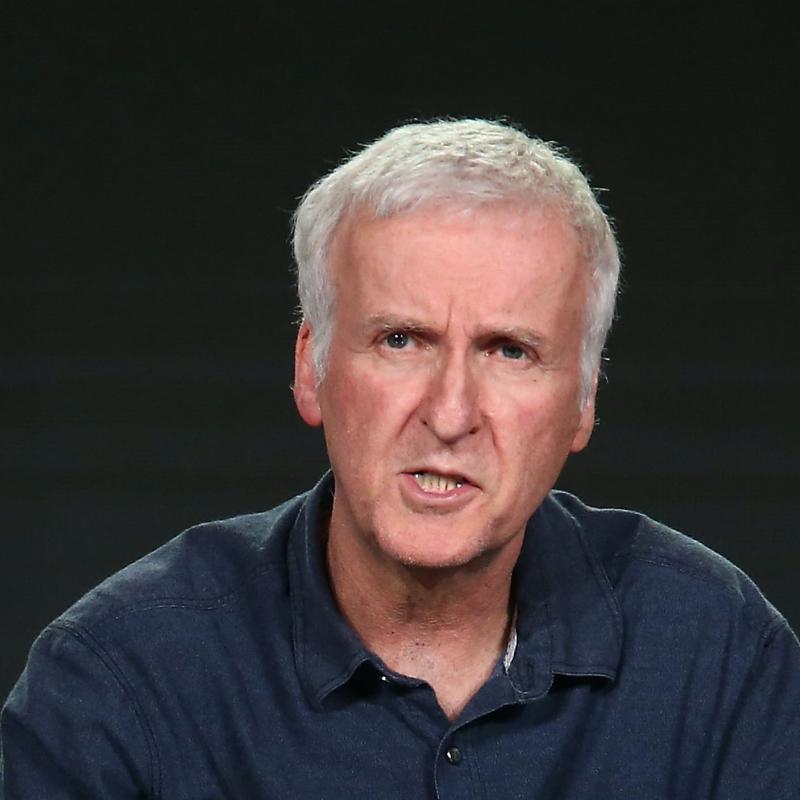

James Cameron: Pushing The Limits Of Imagination.

You might define the films of James Cameron by listing two characteristics: state-of-the-art special effects and huge box-office receipts. For starters,Titanic, The Terminator and Aliens all qualify on both counts. Now he adds Avatar to the list. He joins Fresh Air to discuss his complex special effects and innovative filming techniques.

Other segments from the episode on February 18, 2010

Transcript

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20100218

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

James Cameron: Pushing The Limits Of Imagination

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross. My guest, James Cameron, has directed the

top two highest-grossing films of all time: the 1997 film "Titanic" and, of

course, his latest, "Avatar." "Avatar" has made over $2.3 billion and has

received nine Oscar nominations, including Best Picture and Best Director.

Cameron first came up with the idea for "Avatar" 15 years ago, but he shelved

the project after realizing that the technology didn't exist to make the film.

In the intervening years, Cameron helped develop a new 3-D digital camera

system, which he used to film many underwater documentaries, as well as

"Avatar."

"Avatar" stars Sam Worthington as Jake Sully, an injured Marine who's now in a

wheelchair. He takes a job with a military contractor to work on the planet

Pandora, where the company is trying to extract a precious ore, but the natives

on the planet, the Na'vi tribe, are getting in the way. Jake's job is to be an

avatar, to take the form of one of the Na'vi and infiltrate them both for

anthropological information and to try to get them out of the way. In this

scene, he's reluctantly recording one of the first video logs about starting to

learn the Na'vi ways.

(Soundbite of film, "Avatar")

Mr. SAM WORTHINGTON (Actor): (As Jake Sully) This is a video log, 12 times 21,

32. Do I have to do this now? I really need to get some rest.

Unidentified Woman #1 (Actor): (As character) No, now, when it's fresh.

(Soundbite of music)

Mr. WORTHINGTON: (As Sully) Okay, location, shack, and the days are starting to

blur together. The language is a pain, but you know, I figure it's like field-

stripping the weapons. It's repetition, repetition. Na'vi.

Unidentified Woman #2 (Actor): (As character) Na'vi.

Mr. WORTHINGTON: (As Sully) Na'vi.

Unidentified Woman #2: (As character) (Speaking foreign language).

Mr. WORTHINGTON: (As Sully) Neytiri calls me scoun(ph). It means moron.

GROSS: Jim Cameron, welcome to FRESH AIR. Can I ask you to give us an example

of a shot or two or a scene that epitomizes for you what you can do with 3-D

that you couldn't do in a regular film?

Mr. JAMES CAMERON (Filmmaker, "Avatar"): Well, I think it's sometimes as simple

as, you know, a shot in a snowstorm would feel so much more tactile to the

viewer. You'd actually feel like the snowflakes were falling on you and around

you, you know, that sort of thing, any time that the medium of the air between

you and the subject can be filled with something.

So we did a lot of stuff in "Avatar" with, you know, floating wood sprites and

little bits of stuff floating in the sunlight and so on, and rain and

foreground leaves and things like that. It's all a way of wrapping the audience

in the experience of the movie.

GROSS: And there's even a shot - and I think this looked deeper because of the

3-D, but you tell me - there's a shot in which the spaceship that's

transporting the people to Pandora, it's a shot of, like, a long, narrow bench,

basically, of seats, like a row of seats that the guys are sitting on. And I

think it looked particularly long because of the 3-D, or is that just me?

Mr. CAMERON: No, I think you're right. I think it's an enhanced sense of depth.

We get depth queuing in flat images all the time. We understand perspective,

you know, linear perspective, aerial perspective. When we see a human figure,

and that figure's very tiny, we don't â our brain immediately says that's not a

tiny guy, an inch tall, that's somebody very far away.

So all those depth queues are always there. When you add what 3-D does, 3-D

gives you parallax information. It actually gives you the difference between

what the left eye sees and what the right eye sees, and that creates even more

depth information.

So now all these different depth queues have to be correlated in the brain in

the space of a few microseconds when you first see the image. And I would

submit, although I haven't seen data on this, that the brain is more active.

The brain is more engaged in the processing of the images.

GROSS: So do you see in 3-D as you're shooting?

Mr. CAMERON: Well, I mean, we all see in 3-D all the time.

GROSS: But not through a lens.

Mr. CAMERON: Well, no, I mean, I can. I have a 3-D viewing station nearby, but

I typically don't use it because I've done â I've shot so much 3-D, I kind of

know what it's going to look like. So I don't slow down to check it. But you

know, I have somebody watching, and if there's something that I'm not aware of,

they'll let me know.

GROSS: Didn't you help develop, like, a special, new virtual camera?

Mr. CAMERON: Yeah, but that's a whole different deal. That has nothing...

GROSS: What is it?

Mr. CAMERON: That has nothing to do with 3-D. The virtual camera was a way of

interfacing with a CG world so that I could view my actors as their characters

when we were doing performance capture. So imagine, here's Zoe Saldana or Sam

Worthington in our capture space, which we called the volume, and when you look

at them, they're wearing kind of a black outfit, which is their capture suit,

but what I look at, and what I see in my virtual camera monitor is an image of

them as a 10-foot-tall, blue, alien creature with a tail.

GROSS: Wow, that's...

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. CAMERON: And it's in real time.

GROSS: That's kind of amazing.

Mr. CAMERON: Yeah, it's simultaneous.

GROSS: So there's, like, a computer, a CG computer in the camera that

transforms the image?

Mr. CAMERON: Yeah, more or less. The camera really is just a monitor and a set

of tracking markers, and it connects to a couple of computers, actually. The

first one takes in that tracking data and figures out where the camera is in

space relative to the actors, and then the second computer takes that

information about the characters and where they are and turns them â or the

actors and where they are and turns them into their characters and supplies the

setting.

So I would see Zoe and Sam as Neytiri and Jake in the jungle of Pandora, for

example, you know, fully lit image of the Pandoran rain forest. You know, it's

not the same as the final image of the movie in the sense that it's a much

lower resolution so it can render in real time.

GROSS: Let's talk about the characters a little bit.

Mr. CAMERON: Sure.

GROSS: Let me tell you one of the first things that strikes me about the

heroine. Now, in comics and in pulps, and I know you're big fans of those, the

women were always curvaceous and buxom and, of course, scantily clad.

Mr. CAMERON: Of course. That's a given.

GROSS: That's a given. Now, the heroine in "Avatar" is so skinny. I mean, all

the characters are. All of the characters in this imaginary moon, they're all

kind of elongated and very thin. So she's elongated and very thin with, like,

little breasts.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: And scantily clad.

Mr. CAMERON: Athletic breasts.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Oh.

Mr. CAMERON: Something that wouldn't be cumbersome when you're running through

the forest rapidly in pursuit of your prey.

GROSS: So I'm wondering about that decision because I think that must say

something. I'm not sure what it says, but I figure it must say something about

people's expectations of sexuality or athleticism now and, like, you know, a

female heroine and also what, I mean, a lot of action and fantasy films are

directed at young males, and young males usually want to see that full-figured,

buxom, you know.

Mr. CAMERON: Yeah, yeah. They don't...

GROSS: So talk to me a little bit about designing her and how that compares to,

like the female sci-fi comic heroines you grew up with.

Mr. CAMERON: Yeah, I mean, your typical comic heroine is, you know, is quite

voluptuous. And, you know, I think, you know, we were just looking for

something that was a little bit alien, you know, and so, you know, I use the

example of, you know, Giocometti sculpture, you know, where you have these kind

of vertically attenuated figures and then relating it back to some, you know,

tribal cultures in Africa like the Masai, you know, herders who were very, very

tall and lean and, you know, quite beautiful, and you could see they are

muscular, very clearly defined.

And you know, it was a way of having them be human and slightly pushed at the

same time. Because for me, the Na'vi always were about an expression of kind of

the better part of ourselves in the sense of them being, you know, kind of the

â almost the Rousseau model of the noble savage, untainted by civilization, all

that, which is a quite romantic idea, and not one I think is really true, by

the way, in the real world. But it made sense to me that in this film, you've

got this polarization where the humans actually represent an aspect of human

nature that is, you know, venal and corrupt and aggressive and so on.

And the Na'vi represent an aspect of human nature that is more aspirational for

us. They're more the way we would see ourselves or want to be. You know,

they're athletic, they're graceful, they're, you know, connected to their

environment and to each other and so on.

You know, so I didn't want to make them these fat waddlers, kind of crashing

through the bush. I wanted them to suggest a kind of antelope-like grace. And

so, you know, a big part of our creation of these characters was working with

movement people. We had a movement coach who was an ex-Cirque de Soleil

choreographer. We worked with our stunt team to create this very graceful and

powerful and athletic kind of, you know, complete body performance for the

characters, for the actors and for the stunt doubles.

GROSS: Now, you had to make up a language, also, I think with the help of a

linguist.

Mr. CAMERON: Yeah.

GROSS: What were you looking for in the language, and how do you put together a

kind of grammatically coherent language?

Mr. CAMERON: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. Well, that's where the linguist, Dr. Paul Frommer,

came in. And he was the head of the linguistics department at USC at the time,

and he did more than help. He actually created the language. Or more properly,

he created the translations of the lines that we needed for the script. I don't

think â he didn't create, like, a full language with a vocabulary of 20,000

words, but I think we now have a vocabulary of about 1,200 or 1,300 words.

And I actually had him on set with me so that if the actors wanted to

improvise, they could go over to him, and say how would I saw this, how would I

say that? Sometimes he had to create words right on the spot, but they had to

be words that were consistent with the kind of sound system that we were using

for the language.

And I guess I sort of set it in motion when I created character names and place

names and based them on some, you know, kind of Polynesian sounds and some

Indonesian sounds. And he riffed on that, and he brought in some African sounds

that were ejective consonants and things like that, kind of clicks and pops,

and he sprinkled those in. And he came up with a syntax and a typical sentence

structure, which I think has the verb at the end, kind of in the German

sentence structure, you know, I to the store go. It's noun, object, verb. So I

think that's how Na'vi is structured.

So it follows linguistic rules, and that's why it sounds correct. And all the

actors had to adhere to a standard of pronunciation so that it didn't sound

like everybody was making up their own gobbledygook, which I think over and a

two-and-a-half-hour movie you would have felt you were being had if we had done

it that way.

GROSS: So can you speak to me in the Na'vi language?

Mr. CAMERON: You know, I mean, I can only say lines that are in the film.

GROSS: Yeah, yeah, that's fine.

Mr. CAMERON: I can say, well: (Speaking foreign language). That means I see

you, my sister. No, I see you my brother.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. CAMERON: (Speaking foreign language) is I see you, my sister. Or (Speaking

foreign language) means I was going to kill him, but there was a sign from

Awha(ph).

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is James Cameron, and we'll talk

more about how he made "Avatar" after we take a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is James Cameron, and he wrote and directed "Avatar." He also

made "Titanic," "Terminator" and "True Lies," oh, and "Aliens," too. You know,

in one of your documentaries, one of your deep sea documentaries, you describe

underwater life as the most insane life forms ever discovered. So have you seen

any creatures, like real creatures, under the sea that helped inspire any of

the creatures in "Avatar"?

Mr. CAMERON: Well, absolutely. I mean, I think first of all, there's the sort

of generic answer, which is there's such an inspiration to be had from the, you

know, what I call nature's imagination because, you know, I surrounded myself

on "Avatar" with these really, really great creature-design artists. And every

time we thought we had come we had come up with a brand new idea, somebody

would come in with a photograph or a reference, and we realized that nature

beat us to it, you know, by probably 300 million years.

I mean, a specific â if you want a specific example...

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. CAMERON: ...if you recall when Jake goes into this kind of glade of these

kind of orange, flower-like structures, and he begins to touch them, and they

retract down into the ground, that's actually based on a small tubeworm, which

is kind of colloquially called the Christmas tree worm.

And, you know, divers can see them any time they dive in a coral reef

environment. They just look like these little parasols, and when you try to

touch one, it will retract into its tube.

So we just took that idea, took it out of scale to, you know, several hundred

times its real size and took it above water and put it in a forest glade. So

it's â you know, a lot of our so-called alien ideas in "Avatar" were really

just taking examples from nature and taking them out of context, out of scale

and, you know, out of where we would normally see them.

GROSS: "Avatar" combines a lot of different movie genres in its own way.

There's aspects of the Vietnam War movie, aspects of the Iraq War movie because

a lot of people think Iraq War is about oil, and...

Mr. CAMERON: Sure.

GROSS: ...the battle in your movie is about some kind of ore, some kind of

mineral that's very valuable.

This parallels to the Westerns, where, you know, like the white people come and

conquer the indigenous people, and there's parallels to, like, creature films

like "King Kong" where he battles other prehistoric creatures and, you know,

"Rodan vs. Godzilla" kind of film.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Were you thinking of all those genres?

Mr. CAMERON: Now you're getting out on â you're getting out on a limb now.

GROSS: No, I don't know.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. CAMERON: Well, you know, look, the Vietnam stuff and the Iraq stuff is

there by design, and the references to the colonial period are there by design,

the way in which, you know, European civilization flowed outward and sort of,

you know, took over and displaced the indigenous people in North America, South

America, Australia - pretty much everywhere they went, you know.

And, you know, so I think it's â at a very, very high level, at a general, at a

very generalized level, it's saying our attitude about indigenous people and

our sort of entitlement to what is rightfully theirs but our sense of

entitlement is the same sense of entitlement that causes us to bulldoze a

forest and not blink an eye.

You know, it's a â it's just human nature that if we can take it, we will, and

sometimes we do it in a very, you know, just naked and imperialistic way, and

other times we do it in, you know, very sophisticated ways with lots of

rationalization, but it's basically the same thing. It's a sense of

entitlement. And we can't just go on in this kind of unsustainable way, just

taking what we want and not giving back.

GROSS: The main character, the main male character in your movie, is a Marine

who lost the use of his legs in war, but by becoming an avatar, he gets to live

a parallel life...

Mr. CAMERON: Right.

GROSS: ...through his avatar. And his avatar has these incredible physical

adventures, beautiful physical adventures.

Mr. CAMERON: Right.

GROSS: And I read that your brother is, or was, a Marine.

Mr. CAMERON: Yeah, well, you're never an ex-Marine. You know, once you're a

Marine...

GROSS: Right, right.

Mr. CAMERON: ...you're always a Marine, even if you're out of the Marine Corps.

You know, he was in â he fought in Desert Storm in '91, and you know, he's

regaled me with tales of the Marine Corps, and you know, I have a number of

guys that work for me that were, you know, his squad mates or other Marines

that he met, you know, in his travels.

And I have a great deal of respect for these guys. I really personally believe

in their world view, which is one of a sense of being able to overcome any

obstacle. They have a great sense of duty. They want to have a mission.

And I thought: How cool would it be to have a main character in a science

fiction movie who was a Marine? And so I just played that idea out. You know,

that was on my mind. You know, Desert Storm was in '91. I was writing this in

'95.

And I think that's â and one thing that has struck me recently because there's

been so much chat, kind of, around this movie, is that there's been almost zero

dialogue about the fact that you have a major action movie where the main

character is disabled, which I think is actually unprecedented. And yet

nobody's said anything about that. I think it's kind of strange, to tell you

the truth.

GROSS: Well, the main character's, like, 50 percent disabled because he's

disabled as himself. As his avatar, he does things that no human could even do.

But that leads me to something I think is pretty interesting about the film,

which is that he's literally disabled, but we're all limited by the things we

can do and the things we can't do. And we all, in our lives, have dreamed about

flying and have dreamed about doing things that we can't do, either because of

the laws of nature or because of our own physical limitations.

Mr. CAMERON: That's great. You're on to something here.

GROSS: Yeah, so you have given him this kind of dream-like life that is very

real for him in which he can do all the things that he's limited from doing in

the real world.

Mr. CAMERON: Right, right, right.

GROSS: And it seems like you might feel similar things yourself, you know,

like, have that kind of dream life.

Mr. CAMERON: Well, yeah. Your imagination, you know, is â you know, there's

always that huge gap or shortfall between what you could imagine and what you

can actually do. And I think that we go from a state as children where we don't

know what we can't do, and we don't know what's not possible, and kids actually

probably sort of think they can fly.

You fly in your dreams as a child, and you tend not to fly in your dreams as an

adult, and this is an almost universal experience. So, you know, in the avatar

state, when Jake is in his avatar state, he's getting to return to that almost

childlike dream state of doing amazing things.

And so it's speaking, in a sense, to this â the way people, you know, are going

into various types of avatar states, living vicariously, whether it's through

video games or through movies and so on.

So in a funny way, it's actually kind of a comment on the way we find

expression for our imagination and, by the way, a little bit even of a

cautionary comment because Jake allows his body to physically degrade

throughout the movie as he invests more and more of his time and energy and his

soul in the, you know, in the avatar world, you know, almost to the point

where, you know, he loses all strength and all interest in his true human form.

GROSS: Do you have an active dream life?

Mr. CAMERON: Very much so, and that's probably really the heart of your first

question. A lot of the imagery in "Avatar" comes from dreams that I've had over

time. I can remember distinctly having a dream in college of a glowing,

bioluminescent forest and getting up and very quickly sketching it with oil

pastels, trying to get the colors down, trying to get, you know, what I had

imagined in the dream down on paper and feeling this great sense that I hadn't

succeeded. It just was this ugly thing. It wasn't what I had seen in the dream.

So, you know, part of â I think that's part of what drives a lot of artists is

dream imagery and the kind of subconscious associations that happen in dreams.

I know the surrealist artists strongly believed that their mission was to

translate to the canvas images they'd had in dreams without any attempt to

analyze or mediate them and that that was kind of their ethos, and I kind of

adopted a little bit of that when I was making "Avatar." I thought, you know,

if I like an image, I'm going to put it in the movie, and Iâm not going to try

to justify it.

So, you know, you see floating mountains in the film. They're never explained.

Now, I happened to have, you know, sort of reverse-engineered a scientific

explanation of how those mountains float, but every time I tried to shoehorn it

into the movie, I just found that it was unnecessary explanation. People would

accept that they had been transported to this amazing place where the rules

were different, and it was okay for mountains to float. And it turned out that

that technical explanation was completely unnecessary.

GROSS: James Cameron will be back in the second half of the show. He wrote and

directed "Avatar" and "Titanic." I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

xxx

(Soundbite of music)

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. Iâm Terry Gross back with James Cameron. He wrote and

directed "Avatar," which is nominated for nine Oscars. He also made the films

"Titanic," "Alien," "True Lies," and "Terminator."

So you are now probably most famous for your biggest films, "Titanic" and

"Avatar," both of which have a lot of special effects and feats in them. But

you started off helping to make Roger Corman's films.

Mr. CAMERON: Mm-hmm. Right.

GROSS: Movies like "Battle Beyond the Stars," "Galaxy of Terror." And Corman is

famous for, in his early career, making these like, real low budget, quickie...

Mr. CAMERON: Cheap.

GROSS: Yeah. Yeah, you know, action films and...

Mr. CAMERON: Yeah. He's famous for being cheap.

GROSS: Yeah. So, what did you learn from the real cheap side of special

effects...

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: ...that you later applied to the real expensive side of special effects?

Mr. CAMERON: It's a funny question, because I was just talking to Roger last

night and I haven't seen him in years, but we ran into each other and we were

joking about the fact that he's made probably all of his movies combined would

not have cost as much as "Avatar" and he's made, you know, 100 films. But, you

know, we were having a good laugh about that. But yeah, there are lessons that

one learns in those early kind of guerrilla filmmaking days that stay with you

the whole time.

And, you know, and what you learn in those early films, is just that your will

is the only thing that makes the difference in getting the job done - one's

will. And it teaches you to improvise and in a funny way to never lose hope,

because youâre making a movie and the movie can be what you want it to be. It's

not in control of you. Youâre in control of it, you know, so theyâre a lot of

lessons that are more really character lessons.

GROSS: So can you share your favorite cheap special effect that you were

involved with from a Corman film?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. CAMERON: Well, they were all cheap. You know, I mean we used to love - we

actually were fairly sophisticated even for that time. We were doing motion

control and fairly complicated optical special effects and so on for Roger.

But, of course, the ones we liked the best were the biggest cheats, where we'd

glue a model to a piece of glass and stick it in the foreground and pretend it

was far, you know, far away and really big and have all the actors turn away

from the camera and point at it even though it was sitting right in front of

the camera, and it actually created a compelling illusion, you know, foreground

miniature. It's a lot of fun. And it's the ones where you really think youâre

get, you know, youâre pulling something over on the audience that were the most

fun.

GROSS: Now, you know, in "Titanic" there were so many like, water-rushing-in

kind of effects when the ship was sinking.

Mr. CAMERON: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: And I know you grew up not far from Niagara Falls. Is that right?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. CAMERON: Right. Yeah.

GROSS: So is it stretching too much to think that the power of the water of

Niagara Falls had some kind of influence on you?

Mr. CAMERON: Well, you know, I mean I grew up within the sound of Niagara

Falls. I lived, you know, with that constant rumble in the background, so I

certainly always had a respect for the power and the force of water. And then

in the filmmaking, starting with "The Abyss," I saw how, you know, you can dump

a dump tank with 10,000 gallons in it and have it destroy your set. I mean

literally rip it apart. And so, overtime, I've learned to really, really

respect that force of water from an engineering standpoint. And I'm very

rigorous when I work with water, that my, that, you know, my special effects

guys and my set construction people, someone really understand what they're

dealing with. Because generally speaking, they underestimate the force and

energy of water by a factor of 10.

GROSS: When you say that this thing of water ripped apart your set, you mean

accidentally, right?

Mr. CAMERON: Accidentally, yeah. The...

GROSS: What happened?

Mr. CAMERON: Well, it blew the wall right out. You know, we were doing a

flooding scene and it hadn't been properly strong-backed. And, you know, no one

was hurt but, you know, it really makes you realize what youâre dealing with.

So on "Titanic" we had a lot of water stunts and, you know, I would, you know,

constantly, you know, walk the set, look at how it was rigged and so on, and

I'd want to see the engineering. I'd want to see the numbers. I want to see how

they had calculated everything to make sure that there was a safety margin.

GROSS: Okay. James Cameron, years before Governor Schwarzenegger was governor,

he was...

Mr. CAMERON: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: ...your cyborg in "Terminator."

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: So I'm sure youâve told this many times but...

Mr. CAMERON: I'm not sure who was working for who that time.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: I'm sure youâve told the story many times but tell us how and why you

cast him.

Mr. CAMERON: Well, you know, I actually had this kind of flash, that Arnold had

this amazing face. I wasnât, I mean his physique was fine, made sense that we

could hide this kind of infernal machine inside that, you know, inside his size

of his physique, but it was really his face that was interesting to me. And,

you know, someone suggested that he play the character played by Michael Biehn

and that didnât make much sense to me. But I wound up going to lunch with him

and we had this great time talking about the movie and just life in general. I

found him to be incredibly charming and intelligent, and that was really the

beginning of a friendship. And so I went back to the executive producer of the

film and said, you know, he's not going to work as Reese, but he'd make a great

terminator and we offered him the part that day and that's how the movie got

made.

GROSS: So what was your reaction when years later he ran for governor?

Mr. CAMERON: Oh, it didnât surprise me at all. Arnold...

GROSS: Why didnât it surprise you?

Mr. CAMERON: Well, he'd always been very politically aware and, you know, he's

a natural leader. He just, he exudes the charisma and the intelligence and the

focus and the discipline of a leader, and he's always been that way. And in a

way, you know, he was kind of working under his weight classes as a Hollywood

movie star because it didnât use all his talents. And so when he decided to run

for office, there was zero surprise in that. And there was zero surprise when

he won.

GROSS: This is nobody's business but yours, but I'll ask it anyways and you

could tell me you donât want to answer it; did you vote for him?

Mr. CAMERON: I'm Canadian. I can't vote.

GROSS: Oh, off the hook.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. CAMERON: Off the hook. But I would have. Even though my, you know, my party

affiliation would be Democrat if I could vote here, I would've voted for Arnold

because I believe in the man.

GROSS: Now, Charlton Heston was in one of your movies "True Lies," which...

Mr. CAMERON: Mm-hmm.

GROSS: ...starred a more charming version of Arnold Schwarzenegger. He's like

a...

Mr. CAMERON: Oh sure.

GROSS: ...a secret spy in it and even his wife doesnât know he's a spy and he's

very charming and elegant in that side of his life.

Mr. CAMERON: Right. Right.

GROSS: And very tough and brutal on the other side of his life. Charlton Heston

has a small part in it.

Mr. CAMERON: Yeah.

GROSS: And it must've been interesting to direct him. I mean he was among other

things, Moses in the movies. I'm sure your politics are very different from

him.

Mr. CAMERON: Oh yeah, very different. But I found him charming and really

humble before the craft of acting in the old school way. He came in, he said,

just call me Chuck. Donât let the fact that I'm an icon, you know, affect you.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. CAMERON: And...

GROSS: He said, modestly.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. CAMERON: He said modestly. And then he sat in a chair and he never left the

set all day long. He came in for off camera, you know, to do his side of the

scene for off camera, which, you know, certainly a star of his stature wouldnât

need to do. And he never left the set. He just sat there and read. And you

could just see that it was a life of, there were patterns formed by a life of

dedication to the craft, and I really respected that. And, you know, I felt I

had to really be on my game that day and be 100 percent professional as a

director. Because, you know, he came from the studio system where, you know,

you shot X number of pages a day, boom, boom, boom, and everybody knew their

tasks and, you know, it was a lot of fun working with him.

GROSS: Now, you didnât expect to go into movies. So what was your break that

led you through the door?

Mr. CAMERON: Well, I think you make your own luck, you know, and it wasnât

really a break. I had started - I'd sort of quit my job. I was working as a

truck driver. I quit my job. I started making little films, you know, used up

all my savings and somehow a little effects film that I had made got the

attention of somebody who was working for Corman on "Battle Beyond the Stars"

and I wound up getting an interview and coming into the model department and

sort of clawing my way up through the system, pretty rapidly, which you could

do in that kind of environment because it was so kind of ad hoc and nobody

really knew what they were doing anyway. So, you know, I mean you get the door

open a crack, and then you, you know, you just keep wedging your way through

the door. That's how you work it.

GROSS: So what movie have you seen more times than any other film?

Mr. CAMERON: Oh, I donât know. I mean I saw "2001: A Space Odyssey" 18 times in

the first two years of its release, and that was before VHS or DVD, where you

actually had to go to a movie theater. You know, I've seen, you know, "Wizard

of Oz," which is my favorite film, many, many times.

GROSS: What kept you going back for "2001?"

Mr. CAMERON: Initially I was fascinated by the ideas and by the majesty of it.

You know, I was a big science fiction fan and, you know, I was really trying to

figure the movie out, and then later it was more about trying to figure out how

it was done.

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. CAMERON: And that was really the transition point for me from essentially

being a fan to being a practitioner because then I'd get a small camera and I

made some space models and I learned how to light them, and pretty soon I was,

you know, I was making shots. So, you know, I didnât call myself a director at

that point, but I had definitely made the transition to wanting to be a

filmmaker.

GROSS: Well, one more question: a lot of people have noted that your film is up

against "The Hurt Locker" for an Oscar.

Mr. CAMERON: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm.

GROSS: And "The Hurt Locker" was directed by Kathryn Bigelow who you were once

married to. And I think she gave you a copy of the screenplay to look at even

though you had long separated...

Mr. CAMERON: Yeah, yeah.

GROSS: ...because she wanted your opinion on it. So this is like a big media

story that, you know, ex-spouses up against each other at Oscar. So what does

that mean to you?

Mr. CAMERON: Well, I think it completely trivializes our relationship to reduce

us to exes. You know, we were married for almost two years 20 years ago and

since then weâve been colleagues and collaborators and close friends for 20

years. And I've produced two of her films and, you know, I've always sort of,

you know, steadfastly promoted her career as a director, you know, when I was

actually acting as her producer and subsequently, not that she in recent years

has really needed any help. She's, you know, definitely been well-established

and the accolades that she's getting now, you know, in this awards season and

the critical recognition and so on is for one, way overdue. For two, itâs such

a great celebration of her accomplishments as a filmmaker that, you know, I'm

the first one to cheer when she wins an award. For me itâs a win-win situation.

GROSS: Thank you so much for talking with us. Itâs really been fun and

interesting. Thank you.

Mr. CAMERON: Thanks.

GROSS: James Cameron wrote and directed "Avatar" which is nominated for nine

Oscars, including Best Director.

You can find links to FRESH AIR interviews with each of the five Best Director

nominees on our Web site, freshair.npr.org.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

123810319

*** TRANSCRIPTION COMPANY BOUNDARY ***

..DATE:

20100218

..PGRM:

Fresh Air

..TIME:

12:00-13:00 PM

..NIEL:

N/A

..NTWK:

NPR

..SGMT:

Adam Shankman's Winning Job: Producing The Oscars

GROSS, host:

With just a little more than two weeks to go before the Oscars, Adam Shankman

is a little stressed out. He's co-producing the Oscar telecast with Bill

Mechanic and neither of them has ever done this before. Mechanic and Shankman

are making some changes this year. We asked Shankman to talk about what they're

up to. He directed "Bringing Down the House," and the movie musical remake of

John Waters' film "Hairspray." He's also a choreographer who got his start

dancing in and choreographing for music videos. He's a judge on the TV show "So

You Think You Can Dance."

Adam Shankman, welcome back to FRESH AIR. So the official Oscar poster says

"You've never seen Oscar like this." So what - give us an example of something

youâre trying to do different from how itâs been done.

Mr. ADAM SHANKMAN (Film director, producer, dancer, actor and choreographer):

Well, the most obvious two things are that they're 10 nominees in the Best

Picture category and the morning of the nominations Bill and I were basically

dancing a jig because the nominees represented a true cross section of, you

know, the movie lovers taste. And, you know, to go from "Hurt Locker" and

"Education" all the way to "Avatar" and "Blindside" to "District 9," I mean it

just represents everybody. And so that's really, really thrilling and how we're

handling that is very smooth and elegantly and hopefully in a way that makes

people want to go out and see the movies whether they win or not. And then the

other obvious thing...

GROSS: Is that why it's 10 nominees now, so that there's more depth for...

Mr. SHANKMAN: Opportunities.

GROSS: ...for movies to...

Mr. SHANKMAN: More opportunities for popular movies to come out.

GROSS: ...to be able to say nominated for Oscar.

Mr. SHANKMAN: Well, itâs not to be nominated for an Oscar, it's to say come

watch the show because the movie youâve is on it. You know, "Avatar" really

kicked that up, because everybody's seen "Avatar" so there's a real footrace

there. There's actually footrace between a couple in some of the categories

which, you know, itâs really hard these days because there's so many award

shows that come before the Oscars they kind of cannibalize the Oscars, and I

think, the special ness of the Oscars.

GROSS: Yeah, the way they all say, well, we predict who the Oscar winner's

going to be.

Mr. SHANKMAN: Yeah. I mean...

GROSS: So how is that affecting what you want to do, given that they're - weâve

already seen a lot of these people accept their awards and wear their best

costumes and yeah.

Mr. SHANKMAN: That's how it affects it is that some actors say like, you know

what? I'm overexposed. I donât need to do the show. I donât want to do the show

because I've been to the Golden Globes and the Grammies and the SAG Awards and

the Haiti tribute and, you know, so they just donât want to come on the show if

they're not actually nominated, and it's horrible because that means they're

not being part of their industry. It's the Super Bowl of the year.

GROSS: So when you say they donât want to be on the show, you mean as

presenters?

Mr. SHANKMAN: Yeah, as presenters. Yeah, as presenters. We have a few key

players not in place right now. But we have our desired list. We have - but

there's a few key ones missing. We have almost everybody.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. SHANKMAN: We have almost everybody.

GROSS: Now, how did you choose Alec Baldwin and Steve Martin to host? They co-

star in "It's Complicated."

Mr. SHANKMAN: What happened was Bill Mechanic and I met, had lunch, and we very

much - we first had a pretty radical idea about who we wanted to host the show,

which the Academy swatted down because it was too big a wildcard.

GROSS: Youâre not going to tell me who that was, right?

Mr. SHANKMAN: You know what? I actually am going to tell you, it was Sashay

Baron Cohen.

GROSS: Oh no. Oh wow.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SHANKMAN: And they thought it was too big a wildcard. They thought it

was...

GROSS: Oh, that would've...

Mr. SHANKMAN: ...just too unpredictable.

GROSS: Oh, what a good reason to watch.

Mr. SHANKMAN: Hello, that's my thing. I mean, you know, once you get hired to

do the show, we donât control the nominations, we donât control the winners,

but we control, you know, everything around all of that stuff, and our job is

to put on the best show possible and really give the audience - not just the

people in the room, but the viewing audience, the people who pay our bills, you

know, a great, great evening. And so I loved the idea.

GROSS: Yeah, if you had Sashay Baron Cohen hosting, you donât even know who'd

be hosting because he might do it as one of his characters and...

Mr. SHANKMAN: I know. I mean it would be, it would just be spectacular. But I

think the Academy felt like not only is it unpredictable but it could

overshadow the nominees. Anyway, so anyway then we immediately went to this

idea of co-host. And the very cool thing about the co-host thing is that we

didnât realize there haven't been co-hosts in this fashion since 1928, which

was the first year of the show. And so that's another way that itâs going to be

very, very different because they're going to share the duties, their comedy is

going to be very, very snappy. We both - we all love the way that Neil Patrick

Harris did the Emmys, how he really kept them moving along, and Alec and Steve

are going to be - and they're doing a lot of that stuff too.

But what the great thing was, was by having Steve, it anchors it in kind of a

tradition and he is one of the most beloved hosts of the show theyâve ever had.

And then we thought Alec made a great comic wildcard, and they bring out the

funniest versions of themselves with each other. The chemistry between them is

so magical. When I say it's like Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, I'm not kidding.

GROSS: Are they going to sing?

Mr. SHANKMAN: I'm not going to tell you that.

GROSS: Aw.

Mr. SHANKMAN: That would ruin the surprise.

GROSS: So tell me one thing...

Mr. SHANKMAN: Chipmunk.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Thatâs our safe word.

Mr. SHANKMAN: That's our safe word when she starts going into territory that

I'm not going to talk about - chipmunk.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: So last year there were former winners of Oscars who presented - who

read the names of the nominees...

Mr. SHANKMAN: Yeah. Yeah.

GROSS: ...and presented the Oscar.

Mr. SHANKMAN: Yeah.

GROSS: So youâre doing that again this year, right?

Mr. SHANKMAN: We loved the idea. We're doing something a little bit different

with it, but in point of fact, something like that is going to be done and it

has to do - the way we're doing it has to do with a bit more of

interconnectivity because what was really, really stunning about last year the

way they did that was the video clip build-up to the reveal of the stars, I

mean the editing of that stuff was so breathtaking and so big that when those

screens went up and you saw the five walk out, youâre just like going, whoa, my

God, it was so dramatic and beautiful. And then in many cases the presenter

then started talking about the person they were nominating and they clearly

didnât know who they were, basically.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SHANKMAN: They were, you know, there was very little connectivity in there,

and I think that was because it was a great idea on Bill Condon and Larry

Mark's part that it sounds like it took - like it didnât kick into high gear

until later and I think it was hard getting people to do it, actually. So we

are taking the idea and playing with that.

GROSS: All right. And youâre not going to tell how.

Mr. SHANKMAN: Yeah.

GROSS: But that's okay. I'll be watching.

Mr. SHANKMAN: No, no, no, that's fine. I mean just know that it will be sort of

maybe not as dramatic but definitely a little more emotional.

GROSS: My guest is Adam Shankman. He's co-producing the Oscar telecast on March

7th. We'll talk more after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: My guest is Adam Shankman and he is one of the producers of the Academy

Awards, which will be broadcast March 7th.

I donât know if you feel comfortable answering this, but since we're talking

about award shows - I wonder what you thought of the Grammies.

Mr. SHANKMAN: I - okay, I thought that it was a very interesting try at a

business that has been so ravaged because, you know, basically I mean it was -

what was so incredibly weird was they had on an almost four hours show, it felt

like, where they did 22 performances and gave out like eight or nine awards.

And, you know, every time a person would come up or they'd introduce a person,

they say earlier today so-and-so won seven Grammies.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SHANKMAN: And you know, but it was serious, but their ratings went up 35

percent. So you know, they were onto something with that. I personally felt

they frontloaded some of the best acts too early into the show and then some of

the less energetic acts were a little too late in the show. Like, they didnât

pace it right for me, personally. Sorry, Grammy people. But that's just my take

on it. But I mean that is truly a reaction to an industry that has been

devastated. I think that's what happened on that show.

GROSS: Can I ask you something? I know youâre a choreographer and director and

producer and not a costume designer, but I think...

Mr. SHANKMAN: Yeah.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: I think you still have an opinion on this.

Mr. SHANKMAN: Yeah.

GROSS: I feel like I'm so tired of seeing dancers in S&M fetish wear, maybe

especially...

Mr. SHANKMAN: Yeah. I think once again, that's a reaction - that comes from the

old school video world of, you know, this is what is sexy - how do you show

sexy without being overt? And you know, I think a lot of people just go

straight for overt and obvious because it's the easiest place to go. You know,

itâs not particularly creative - and you know, it's funny because a lot of

times you'll see them dressed like that when they are singing even if it's like

a song about a breakup. It's sort of strange. It's sort of like there's nothing

in there that says like anything about lifestyle being that like crazy vinyl

look, you know? But it is a very easy place for people to go to be overtly sexy

and so I think that's why it happens.

GROSS: So since youâre going to be backstage, do you have to worry about what

to wear or...

Mr. SHANKMAN: Oh my God. I'm so excited about what I'm wearing. You have no

idea. Are you kidding?

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SHANKMAN: I am wearing the most beautiful - Tom Ford is making me...

GROSS: No. Oh no.

Mr. SHANKMAN: Yes. I can't believe it. It's - like, I saw it, I did my fitting

and basically started to weep. It was like a clothing orgasm.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SHANKMAN: It was unbelievable, it was so beautiful. So I'm very excited

about what I'm going to be wearing. Because then, you know, afterwards we have

to go to the Governors Ball and do our thing and either hang our heads in

shame and leave in a stretcher or walk around like, you know, with our arms up

like "Invites."

GROSS: So do you want to describe what he made you?

Mr. SHANKMAN: What he made me? The tux?

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. SHANKMAN: Oh, it's so cool. It's like kind of from "Casino." Itâs a little

bit more of like a, the jacket, it's like this beautiful fabric. I feel so like

superficial, but whatever, with these beautiful silver threaded gold circles in

it in the tux jacket and with this perfect fit. It's like cut to make me look

like a superhero, basically.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SHANKMAN: And then a shirt that basically was made by blind angels, itâs so

beautiful. The fabric is so brilliant. This big beautiful puffy black bowtie

with a low cut black vest that has kind of rooting(ph), if you know what that

is, the way...

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. SHANKMAN: ...the texture of it, and then just, you know, gorgeous pants and

gorgeous shoes and gorgeous everything, and I, you know, basically I'm going to

put it in a glass case when I'm done. Or you know what? That's going to be my

version of a wedding dress.

(Soundbite of laughter)

Mr. SHANKMAN: You know, put it in a box and never to be touched again except on

sad moments when I'm playing "All By Myself" by Eric Carmen and Iâll just open

it up and, you know, look at it.

GROSS: So one last question: now youâre producing the Oscars and 20 years ago

you performed in the production of the...

Mr. SHANKMAN: (Singing) "Under the Sea."

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Yes, in "Under the Sea."

Mr. SHANKMAN: And the costume number. I was Baron Munchausen's in the costume

number. Yeah, there's no dignity.

GROSS: So whatâs the difference in how it looks watching from home on

television...

Mr. SHANKMAN: Itâs so sexy.

GROSS: ...versus the being there on stage?

Mr. SHANKMAN: Its vibe is kind of actually gorgeous mid-century and itâs just,

itâs sexy. There's screens everywhere and, you know, being in the room - well,

first of all, being in the room, itâs very hot and itâs not particularly

comfortable and, you know, there's camera equipment all over the place and

youâre there and youâre just watching. It's like going to a big Broadway show,

you know, with a gigantic stage and then - but being on the stage and looking

out, basically you see in the first 10 rows every movie star who's ever

breathed, you know, it feels like, and youâre close enough to touch Merlyn

Strep.

So for these - I mean it's crazy, you know? But I think for the - I think it's

actually nicer for the TV audience because it's just more comfortable. And

there's also all these great games that youâre going to be able to play this

year because weâve done so much work to create like inter-connective tissue

between the presenter and, you know, the nominee or the winner or the tribute

that I think it will be fun for people to try to guess how the things are

connected. There's a bit of a six degrees kind of a thing that we're doing.

GROSS: Well, thank you, Adam Shankman. Thanks so much for talking with us. Good

luck. Good luck with the ceremony and the broadcast.

Mr. SHANKMAN: Thank you. I need it. I need it. Cross your fingers and watch.

Watch it. You know, watch for either the train wreck or for the fabulousness.

That's what I'm thinking, you know.

(Soundbite of laughter)

GROSS: Adam Shankman is the co-producer of this year's Oscar telecast. He also

directed the movies "Bringing Down the House" and the musical version of

"Hairspray," and he's a judge on "So You Think You Can Dance." The Oscar

ceremony is March 7th.

You can find links to interviews with all five of the Best Director nominees on

our Web site, freshair.npr.org, where you can also download podcasts of our

show. And you can find more information about our guests by following us on

Twitter and finding us on Facebook at nprfreshair.

..COST:

$00.00

..INDX:

123844321

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.