral reasons, then for health concerns, and now it's just to annoy people.

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: So by setting it up - and also the two things about it is that the final thing, the final part, the punch line always must diminish. It can't raise; it can't elevate. I did a cartoon that's a little bit like that, but it's a visual cartoon in which it shows three doors, and we're looking, you know, left to right. So the first door is accounting department, the second door is legal department, and the third door is jail.

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: So one, two, three. So you're always looking at - I mean, you are ridiculing something. You are making fun of something. That's really the fun of humor. There is humor that's just whimsy, that we smile at, but the humor that we laugh at, someone has to be - someone's dignity has to be reduced.

GROSS: How have New Yorker cartoons changed since you started cartooning for the magazine in around '77?

MANKOFF: I think they've changed, and for one reason they have become sort of meta. You know, so when you look back at desert island cartoons, which we've had forever, you know, you might have, you know, a cartoon with - well, it's interesting. The very first desert island cartoons are rather big. You've got to live on that island, OK.

By 1984, I have a cartoon where the guy is pretty much, he's a regular-sized guy, but he's the size of the island, and he's saying no man is an island, but I come pretty damn close.

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: And then maybe a few years ago I have a cartoon by Farley Katz where there's Superman on the island, and he's saying wait, I can fly. So...

GROSS: Oh, I get it, OK. That took a second, all right.

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: Wait, I can fly. So that's really sort of more meta - it's a cartoon about cartoons. When you look back at the older cartoons, they're very much more observational cartoons. And the cartoon, the people in the cartoons are not making the joke. They're not making the joke. So in an older cartoon you might have, and this is based on more stereotypes than we would have had then, you might have a woman at a baseball game, she's looking exasperatingly at her watch, and she's saying why didn't they tell us there would be an extra inning, you know, because...

GROSS: Right.

MANKOFF: OK, she's not making a joke. She is saying this - she's saying this. We're observing the joke. In these later cartoons like the one about vegetarianism and the like, it's like sitcom, right. There's no way that she's not aware that this is a joke. And I think one of the reasons that humor changes is because of the humor that the generations are exposed to. So the generations that were exposed to sitcom have the people actually saying the line, saying the joke, whereas sort of before that you have much more observational humor.

Also the humor is much more absurd, as the humor in - you know, maybe it all started with - it's a Monty Python-type influence. So whereas previously you might have a cartoon where there's the damsel on the railroad tracks being tied down, you know, by the villain, and maybe it's a Charles Adams cartoon, and he's doing a sailor's not or some, you know, that might be the joke, whereas a Zack Cannon(ph) cartoon recently, there's a cartoon called "Paninis of the Old West." And the villain is tying down paninis on the railroad track.

GROSS: So is that funny, or is that just silly?

MANKOFF: I think it's both. It is silly, it is silly but in an inspired way, you know, and more and more cartoons are sort of like that. But I think one of the things, one of the things I enjoyed in writing this book is really showing the very, very widespread type of humor that happens in New York. You have completely silly cartoons, but then you have cartoons that are satiric, but it's interesting because they're - they do deal with issues that are in the public mind, but they're never really about the public figures.

So if they're cartoons about same-sex marriage, I'll give two examples, one is a Michael Short(ph) cartoon where it's a couple looking at TV, and the guy is saying gays and lesbians getting married, haven't they suffered enough?

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: And then I did a cartoon where there's a couple in bed, and the guy is saying to the woman: What's your opinion on some-sex marriage?

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: So it's refracted through the personal, and I think the interesting thing about New Yorker humor is that it's basically benign. I know everybody wants humor to be subversive and speak truth to power. I don't think power has been listening, incidentally. But the humor in the New Yorker is the jokes are directed back at the class that's reading the magazine. And for me personally that's the most interesting type of humor.

GROSS: Bob Mankoff will be back in the second half of the show. He's the cartoon editor of the New Yorker. His new book is called "How About Never -- Is Never Good for You?: My Life in Cartoons." I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross back with Bob Mankoff. He's been a cartoonist for the New Yorker since 1977 and has been the magazine's cartoon editor since 1997. His new memoir takes its title from the caption of his most famous cartoon. It's called "How About Never - Is Never Good for You?: My Life in Cartoons."

So, you write a little bit about different editors of The New Yorker...

MANKOFF: Right.

GROSS: ...that you've worked under. And when you joined the magazine in the '70s, William Shawn was the editor, and he's famous for being very circumspect about anything sexual. It was hard to get anything sexual into the magazine. And so you write...

MANKOFF: You would not have a callipygianous snake.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: That's right.

MANKOFF: No way. Yeah.

GROSS: You write, for Shawn, any suggestion of real sex was taboo. But when Tina Brown was editor - and this was starting in the '90s?

MANKOFF: Ninety-one, I believe.

GROSS: Yeah. When she was editor, the propriety pendulum swung in the other direction. So while pendulum swung in the other direction, did you do any cartoons that you think would never have made it under Shawn?

MANKOFF: Yeah. I did a cartoon which Tina bought, with a guy saying to his wife in bed, they're both reading, and he's saying: You're right. Tonight isn't reading night. Tonight is sex night.

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: So that would never, you know, I don't - none of the cartoons that I ever did, you know, are, you know, basically, if they're about sex, they're about sex in sort of this, you know, ironic way, or the way that people actually treat it. So I think Tina really opened up the magazine in a necessary way. And maybe the pendulum did go, you know, too far. You know, under Tina, we bought a joke where a guy is getting an exam, and the doctor has the rubber glove, and the guy who's about to get that exam is saying: Does this make me your bitch?

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: And I think that's...

GROSS: That's hysterical.

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: I know, but it just seemed - one of the things is, The New Yorker is, very, very - the The New Yorker in a - I point this out in the book. It's an empathetic environment. It's not a - that is hysterical, but it might not be hysterical in The New Yorker. It might not be hysterical in a magazine that might...

GROSS: But you bought that one, right?

MANKOFF: We did.

GROSS: Yeah.

MANKOFF: We did. Tina bought it. But, just to show you how sensitive the, you know, the readers of The New Yorker can be, I mean, I talk about this within the context of one of the theories of humor called Benign Violation. And Benign Violation - to make it, to shorten it - is, you know, Las Vegas had that ad: Just the Right Amount of Wrong?

GROSS: Yeah.

MANKOFF: Well, that's how jokes work, right? But Just the Right Amount of Wrong is different in different contexts. And, for instance, even in cartoons that we print - OK, here's one, and here's, like, the reaction. And we printed this cartoon. So, there's two surgeons, and there's a child on the table. And one surgeon is saying to the other: There's got to be an easier way to get candy from a baby.

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: And we got so many letters from people, you know, saying: Do you know how widespread child abuse is, and how many children are injured or die? And I do think it perfectly OK to run that cartoon, because, really, these cartoons are a complete fantasy. There are no surgeons. No one is getting hurt. Or another example is a cartoon that we ran in which it's lab technicians, and they're looking at a rodent, and then the rodent has hung himself. And the caption is: discouraging data on the antidepressant.

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: You know, OK, so one of these things - so all of those work, but we get many, many letters saying: I don't think that's funny. I don't like to see animals suffer. I don't like to see them suffer, even in cartoons.

GROSS: But, really, can you let that guide you? Because there are some people who have, like, no sense of humor at all, and they're hypersensitive about things to...

MANKOFF: We don't...

GROSS: Yeah.

MANKOFF: We don't let that guide us.

GROSS: OK.

MANKOFF: But we don't let that guide us. But, on the other hand, we are aware of people's sensitivities. So after some terrible tragedy in which guns are used, we're not going to have any gun cartoons in the magazine that week.

GROSS: Sure. Well, that's different. Yeah.

MANKOFF: You know, OK. So, but I mean, I...

GROSS: I mean, I think it's different. Yeah.

MANKOFF: It is different. But it's a continuum. Do you know what I mean? It's...

GROSS: Yeah. So, where's the pendulum under you? If the pendulum was, like, no sex under Shawn and be more transgressive under Tina...

MANKOFF: Well, let's - well, wait a second.

GROSS: Yeah.

MANKOFF: It's not under me. It's under David Remnick. He is the ultimate...

GROSS: Oh, sure. OK. Right. Yeah.

MANKOFF: He is the ultimate...

GROSS: Yeah.

MANKOFF: I think, for me, I've become a little bit more sensitive. I don't - what I never want to do is offend intentionally.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

MANKOFF: I don't want to be that the purpose of it. But if it's something like this that - and you're not offending intentionally, and that you have to understand that humor itself shouldn't be a scapegoat for essentially everything in entertainment. We watch thrillers and murder mysteries and "CSI" and Shakespeare, and all sorts of horrible things are happening. One of the things you realize is that humor is a coping mechanism. We have so many cartoons about the Grim Reaper because, OK, death is the ultimate reality, and one of the ways we cope with our anxiety about death and illness is actually through humor. Some of the cartoons that I like the most are just, you know, Grim Reaper cartoons. So, one of my of mine that I think is pretty good in which the Grim Reaper is taking away the husband, and the woman's at the apartment door, and she's saying, relax, Harry. Change is good.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Bob Mankoff. He's a cartoonist for The New Yorker. He's been cartooning for them since 1977. He's also the cartoon editor of the magazine, and now author of the new memoir, "How About Never - Is Never Good for You?: My Life in Cartoons." This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. And if you're just joining us, my guest is Bob Mankoff. He's been cartooning for The New Yorker since about '77. And he's also the long-time cartoon editor of the magazine. Now he has a new memoir called "How About Never - Is Never Good for You?"

You have a whole chapter in the book devoted to people who say I don't get it to New Yorker cartoons that elicit that response. There was even a storyline - as you point out in your book - in an episode of "Seinfeld," where Elaine's complaining that she doesn't get a cartoon in The New Yorker, and then, you know, she tries to write one herself.

MANKOFF: Right.

GROSS: Why is it that you get that response so much? And what's your reaction? Do you try to explain, well, here's where the joke is? Does it make you think that it was a bad cartoon when people say they don't get it?

MANKOFF: Well, I mean, I think one of the things is - just to bring this up, interestingly, is that the - that episode was written by Bruce Eric Kaplan, a New Yorker cartoonist. So Bruce...

GROSS: A very funny one. He's great.

MANKOFF: Yeah. He's a wonderful, wonderful, you know, he's a wonderful cartoonist. And really - now, of course, Elaine's cartoon, you know, it's actually like this old anti-joke, where it sounds like a joke, and she has a pig at a complaint department saying: I wish I were taller. So it's really a non-joke, right?

GROSS: Right.

MANKOFF: It's a non-joke. You know, we actually ran that as a real caption contest, and I think the winner was: Stop sending me spam.

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: Which is...

GROSS: Right.

MANKOFF: ...an actual joke. One of the things I do, you know, I try to show in the book is that there's lots of different types of humor. They're sort of very, very - there's humor based in reality. So it might be a William Hamilton cartoon. William Hamilton draws these rather stuffy, upper-class rich people. And it might be a guy at dinner saying to a younger man: Money is life's report card. So we understand it's a quip, right?

GROSS: Yeah.

MANKOFF: And it's an observation, and it absolutely could happen. OK. And sort of everybody will get that type of joke. Everybody will get the type of joke where it's a standard gag which a woman is saying: Yeah, he had deep pockets, but his arms were short. OK.

GROSS: Right.

MANKOFF: So you put it together. Then, as you go up in what I call playful incongruity or absurdity, you'll have another cartoon that pretty much everybody will get, but it's not in the realm of reality anymore. It's a cowboy at a desk, OK. The person sitting in front of him is not a person, but a cow, and he's reading his resume. So, everything about this cannot happen. And he's saying, very impressive. I'd like to find 5,000 more like you.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Yeah.

MANKOFF: OK. So that's it. Another example of that would be a doctor - and this is also by Leo Cullum, who did that - a doctor, and he's examining a cow. The cow has the bell around his neck, and the doctor is saying, I think I can help with that ringing in your ear.

GROSS: Ah. Uh-huh.

MANKOFF: OK. Those are jokes.

GROSS: Right.

MANKOFF: Everybody understands them, and they might like them or not like them. Going up the absurdity thing, you might have a receptionist, and on the intercom is coming over, Ms. Banks, I'm going to need a hacksaw, some green glitter and a flounder for my four o'clock. OK. So that's...

GROSS: Right. The silence is I don't get it. Yeah.

MANKOFF: But you might. But people will laugh at that. It's just putting together. It's sort of - but here's a personality characteristic. The type of people who will laugh at that, that that won't mean that they won't laugh at standard jokes. But when we do psychological studies of this, we find that those type of people are more open to experience in general. They...

GROSS: Are you saying I'm not open to experience?

MANKOFF: You are absolutely open to experience. I'm saying a lot of the jokes that you laughed at - the meta-humor, the sort of silly things, like, I would say like paninis of the old West...

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

MANKOFF: That's sort of a crazy joke, right?

GROSS: Yeah.

MANKOFF: I mean, you said it's silly, but you laughed at it. So, it doesn't have a lot of what's called closure, this thing like I absolutely get it. It's more like you go through the flow and you enjoy it. So that's the range of types of things in the magazine, and on that end of it, you see where people say, I don't get it. On the other hand, those are some of the cartoons that people enjoy the most.

GROSS: So let's talk about you.

MANKOFF: OK.

GROSS: Did you have anyone in your family who was a jokester - who, you know, like, told jokes at the dinner table, like maybe your father?

MANKOFF: No. My father didn't tell jokes. But as I say in the book, my father had a wry sense of humor. What I got for my mother was, like, this incredible chutzpah and flamboyance, and her speaking Yiddish and just this Jewish sense of the Yiddish - which is the sort of language of humor, in which it...

GROSS: OK. OK. Well, hold it right there because...

MANKOFF: OK.

GROSS: Because one of the things your mother used to tell you, if you said you were bored...

MANKOFF: Yeah.

GROSS: ...was that you should go bang your head against the wall, then you won't be bored. My mother used to say in Yiddish, (Yiddish spoken), or something along those lines. Which means...

MANKOFF: Right. Exactly.

GROSS: ...go bang your head against the wall.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: And she'd say that to me when I go, Mommy, I'm bored. She'd go (Yiddish spoken) or I'm sorry, I'm ruining the - killing the pronunciation. But...

MANKOFF: Right. Right.

GROSS: But, so that apparently was a really popular saying of Jewish mothers of that generation.

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: Absolutely. Because - but that - but Yiddish - and that's really just comes right from Yiddish. Yiddish is a language of humor. I mean, that's not a real statement, right? But it's both aggressive and loving and funny.

GROSS: Right.

MANKOFF: Really.

GROSS: I knew my mother didn't literally want me to bang my head against the wall.

MANKOFF: Right.

GROSS: But she was basically saying: Leave me alone and go amuse yourself.

MANKOFF: But also, she was saying something deeper, really, I think. What she was saying: boredom is a luxury.

GROSS: Oh. Oh. Oh.

MANKOFF: You know, boredom is something...

GROSS: Is that you think what your mother was saying?

MANKOFF: Yeah, in some way. My mother grew up on the Lower East Side.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

MANKOFF: She was born in 1908. She'd washed lice from her hair with kerosene. She was out with her bubbie, her grandfather, you know, when she was 3, tending a tomato stand when he went in to pee. OK, so she came from another world, and a world where hey, it's a luxury to be bored, which means you got to think of what you want to do, so go bang your head against the wall. You won't be bored. And also, the back-and-forth with my mother, and even her insulting me - because the insults are humorous. Now, I don't have the Yiddish pronunciation, when she called me (Yiddish spoken), which is a big horse, or a (Yiddish spoken), which is a little dog, or the thing she always used to call me also, which I am to this day, she would say: You're a nervous (Yiddish spoken). And that really was: You're a nervous plague.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Very nice.

MANKOFF: Very - I know...

GROSS: So...

MANKOFF: And it sounds horrible, and yet that's what I was raised at. And also, my mother - to use her words, and they apply to me, also - my mother had a mouth on her. She'd speak up. She would, you know, complain. I mean, I still remember this. She was so picky, like, when she went to a restaurant she would give these incredible orders, you know, detailed. And even before the food would get to the table, she would reject it, like an antimissile system.

(LAUGHTER)

MANKOFF: So, you know, so all of that, of course, I...

GROSS: Were you embarrassed by that? Because that could be really embarrassing when...

MANKOFF: I was completely embarrassed. But embarrassment is the mother's milk of humor, embarrassment at one time, humor later. Anything that's embarrassing is potentially funny and I think what Jewish culture taught me and what the - and Jewish culture now is everyone's culture - is all these embarrassing things, all these guilt-filled things, all these anxiety filled things are material.

GROSS: When you were in college you studied experimental psychology and you gave it up before you got your doctorate...

MANKOFF: Right.

GROSS: ...for cartooning. But now you're doing some work in that area again, doing research into what happens in the brain when somebody laughs or something along those lines. Tell us what you want to know.

MANKOFF: Yeah. I mean, I'm interested in that moment. You know, we talked about getting it. I'm interested in the get it moment that happens in cartoons. And I'm not doing really research in the brain. I did some, along with Richard Lewis, at the University of Michigan. I did this interesting study in which we did eye tracking as people looked at a cartoon and different types of cartoons.

Sometimes the cartoons - we addressed verbal cartoons and sometimes they had a visual element. And we watched their eyes. And at the moment that they get the cartoon their pupil expands almost like it would for a flash bulb. So we can sort of track the actual sort of get it moment. And that's the type of research I'm interested in. I'm interested in the caption contest and when we crowd source humor, just seeing all the different ways that people are creative using humor.

And I'm really interested in the link between creativity and humor because humor is a type of creativity and I do think that humorous people and humorous health helps creativity.

GROSS: So what do you think it might mean that the pupils dilate at that moment of I get it?

MANKOFF: It means that humor is basically this type of - it's a cognitive process. And it's a creative process not only on the part of the cartoonist but on the part of the viewer. And I think that's very interesting because I think that would be analogous to the a-ha moment in scientific invention or when you get a crossword puzzle. Arthur Koestler wrote a book "The Act of Creation" in which he connected humor and science and art.

And so I think one of the things it shows is that they are all connected.

GROSS: You have some very funny cartoons about marriage.

MANKOFF: Yeah.

GROSS: And you mention in the book you've been married three times.

MANKOFF: I have been married three times and it just keeps better and better but I'm going to stop here.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: So one of your cartoons is a man's talking to a woman over drinks and he says, look, I can't promise I'll change but I can promise I'll pretend to change. And then another one is a man talking to a woman in the living room and he says: Believe me, Janet, I consider you an important part of our marriage.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: And I'm wondering if anybody who you were previously married to took offense at...

MANKOFF: What about the person I'm now married to?

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Well, because you could always say, no, it's about my previous wives.

MANKOFF: No. Previous wives, right. Right. No, I don't think so. I mean, they - I mean, I'm making fun of myself and I think I'm making fun of all men in our desperate, desperate attempt to understand the people we're with and hopefully through humor have them understand us. And I do find that humor helps in relationships. It certainly helps in my marriage now because I'm a very, very fallible person and if I wasn't funny I'd be kicked right out the door.

GROSS: Well, Bob Mankoff, it's been great to have you back on the show. Thank you so much for talking with us.

MANKOFF: Thanks so much, Terry.

GROSS: Bob Mankoff is the cartoon editor of the New Yorker and author of the new memoir "How About Never? Is Never Good for You?" The title comes from the caption of his most famous cartoon. That's one of the cartoons you'll find on our website, along with an excerpt of Mankoff's book. That's at freshair.npr.org. Coming up, jazz critic Kevin Whitehead reviews a collection of Bud Powell recordings from radio broadcast of his performances at Birdland in 1953. This is FRESH AIR.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. The great bebop pianist Bud Powell played several engagements at the New York jazz club Birdland in 1953. Parts of those shows were carried on the radio, and one listener recorded some onto acetate discs. A new collection of those recordings has been released. Jazz critic Kevin Whitehead says the sound quality isn't much, but the music is terrific.

(SOUNDBITE OF JAZZ MUSIC)

UNIDENTIFIED MAN: Gentlemen from the stage of Birdland on Broadway at 52nd Street. Once again, welcome to the live show portion of the Birdland show right here on Broadway and 52nd Street. Listening right now to our theme done by the amazing Bud Powell, the trio, the Bud Powell Trio doing "Lullaby of Birdland."

KEVIN WHITEHEAD, BYLINE: Bud Powell had played Birdland before he opened there on February 5, 1953, but this return engagement was a big deal. That very day, he'd been discharged from a state psychiatric hospital, after being committed for a year and a half following a drug bust. Powell's mental troubles partly stemmed from a 1945 police beating in Philadelphia. He was painfully uncommunicative face to face but when he sat at the keys, it was a whole other story.

(SOUNDBITE OF JAZZ MUSIC)

BUD POWELL: Bud Powell with Oscar Pettiford on bass and Roy Haynes on drums. It's from the latest edition of the pianist's 1953 Birdland material, a three CD set from ESP. As with other versions of this material, the sound only gets cleaned up so far; filter out the surface noise and you also lose most of the cymbals. But Bud's piano punches through.

WHITEHEAD: His quicksilver lines could echo Charlie Parker's saxophone, breath pauses and all. Still, Powell's concept was deeply pianistic - he knew how to make the strings ring, and cover the keyboard. Older pianists accused beboppers of playing with only one hand. But Bud jabbing left is always part of the rhythmic conversation.

(SOUNDBITE OF JAZZ MUSIC)

WHITEHEAD: There's a recent biography of the pianist, the exhaustively researched and thoroughly depressing "Wail: The Life of Bud Powell" by Peter Pullman. It spells out what a nightmare Bud's life was at the time. While hospitalized, he was subjected to at least a dozen insulin shock treatments.

When he was released, it was into the custody of Oscar Goodstein, his legal guardian and business manager and the manager of Birdland where Bud was appearing - shades of the old plantation. Then Goodstein pushed Powell into a sham marriage to a woman he barely knew. It didn't last, but Powell was hemmed in on all sides.

(SOUNDBITE OF JAZZ MUSIC, "GLASS ENCLOSURE")

WHITEHEAD: Bud Powell named one evocative new tune "Glass Enclosure," either for Birdland's announcer's booth near the stage, or the apartment his manager warehoused him in, or maybe the invisible box that walled Bud off like a trapped mime. You can understand why Powell so needed to play, he'd nudge other pianists off the bench when he went club-hopping. The keyboard was the only place where he could fully express himself.

(SOUNDBITE OF JAZZ MUSIC)

WHITEHEAD: Bud Powell with Roy Haynes and bassist Charles Mingus. 1953 was one of Bud Powell's most productive years. Besides his series of Birdland engagements, he had some out-of-town gigs, including a celebrated Toronto concert that reunited him with his bebop peers Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Max Roach. He also recorded a batch of material for the Roost and Blue Note labels, the latter released under the rubric "The Amazing Bud Powell." The performances on "Birdland 1953" confirm that that adjective was no idle boast.

(SOUNDBITE OF JAZZ MUSIC)

GROSS: Kevin Whitehead writes for Point of Departure, Downbeat, and eMusic and is the author of "Why Jazz?" He reviewed "Bud Powell: Birdland 1953" on the ESP label.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.