Remembering Edward Gorey.

Macabre cartoonist and illustrator Edward Gorey died on Saturday at the age of 75 of a heart attack. His illustrations are the opening credits of the PBS show "Mystery." He wrote over 100 books including “The Gashlycrumb Tinies” an alphabet book which began “A is for Amy who fell down the stairs.” One of his other books “The Doubtful Guest” was a classic, about a creature who shows up uninvited at a dreary mansion and becomes a member of the family. Toward the end of his life, GOREY lived in a 200 year old house in Cape Cod, with his five or six cats. (REBROADCAST from 4/2/92)

Other segments from the episode on April 17, 2000

Transcript

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: APRIL 17, 2000

Time: 12:00

Tran: 041701np.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: Edward Norton Discusses `Keeping the Faith'

Sect: Entertainment

Time: 12:06

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: From WHYY in Philadelphia, I'm Terry Gross with FRESH AIR.

On today's FRESH AIR, actor Edward Norton. He directed and stars in the new romantic comedy, "Keeping the Faith." We'll talk about his new film and his earlier roles as a murderer with a dual personality in "Primal Fear," a skinhead in "American History X," and a wimp-turned-fighter in "Fight Club." And we'll hear about making his unexpected singing debut in Woody Allen's "Everyone Says I Love You."

Also, we remember the illustrator and author Edward Gorey. He died Saturday at the age of 75. Gorey's macabre yet witty illustrations graced many books, as well as the opening credits of the PBS series "Mystery."

That's all coming up on FRESH AIR.

First, the news.

(BREAK)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

My guest, Edward Norton, had no trouble getting noticed after he started making movies. He was nominated for an Academy Award for his feature film debut in "Primal Fear," in which he played an altar boy on trial for murder. Then Woody Allen cast him in his musical "Everyone Says I Love You." Norton played Larry Flynt's lawyer in "The People Versus Larry Flynt," and received another Academy Award nomination for his role as a skinhead in "American History X."

His movie "Fight Club," in which he co-starred with Brad Pitt, is coming out on video later this month.

Norton is now starring in the romantic comedy "Keeping the Faith," which he also directed. He plays a young priest whose best friend since childhood is now a rabbi, played by Ben Stiller. They're knocked off course when their old childhood friend, Anna Riley, played by Jenna Elfman, comes to town, and they each fall in love with her.

It's a problem for the priest, for obvious reasons, and a problem for the rabbi because she's not Jewish. This is a scene from early in the film.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, "KEEPING THE FAITH")

EDWARD NORTON, ACTOR: Oh, hey, speaking of (inaudible), I forgot to tell you something.

BEN STILLER, ACTOR: What?

NORTON: This is big. Guess who called me?

STILLER: Who?

NORTON: OK. Think about, who is the coolest woman you and I have ever known, ever?

STILLER: That's easy. Anna Riley, eighth grade, no question.

NORTON: You got it.

STILLER: What? She called you?

NORTON: Yes.

STILLER: Anna Riley called you?

NORTON: Yes, totally out of the blue.

STILLER: Why?

NORTON: Because she's coming to New York for work, and she wanted to get together with us. She just looked me up.

STILLER: Really?

NORTON: Yes.

STILLER: Anna Riley. What is she doing now?

NORTON: She's, like, analyzing synergies or synergizing analogies or some such thing. I couldn't follow it. She's, like, this very high-powered business -- you know...

STILLER: Woman?

NORTON: Woman, yes, thank you.

STILLER: Wow. And you told her about us?

NORTON: Yes, she flipped. In a good way. You know, I mean, she laughed for about 10 minutes, but she was excited.

STILLER: Man! That is so cool!

NORTON: I know.

STILLER: Wonder why she called you?

(END AUDIO CLIP)

GROSS: Edward Norton, welcome to FRESH AIR.

EDWARD NORTON, "KEEPING THE FAITH": Thank you.

GROSS: How did you end up directing and making this movie? How did you first find out about it?

NORTON: Well, it was -- it actually began with a script that a close friend and collaborator of mine wrote. His name is Stuart Blumberg, and we've known each other since college, and were roommates together in New York, and writing partners, wrote a lot of theater and some television episodes and screenplays and stuff like that. And over the years, he's been one of my closest kind of creative collaborators. And he wrote this in -- about three years ago, the original script for "Keeping the Faith," and gave it to me.

And initially, it was just a process of the two of us kind of rewriting it together and editing it, and then producing it, really. And it wasn't until about a year down the road, with -- in terms of developing it as a script with the studio that we finally decided we didn't really want to give it to somebody else, because we were -- you know, we didn't know if they would get our jokes.

So we just decided to do it ourselves, and that was really what led me into it.

GROSS: Now, in "Keeping the Faith," you play a young priest who isn't very physical or athletic. I mean, there are some funny scenes, for instance, on the basketball court where, you know, you're just not very good at it. Do you -- have you in your career gone from pumping yourself up to un-pumping yourself up? Like, in "American History X," you had to really, you know, put on the muscles. And then, you know, you've since had roles that were less physical. Even in "Fight Club," at first you're pretty physically unfit.

So how do you lose the muscles that you've gained?

NORTON: Well, I gained so much -- I mean, I put on so much sort of bulk for "American History X" that that wasn't really my natural size, and so when it was over, I -- and I did films like "Fight Club." I -- "Fight Club" was challenging, because I got so thin that I weighed less than I weighed in high school, so I was -- that was -- that was actually in some ways more difficult. But...

GROSS: Because you couldn't eat.

NORTON: Yes, no, I was fasting for months. And, you know, really, really trying to keep myself kind of emaciated so that I would have that kind of hollowed-out, sickly look for "Fight Club."

But "Keeping the Faith," I'm sort of back to my, you know, my comfortable middle ground.

GROSS: You know, it seems to me actors in other decades didn't have to either work out or stop eating or overeat as much as actors did -- today do to change their body for roles.

NORTON: Yes, I still think -- I think it's still a relatively infrequent demand of the job. I don't think it's -- I think there's been since the sort of advent of the character actor as leading actor in the late '60s and early '70s, you know, when you had a generation of actors, film actors like Dustin Hoffman and Robert DeNiro and Gene Hackman and Robert Duvall and Morgan Freeman, you have -- you had a lot of people coming along who were not your kind of classic Hollywood leading men. They were, in a lot of ways, character actors.

And you, as a result, you know, you started having actors who were more focused on sort of morphing into distinct characters than kind of playing a consistent persona, which was more the trend up until then. And I think as a result, you had people straying further afield from in some ways who they really were. And I think I sit more squarely in that tradition.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Edward Norton, and he directed and stars in the new movie "Keeping the Faith," which is a comedy about a rabbi, a priest, and the woman they're both in love with.

Let me ask you about your first movie role, which was "Primal Fear." In fact, let me play a clip from it. In this, you play a former altar boy named Aaron who's from a small town in Kentucky. You're accused of brutally murdering a cardinal. Your lawyer is played by Richard Gere. And you claim to suffer from amnesiac blackouts. And a psychiatrist hired by your lawyer thinks that that's a symptom of multiple personality disorder.

In this scene, after your lawyer tells you that he thinks you're really guilty, your other personality, Roy, comes to the surface. This is the first time your lawyer has seen evidence of a split personality.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, "PRIMAL FEAR")

NORTON: You're a lawyer. You're a lawyer, ain't you?

RICHARD GERE, ACTOR: Yes.

NORTON: Yes, with your fancy (inaudible) -- I heard about you. Well, my, my. You sure (bleep)ed this one up, counselor. It sounds to me like they're going to shoot old Aaron so full of poison, it's gonna come out his eyes.

GERE: Where is Aaron?

NORTON: He's probably off in some corner somewhere. You scared him off. You gotta deal with me now, boy. I oughta give you a beating on principle. Look at me. You ever come in here pulling that tough guy (bleep) on there again, I will kick your (beep)ing ass to Sunday. You understand me?

GERE: I understand you. I understand you. Aaron gets in trouble, he calls you. You're (inaudible).

NORTON: Aaron couldn't kick his own ass. Man, you saying with (ph) the duh-duh-duh (ph). Jesus Christ, he can't handle anything. (inaudible) sure he (bleep)ing couldn't handle all that preacher's blood, could he? You'd think (ph) a gun like I told him, we wouldn't be in this mess. But he got scared, and, duh, ran off and got hisself caught, the stupid little (bleep).

GERE: So Aaron did kill Rushman.

NORTON: What? Hell, no. Jesus Christ, where'd they find you? Ain't you been listening to me? Aaron don't have the guts to do nothin'. It was me, boy. It was me.

GERE: It was you.

NORTON: Yes, it was.

GERE: It was you.

(END AUDIO CLIP)

GROSS: That's Edward Norton and Richard Gere in a scene from "Primal Fear."

So this was your first movie role, a big part. How did you get it? How did you get it? How'd you get such a good part the first time out?

NORTON: I don't know. That was weird, listening to that for me, because I haven't -- I don't think I've watched that movie since the week it came out, which was about four years ago. And I was listening to those lines. I haven't even thought about them for a bunch of years. I was listening to it, like, I can't even remember that's what that scene was about. It was wild.

I just haven't revisited it in a long time.

GROSS: You have a foul mouth, sir. (laughs)

NORTON: Yes, well, yes, that guy, he's a tough character. But that was very interesting. The -- we improvised a lot in those scenes, so a lot of that was just stuff I kind of -- you know, we kind of riffed around the basic components of the scene, and Richard was really good at that. So it was fun to do.

GROSS: So how did you get the part?

NORTON: Well, it was a situation where they -- obviously by its nature, it's a part -- it's a role that has to do with first impressions and deceptions and kind of acting within acting. And I think that, wisely, Greg Hoblit was aware that the -- it was something that if the audience could actually be fooled in the same way that the lawyer is being fooled, it would be very effective, as opposed to, you know, if it was an actor that people were familiar with, and so they were aware of the artifice on some level from the beginning, that that could kind of diminish it.

And I -- I think he was very intent on trying to find someone who was unfamiliar to audiences. And so as a result, he -- they engaged in a -- you know, in an audition search. And so it was a very unusual circumstance, a very, very good part where they were really looking around.

And they went all over the place, and I was obviously acting in New York in a theater at the time, and the casting director for Paramount had seen me in some plays, and brought me in among many, many others to audition for Greg. And it kind of went on from there.

GROSS: Was this audition an interview or did you have to do lines from the part?

NORTON: No, no, no. It was -- it's always -- if they're doing it right -- I mean, I think one of the worst things that can happen in an audition is when you walk in the room and there's the director and producer, and they start talking to you, because it's just like -- I mean, try to imagine going to see, you know, Dustin Hoffman in "Rain Man," and before the movie starts, a little thing comes up on the screen, and Dustin Hoffman says, "Hi, I'm Dustin Hoffman... "

GROSS: (laughs)

NORTON: "... I'm about to play this role, and I hope you all enjoy the film." And then you watched him play that character. It's like -- it just punctures...

GROSS: Absolutely.

NORTON: ... it punctures the bubble. And I think -- I've always said, whenever I've gone to classes or, you know, to places where actors -- younger actors want to ask questions and things like that, one of the things I've always said, is, Don't let them do that, you know, when you go into an audition. Do not let them talk to you beforehand. Because it's like -- it's just like cutting the legs out from under everything you're about to try to do, which is to say, fool them in the same way that you're going to fool an audience.

Even when it's not such a deceptive character, even when it's not a character who is try -- who is pulling such a trick on people, even if it's just a, you know, me playing -- oh, I don't know, you know, like any of the characters I've played in films. You don't want to walk in and talk and be yourself and then launch into this character, because it's automatically going to sort of seem more like a put-on.

GROSS: What would make it even worse, I think, is that you had to do a Southern accent for this, so...

NORTON: Yes, accents...

GROSS: ... they hear your regular accent, and then they go, Oh...

NORTON: Especially, absolutely. I have a theory about accents, which is that if someone -- I mean, I think if you walked up to any -- even if you did a bad British accent, say, if you walked up to someone and you were doing it, and that was the first time they met you, no one would question it. Whereas, you know, I could walk up to a lot of people right now and do an absolutely flawless British accent, and by virtue of the fact that they know that I'm not British, they'd be saying, Oh, well, that kind of doesn't sound right to me.

I think people have a very relative -- their critique of things is relative to how intent -- how aware they are that you're doing a put-on, you know. And I think when actors have to do an accent or anything like that, they have to go into an audition, it's the worst thing in the world is to have to talk to the people beforehand and then launch into this, you know -- Because they're going to -- in their minds, they're going to go, Ahh, I don't think he's doing that that well, you know.

GROSS: Edward Norton is my guest, and he directed and stars in "Keeping the Faith," and also -- he plays a priest, Ben Stiller plays a rabbi, and Jenna Elfman plays the woman they both love. It's a romantic comedy.

Let's take a short break here, and then we'll talk some more.

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

GROSS: My guest is Edward Norton, and he directed and stars in the new movie "Keeping the Faith."

Let's get to another movie that you made, "American History X," in which you played a skinhead who ends up being arrested and then undergoing a personality transformation in prison.

So here's a scene from the first part of the movie, in which you're a skinhead trying to incite your group to action by convincing them that they have to take back their community from the foreigners who are moving in.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, "AMERICAN HISTORY X")

NORTON: On the Statue of Liberty it says, "Give me your tired, your hungry, your poor." Well, it's Americans who are tired and hungry and poor. And I say until you take care of that, close the (bleep)ing book, because we're losing. We're losing our right to pursue our destiny, we're losing our freedom, so that a bunch of (bleep)ing foreigners can come in here and exploit our country.

And this isn't something that's going on far away, this isn't something that's happening places we can't do anything about it. It's happening right here, right in our neighborhood, right in that building behind you. Archie Miller ran that grocery store since we were kids here. Dave worked there, Mike worked there. He went under, and now some (bleep)ing Korean owns it who fired these guys, and he's making a killing, because he hired 40 (bleep)ing border jumpers.

I see this (bleep) going on now. I don't see anybody doing anything about it. And it (bleep)ing pisses me off.

So look around you. This isn't our (bleep)ing neighborhood, it's a battlefield. We're on a battlefield tonight. Make a decision. Are we going to stand on the sidelines, quietly standing there while our country gets raped?

ACTORS: (inaudible)

NORTON: Are we going to ante up and do something about it? (bleep)

ACTORS: (inaudible)

(END AUDIO CLIP)

GROSS: Edward Norton in a scene from "American History X."

Did you have to do anything to convince the director that you could get really pumped up, physically pumped up, for the role?

NORTON: No, it wasn't specifically about the physicality, it was more when I met the director, Tony Kaye, I was just coming off of doing "Larry Flynt," and it was -- you know, I had sort of that, you know, lawyer's haircut. My hair was dyed a little darker, and I was thin, and it just -- I think he had a lot of respect. He said, you know, very, very complimentary things to me about all the films he'd seen me in, but I think he completely rightly -- his perception of the character was that he needed to be kind of like the ueber-skinhead, that he needed to be -- Tony used to say, He needs to be like the Marlon Brando of skinheads, that he needed to be, you know, very charismatic, very forceful.

And he was never saying specifically, you know, You're too small, but I think he was very intent on having this guy be someone who's forceful in all ways. And I agreed with him. And so we -- I said, Look, look, look, take -- give me about a month and a half, and I went away and just kind of did about halfway what I ultimately did for the film, just kind of beefed up a little bit, shaved my head, grew a beard, all that. And we shot some test film together where we just kind of riffed on speeches exactly like that.

And he filmed it in black and white in kind of the style he was going to film it in, and we looked at it together. You know, because I wanted to see too if I felt it was something I could hit to my satisfaction, and we were both very pleased with where we -- the zone we thought we were getting into. And that was when we decided to do it together.

GROSS: Well, when you were in high school, did you ever think that you had the personality that would allow you turn on the kind of charisma you had to have in "American History X"?

NORTON: I don't know if in high school specifically. I think when I was in college, I did -- I mean, I did a lot of theater, and it was -- I had been doing theater since I was a kid, (inaudible) 5 or 6 years old. And I don't recall specifically if, in my younger life, I did anything that was kind of -- had that kind of level of intensity. But I -- in college, I got the opportunity to work on a couple things that were in that kind of zone. I mean, obviously not a skinhead, but I did feel at a certain point a -- that -- I had kind of a facility for tapping into those kind of reserves for those kinds of parts.

I -- when I was talking about "Primal Fear," that scene you played, when I auditioned for "Primal Fear" initially, the -- when it got down to sort of a screen testing level, I was definitely aware that they were -- the thing they were more concerned about was whether I could play the young innocent guy that -- the kind of guileless, stuttering -- you know, could I -- could he be vulnerable enough? Because they were thoroughly, you know, sold on the kind of scene you played, that tough guy thing.

And I think I've always been able to hit that, the, you know, kind of territory, I don't really know why. But I think everybody's got certain things, you know, they are able to connect with...

GROSS: Well, let me ask you, you know, you don't have the kind of body, I don't think, that goes along with that, you know, tough guy, charismatic, I can do anything, you know, in your face kind of role. But did you have, like, a little cartoon in your head in which you were that person? (laughs) You know, just like someplace in your inner life?

NORTON: Yes, yes, sure. I mean, I think you have to. I think you have to find that place. I had it different times. I mean, at one time I'd been playing sports really seriously in college, and I was much bigger. I was more of that size. So I had had the experience of -- I knew I could get to there physically, and I knew that I could get there, I think, with -- it wasn't so much that as it was just, you know, connecting -- It was -- in some ways you have to just kind of bite the bullet and go all the way there in terms of the brutality of this guy's anger.

And I think to get in that place, you have to feel like you're in a fairly safe environment in terms of your working collaborators. And the good thing about "American History X" was that it was a, you know, wonderfully multiethnic, multiracial, multidenominational cast and crew, all of whom were very -- it was done for a very low budget, and everybody was doing it very much out of the feeling that it was about something valid and important that was making an important human statement, I think.

And so there was -- I had a lot of support, you know, within the working environment, and I -- and therefore I felt very free to, you know, to go all the way with it, to be at that dinner table with Elliott Gould and just letting him have it on all kinds of horrible, you know, horribly abusive levels. And Elliott was there supporting me and sort of saying, I thought that was really great, and more of that, do more of that, you know. And that's kind of the key, I think, to being able to take it -- something -- a character like that all the way out to its natural extreme.

GROSS: Edward Norton. He directed and stars in the new film "Keeping the Faith." He'll be back in the second half of the show.

I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

Here's Tom Waits from the sound track of "Keeping the Faith."

(AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, "KEEPING THE FAITH" SOUND TRACK, TOM WAITS)

(BREAK)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR.

I'm Terry Gross, back with Edward Norton. He directed and stars in the new romantic comedy, "Keeping the Faith." His other films include "Primal Fear," "Everyone Says I Love You," "The People Versus Larry Flynt," "American History X," and "Fight Club," which will be out on video later this month.

"Fight Club" is a movie about people who, who, who find meaning in life by joining this very secret club in which they fight each other, fight each other quite, quite hard. I'm going to play a clip from early in the movie, where all we really know about your character is that he's a young guy who's just really disenchanted with the life he's found himself leading, worrying about shopping for the right bedspread and the right coffee. And he's a numbers cruncher for a car maker, and he's become an insomniac.

So he tries to find peace of mind by attending support groups for problems he doesn't even have. His job requires him to do a lot of traveling, you know, by plane, and this is him thinking about all the travel and all the trivialities and mind-numbing stuff that it leads to.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP, "FIGHT CLUB")

NORTON: You wake up (inaudible), (inaudible), (inaudible). You wake up at O'Hare, Dallas-Fort Worth, BWI, Pacific, Mountain, Central, lose an hour, gain and hour.

ACTRESS: Check-in for that flight doesn't begin for another two hours, sir.

NORTON: This is your life, and it's ending one minute at a time. You wake up with (inaudible) national. If you wake up at a different time, in a different place, could you wake up as a different person?

Everywhere I travel, (inaudible) new life, single serving sugar, single serving cream, single pat of butter. The microwave cordon bleu hobby kit. Shampoo-conditioner combos, sample packaged mouthwash, tiny bars of soap.

The people I meet on each flight, they're single-serving friends. Between takeoff and landing, we have our time together. That's all we get.

(END AUDIO CLIP)

GROSS: That's kind of like the urban neurotic alienated professional version of rap. (laughs)

NORTON: (laughs)

GROSS: Did you do that voice-over with the music or without it?

NORTON: No, no, without it, without it. We spent a lot of time in booths like this one working -- we tried every kind of mike, every -- close to the mike, far from the mike. We experimented just into infinity with finding exactly the right tone to create the feeling of that voice that's in your head, so that it would have a quality distinct from sort of what we're used to hearing in voice-overs, you know, of really almost being inside the brain, that voice you're talking to yourself with, you know.

But -- and the narration obviously -- it was such a critical component of the novel that we felt it needed to be a part of the film as well.

GROSS: Is narration very hard because it's not like you're talking to somebody, and yet you have to make it really believable as that inner voice?

NORTON: It is, it is. It's -- and it has to be a characterization. It -- I mean, especially in the case of this film, where the underlying reality -- truth -- the underling truth of the film is revealed to be something very different from what the narrator himself is presenting it as.

I mean, it's a bizarre comparison, in a way, but, you know, I've always thought what's great about a book like "The Catcher in the Rye" is that it's told in a first-person narrative by a narrator who's not a very reliable, you know, source of perspective on himself. And you learn things about Holden Caulfield that he's not really telling you about in the dialogue, in the scenes where what he's saying to people kind of goes against what he's saying to you in his inner monologue.

And this reminded me of that, because my character in "Fight Club" is a totally unreliable source of information about himself. He's telling you a version of his story that, as the story goes along, you realize is a completely deluded understanding of his own problems. And so you have to make -- that has to be -- the voice-over can't just be a narration, it has to be a characterization.

GROSS: Which leads me say, without giving away too much of the story, that you've played a lot of, like, double personalities and double roles in your career, where your character has -- undergoes some kind of transformation as both good guy and bad guy.

NORTON: Yes.

GROSS: Why do you think you've had so many roles like that? (laughs)

NORTON: Well, I think that -- I mean, I think that any character should undergo a transformation. I mean, that, to me, is what drama is about. It's like, I had a good acting teacher one time who said, you know, You should always be able to look at a scene, and certainly a whole piece, and say, you should be able to look at a drama and identify the -- you know, what happens that changes things in it. I mean, a story should be at its fundament, you know, something happens as a result of which something changes.

And if -- to me, if a character doesn't transform on some level in a story, it's not worth playing, because it's -- I think that's why people are going to movies, to plays, reading novels, because the -- you want to read about people evolving in some way. That's what you connect with. And I think that in "Fight Club," you know, it's very different from "Primal Fear," in the sense that it's -- I mean, "Primal Fear" is about somebody par -- acting, basically. "Fight Club" is about a person actually going insane...

GROSS: Right.

NORTON: ... and not knowing that he's going insane. And obviously I don't play both halves of his personality, I play one half, and I play the half that is learning -- that comes to -- has a -- a guy who has to come to grips with the fact that he's crazy and has to realize how crazy he's gone.

So even though on a loose level there -- it's connected with "Primal Fear," it really was a very different sort of a thing. But it is -- but what I liked about it is, it's a character who -- he changes, he -- his sense of his own desperation in the beginning leads him to experiment with a kind of a solution that he ultimately realizes is very, very negative and very unhealthy, and from which he pulls back. And finally, by the end, you know, defines himself. He finally, I think, on a certain level, right at the end, figures out who he is on his own.

GROSS: My guest is Edward Norton. We'll talk more after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

GROSS: Edward Norton is my guest.

Let's get to another one of your movies, "Everyone Says I Love You," which was Woody Allen's musical in which he had actors who really aren't singers singing songs for the film. You had two songs, "Just You, Just Me," and "My Baby Just Cares for Me." Let's hear a little bit of "My Baby Just Cares for Me."

NORTON: Oh, God.

GROSS: (laughs)

(AUDIO CLIP, EXCERPT, "MY BABY JUST CARES FOR ME" FROM "EVERYONE SAYS I LOVE YOU," EDWARD NORTON)

GROSS: Edward Norton, what were your thoughts when you found that you had to sing in order to be in Woody Allen's movie?

NORTON: They -- I felt much the same way I feel right now having played that back in my ear. I -- it was -- it's -- I feel like putting a paper bag over my head.

GROSS: (laughs)

NORTON: You're officially turned this into a torture booth now that you've played my -- played me singing back to myself.

GROSS: (laughs) Did you know right at the start that singing was essential for (inaudible)?

NORTON: No, nobody knew. I remember when I -- I remember when I met Woody for the second time, and it seemed to be going well in terms of, you know, him wanting me to do the part. Right toward the end, you know, he came over and he went, you know -- I read a scene, and he went, "That was perfect, that was great. Now, by the way, do you sing at all?" you know. And I kind of went, "What? You know, sure, you know, in -- not in a great way, but as a character, a singer (ph)?" And he went, "Well, you know, I'm not looking for Pavarotti, I'm just -- just something I'm playing with." You know, and I was going, Hmm, I wonder what that's about.

So I got the part, and I was all excited, and about a month -- you know, a couple months went by, and about a month before we started shooting, I got this call from Dick Hyman, who's Woody's longtime music supervisor and arranger and kind of genius of orchestration and arrangement. And, you know, and I -- he said, "I'm going to have you get together with a, you know, a voice person in Los Angeles, because we need to get your range." And I went, "What -- you know, what is this for?" And he said, he said, "Well, we're making a musical."

And I -- you know, I kind of, like, started hyperventilating. And apparently everyone else had pretty much the same experience, because he didn't really -- he didn't want to give anybody any time to panic and go out and, you know, work on it. He wanted everybody to sound -- the whole idea was, people coming off the -- you know, the characters, like normal people just bursting into song with all their, you know, cracking voices and everything. He didn't -- he did not want a polished thing, so...

GROSS: Nevertheless, did he want you all to take some voice lessons?

NORTON: No, not at all...

GROSS: No coaching, nothing?

NORTON: ... he insisted that we not do it. And in fact, when I went and laid down -- we prerecorded the songs so that we could sing back to our -- you know, lip-synch to our -- or sing along with our own playback when we filmed it. And I prerecorded the songs, and, you know, of course I had worked on them. There was no way I was going to go in cold. And I did it, and about a week later, I got a call, you know, and they said, "Woody wants to talk to you about what you recorded." And I panicked, you know, I just went, Oh, no, I'm getting fired, because Woody lets a lot of people go. It's kind of -- he -- Woody's famous for, you know, firing people.

And I thought, This is it, I'm out. And I went back in to see him, and he said, he said, you know, "We need to do it again, because you sound too good, you sound like Perry Como," you know.

GROSS: (laughs)

NORTON: "And you need to scale it back a little bit." So he actually made me come in and do it worse. I had a couple tracks, I had a couple tracks that I was really happy with, and, and, and he made me come in and kind of sing it more like a guy on the street, you know.

GROSS: So what impact did this movie have on your own self-consciousness about singing?

NORTON: I -- I -- I -- I've -- I try to shut it out, and occasionally someone will do what you just did and throw on the sound track, and it'll all come raging back to me like a -- like a...

GROSS: Like a bad dream. (laughs)

NORTON: No, the experi -- no, I'm kidding, I'm kidding. It's just hard to hear it, you know, disconnected. I love watching it in the film, because the film -- I think the film is, you know, so light and funny, and the (inaudible) -- actually that song, "My Baby Just Cares for Me," is the one in the Harry Winston's jewelry store where the whole musical number erupts in the jewelry store. And I think it's a hilarious sequence.

But out of context, it's a little bit like looking at your high school yearbook pictures.

GROSS: What kind of music do you most enjoy listening to?

NORTON: I listen to everything. I mean, I go through phases and waves and stuff. But lately, I -- directing this film, obviously I've been paying a lot of attention to the music, and one of the things I wanted to do with the film was -- it obviously is a romantic film, it's a romantic comedy, and it -- it's -- it was very much, for me, a chance to sort of do a Valentine to New York, which I've lived in New York for 10 years and always think it's the most romantic city.

But I wanted to try to put -- Stewart and I talked a lot about trying to put our spin on it. So we focused -- I focused a lot on what were my big New York walking-around records, and who were the artists that for me kind of were the sound track in my head to New York. And, you know, for me -- for Woody Allen, it might be Gershwin, and Nora Ephron it might be, you know, a certain era of songs. But for me, it's, like, Tom Waits and people like Eliott Smith (ph) and a friend of mine who I used to listen to down in the Village a lot, little cafes, and so I went through a lot of their music and put it in.

And I found a lot of contemporary jazz artists that I like, people like Cyrus Chestnut (ph) and a lot of the Cuban jazz artists from the -- that Buena Vista Social Club we worked in there. So that was -- that's kind of the -- musically, that's what I've been focused on lately is finding a good sound track to the film. And then in addition, fortunately, we were very lucky to get Elmer Bernstein to write, you know, some really beautiful scoring for it. So...

GROSS: Must have been great to work with Elmer Bernstein. I mean, he's written...

NORTON: It was amazing, it was...

GROSS: ... such great stuff.

NORTON: ... amazing. He is a legend more than, I think, than a lot of people know. I think he's arguably -- I think he's arguably the greatest living film composer in terms of his overall career. He's done a minimum of three film scores a year since 1955, and it includes everything from "The Ten Commandments" and "To Kill a Mockingbird" to, you know, "Hud," "Great Escape," "Magnificent Seven," all the way up through, like, "Airplane" and "Animal House" and...

GROSS: "The Grifters."

NORTON: ... "The Grifters," and Scorsese's late film -- later films, you know, "Age of Innocence" and "Bringing Out the Dead." I mean, it goes -- I can't even -- he did the first all-jazz score for Frank Sinatra, "Man With the Golden Arm." He did "Sweet Smell of Success." I mean, it just -- you look at his list of credits, and you can hardly believe how much great music this guy has written. And he's almost 80 years old, and he's like a 16-year-old. His energy is just incredible. He was a very, very inspiring person for me to work with.

And he wrote just beautiful, beautiful music.

GROSS: Can you share one of the insights that he had to how the music should interact with the film? I mean, like something that he said -- said that made -- made you realize something you'd never quite thought of in that way before.

NORTON: Well, he did many, many things. I mean, he -- you know, I had been very, very specific in my cuing, you know, with the temporary -- with the temp music, which you always do before your composer comes on, and I thought I'd really nailed down everywhere I wanted music. And he came in and showed me a few places where -- you know, he just enhanced places I had thought didn't need music.

There's a scene where Ben Stiller and I are sitting on a basketball court talking, and -- before Jenna shows up, and he just added this funny little bunch of horns sort of going, (singing) Wah-wah-wah, wah-wah-wah-ah. And it just totally -- we get a big laugh at the end of that scene now that we had never gotten before, just because it kind of has a funny, you know, Laurel and Hardy kind of a feel to it, or, I don't know, it's -- it just enhances the sense of these two guys who have known each other for a long time, and the banter they have going between them.

But Elmer also -- you know, there was one place where I had thought about cutting this one shot of Ben walking across the street alone at night, sad, sort of -- because he can't -- you know, he hasn't met somebody that he likes, and -- a woman that he likes. And Elmer -- I'd thought -- I had said, you know -- my editor and I were talking about trimming it, and Elmer said, you know, "Let me have this moment and write the right kind of music for you, and -- because it's the... " He said it was the kind of moment you need to feel empathy for this guy. And he was totally right, you know, so his input was not just purely musical, it was almost, you know, emo -- he -- he -- he had a la...

GROSS: Psychological.

NORTON: ... he focuses -- yes, he focuses on the emotions of the characters, and he -- and what a person might -- what a composer does that I think a lot of people aren't aware of is that they help create an emotional connective tissue, because they -- instead of just piecemeal music, they create themes for you, you know, and subtly those themes -- like, there's a theme for Jenna's character, a theme for my character, a theme for me and Ben together.

And as those themes recur, you realize that it gives emotional resonance. And it's amazing to work with a guy like him. There are very few people left who are as -- who are classical -- classically trained composers like he is who are still focused on movies this way.

One other little amazing thing about Elmer is we were talking one time about this film, Tim Robbins did "The Cradle Will Rock," which is about that period in the '30s when Orson Welles was doing the theater in New York, and this kind of dramatic incident that took place. And I was talking to Elmer about whether he liked the music in the movie. And he said, he said, "Yes, it was very accurate to the evening." And I said, "What do you mean?" And he said, "Well, I was there."

GROSS: (laughs)

NORTON: And he was at that -- he was at that evening when they marched up to the other theater, and the actors performed from the seats and everything. And it was just -- you know, he went through the whole blacklist period, and it -- he's just an incredible amount of history.

GROSS: Much as you love Elmer Bernstein's work, was there a point where you had to off -- off -- offer some critical advice and say, I don't like this, can you do it over?

NORTON: Absolutely. Absolutely. And that was, to be totally honest, it was a -- one of the things I admired most about Elmer was, you know, I mean, he is a living legend, and I'm this, you know, first-time director. And he -- the guy was utterly without ego. I mean, it wasn't that he would -- you know, he would tear his hair sometimes and go, "Impossible!" you know, "There's no time!" And yet he would -- and then he would hunker down and do it.

And he -- that level of kind of commitment to the process was just amazing, and I think it helped on some levels that I have had some musical background. And so we were able to talk in musical terms together, in, you know, terms of major and minor, and just some musical fundamentals that made it easier for us to communicate. And then -- and for me to editorialize to him.

But he -- but yes, and you have to take a deep breath in those moments, because that's what directing is about, it's about kind of trying to be open to other people's ideas and then -- but still remain true to your own vision of how it's supposed to work. So the first time, you just have to take a deep breath and turn to someone like Elmer Bernstein, and say, you know, I think that this is too light a treatment of this moment. I think it needs a little bit -- I need this moment to feel a little more poignant.

And hopefully you -- if you're lucky, you've surrounded yourself with people who are also committed to that collaborative process, and don't tell you to, you know, just buzz off, because you're -- who are you, you punk kid? Tell me how to do my music! You know, fortunately he wasn't like that, he was great.

GROSS: Edward Norton. He directed and stars in the new romantic comedy, "Keeping the Faith."

Coming up, we remember writer and illustrator Edward Gorey.

This is FRESH AIR.

(BREAK)

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest: Edward Norton

High: Actor Edward Norton's first major role was in the 1996 film "Primal Fear" as a quiet, stuttering altar boy accused of a brutal murder. He was nominated for an Academy Award for his portrayal. Norton went on to roles in Woody Allen's "Everyone Says I Love You," "The People vs. Larry Flint" and "Fight Club." He was nominated for an Academy Award again for his role in "American History X." He directed and stars in the new film "Keeping the Faith."

Spec: Entertainment; Art; Movie Industry

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 2000 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 2000 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Edward Norton Discusses `Keeping the Faith'

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: APRIL 17, 2000

Time: 12:00

Tran: 041702NP.217

Type: FEATURE

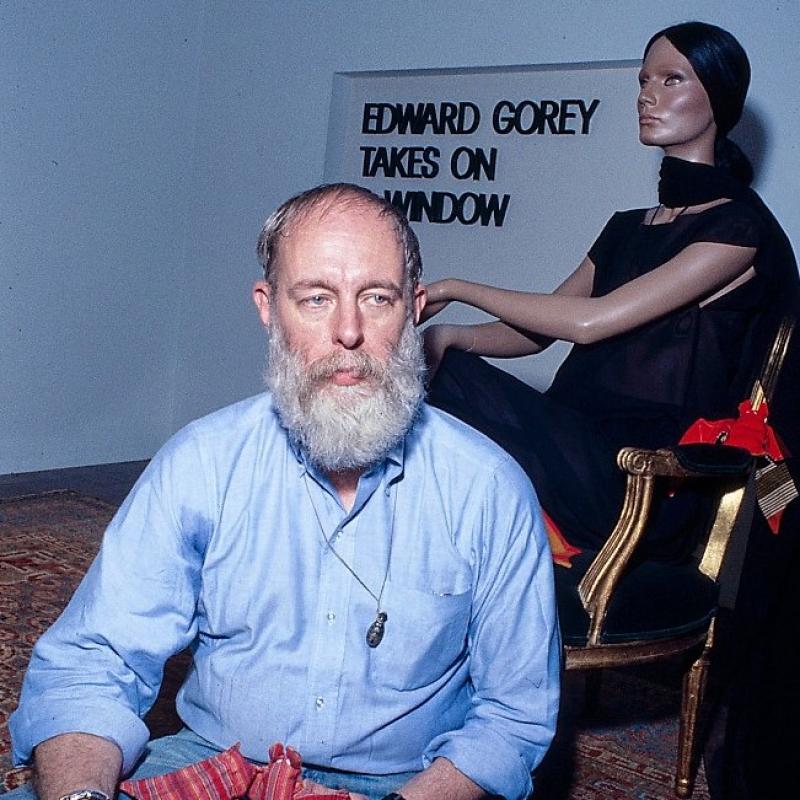

Head: Illustrator Edward Gorey Dies at 75

Sect: News; Domestic

Time: 12:52

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

TERRY GROSS, HOST: The eccentric and beloved writer and illustrator Edward Gorey died on Saturday at the age of 75 after a heart attack.

In today's "New York Times" obituary, Mel Gussow described him as "a grand master of the comic macabre who delighted readers with his spidery drawings and stories of hapless children, swooning maidens, throbble (ph)-footed specters, threatening topiary, and weird, mysterious events on eerie Victorian landscapes."

Gorey's Alphabet Books were sinister comic versions of children's books, with rhymes like, "W is for Winnie, embedded in ice; X is for Xerxes, devoured by mice." They were illustrated with his detailed cross-hatched drawings.

In 1992, I did a brief phone interview with Edward Gorey.

(BEGIN AUDIO CLIP)

GROSS: Now, you never studied art, right?

EDWARD GOREY: Very little.

GROSS: So did you teach yourself the kind of detailed pen and ink style that you developed?

GOREY: Yes, I suppose I really did.

GROSS: Are you very patient? Because I figured you'd have to be in order to work with that kind of detail.

GOREY: Yes, reasonably so. I mean, I remember -- well, it goes in fits and starts. I mean, I sometimes think now that I've been doing this for so long, I think, Oh, good grief, I've got to sit down and, you know, draw, draw, draw. But there were periods -- I mean, I know when I was working on the drawings for "The Hapless Child," I'd done about, oh, five or six of them, I think, and I was in the middle of drawing the wallpaper on the wall, and I thought, I am bored to death drawing wallpaper on the wall.

And I put the book aside for about five years.

GROSS: You see a lot of movies, yes?

GOREY: I used to. I now see a lot of television.

GROSS: How come you don't go to the movies much any more?

GOREY: I don't know whether it's me. I don't think it really is. I think -- I don't think movies are where it's at any more. I mean, I go out -- maybe I've been to two movies this year, which, you know, when I look back, there was a -- in my heyday of movie-going, I saw -- I used to keep list -- keep a diary with the movies I saw, you know, without any criticism or anything. I'd just jot down which movies I -- And for quite a few years in New York, I used see over 1,000 movies a year.

GROSS: That's an awful lot. That would be, like, three a day (inaudible).

GOREY: That's right, it was more than three a day.

GROSS: So that's...

GOREY: I mean, (inaudible), it wasn't that I was at the movies every day, but I would go on these -- I had friends who had collections of movies and ran film societies and things. We would have 24-hour orgies of movies and things like that, so managed to rack up rather an alarming number of them.

But lately, I don't know, I go off and I (inaudible) -- actually, I think television is much more interesting now, for the most part.

GROSS: What do you watch on TV?

GOREY: Oh, everything from -- mostly trash, frankly. I mean, Masterpiece Theater I usually begin to sort of glaze over, and I switch over to the nearest trashy movie.

GROSS: What's your typical day like?

GOREY: Oh, my typical day is fighting off several of the cats in the morning, and then struggling up and thinking of all the things I should be doing and probably won't get around to. And -- well, I try and work every day to some extent. I mean, I do work every day to some extent, but sometimes there are days when I feel like I've been sitting around to, you know, absolutely no avail whatever.

GROSS: You live with seven cats. How did you end up with so many of them?

GOREY: Oh, well, oh, one thing led to another. I used to -- when I was living in -- or when I was going back and forth between here and New York and everything, I used to try and keep it down to three. And for a long time I did keep it down to three. And then somehow it went up to six. I can't really remember quite why. And I have been as high as nine. Briefly I had nine a couple of years ago.

GROSS: But you're not one of those cat cartoonists.

GOREY: No. I draw cats occasionally, but not -- no, I don't -- actually most of the cats I draw are anthropomorphic rather than cat cats. I occasionally put a cat in a drawing, but not terribly often, and I don't -- I feel they're the last mystery, so to speak. I...

GROSS: Mysterious in what way?

GOREY: Well, they're just, you know -- I think one of the things I like about cats, of course, is they don't talk. I mean, they talk, but you can't understand what they're saying, so it doesn't really much matter. And they're -- you know, they're -- they have the -- they have -- well, of course, the sleep 90 percent of the time anyway. So, you know, most of the time you're looking at a lot of sleeping cats. But then occasionally they wake up and go crazy, and you wonder, Why are they going crazy? and so forth.

They are rather affectionate, and they -- you know, it's company.

GROSS: A lot of the people who you draw seem strange, odd. Is that how a lot of people strike you in general?

GOREY: Oh, well, I sometimes feel, with all the practice God has had making people, He hasn't done a very good job of most of us. But no, I -- it's -- it's sort of -- I mean, the longer I go on, the more I feel it's very hard to, you know -- the relation between, you know, your work and life and whatnot, I mean, I obviously, you know, I obviously don't do anything very terribly realistic. But on the other hand, I (inaudible) -- you know, I'm obviously getting my inspiration, whatever you want to call it, from, you know, from reality, but I -- the relation is sort of very strange.

(END AUDIO CLIP)

GROSS: Edward Gorey, recorded in 1992. He died Saturday at the age of 75.

FRESH AIR's executive producer is Danny Miller. Our engineer is Audrey Bentham. Dorothy Ferebee is our administrative assistant. Roberta Shorrock directs the show.

I'm Terry Gross.

TO PURCHASE AN AUDIOTAPE OF THIS PIECE, PLEASE CALL 877-21FRESH

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest:

High: Macabre cartoonist and illustrator Edward Gorey died on Saturday at the age of 75 of a heart attack. His illustrations are the opening credits of the PBS show "Mystery." He wrote over 100 books, including "The Gashlycrumb Tinies," an alphabet book that began "A is for Amy who fell down the stairs." One of his other books, "The Doubtful Guest," was a classic, about a creature who shows up uninvited at a dreary mansion and becomes a member of the family. Toward the end of his life, Gorey lived in a 200-year-old house in Cape Cod, with his five or six cats.

Spec: Art; Entertainment; Death

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 2000 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 2000 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: Illustrator Edward Gorey Dies at 75

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.