Contributor

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on September 7, 2018

Transcript

DAVE DAVIES, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies in for Terry Gross. Most of us have had the experience, driving on an interstate, of looking up at the driver of a tractor-trailer next to us and wondering what's his life like. Living on the road, hauling a 75,000-pound rig with a trailer more than 50 feet long, our guest Finn Murphy has written a memoir about his experiences logging over a million miles on the nation's highways. His cargo is the furniture, dishes, clothing, pianos, heirlooms and artwork of corporate executives and their families moving across the country to new homes for their new jobs.

His memoir, now out in paperback, is filled with insights about life on the road and the subculture of truckers, as well as the attachments people have to their possessions when they're transitioning to a new home - trying to decide what to keep and what to ask Murphy to throw in the dumpster. He dropped out of college to become a truck driver. He's been doing this work on and off since the late '70s. Terry spoke to Finn Murphy in February about his book "The Long Haul."

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

TERRY GROSS, BYLINE: Finn Murphy, welcome to FRESH AIR. I want to start with a reading from the book, a short paragraph from the introduction.

FINN MURPHY: (Reading) To the casual observer, all trucks probably look similar. And I suppose people figure all truckers do pretty much the same job. Neither is true. There's a strict hierarchy of drivers depending on what they haul, how they're paid. The most common are the freight haulers. They're the guys who pull box trailers with any kind of commodity inside. We movers are called bedbuggers, and our trucks are called roach coaches. Other specialties are car haulers - we call them parking lot attendants; flatbedders, skateboarders; animal transporters, chicken chokers; refrigerated food haulers, reefers; chemical haulers, thermos bottle holders; and hazmat haulers, suicide jockeys.

Bedbuggers are shunned by other truckers. We will generally not be included in conversations around the truckstop coffee counter or in the drivers' lounge. In fact, I pointedly avoid coffee counters when there is one mostly because I don't have time to waste but also because I don't buy into the trucker myth that most drivers espouse.

I don't wear a cowboy hat, Tony Lama snakeskin boots or a belt buckle doing free advertising for Peterbilt or Harley-Davidson. My driving uniform is a 3-button company polo shirt, lightweight black cotton pants, black sneakers, black socks and a cloth belt. My moving uniform is a black cotton jumpsuit.

GROSS: Well, thanks for reading that. And apparently you don't wear jeans or belts 'cause they can scratch the furniture.

MURPHY: Yes, that's correct.

GROSS: (Laughter) So why are long-haul furniture movers at the bottom of the trucker hierarchy?

MURPHY: Because we have to load and unload our trucks, first. Second, we have to deal with customers. So as a mover who works for a van line, I'm managing this move and this transition for this family. And that takes a certain amount of diplomacy and tact and social lubrication skills that a lot of drivers don't want to do. And then the third one is we get paid a lot of money to do this. So we're at the top of the earnings pyramid, which puts us sort of at the bottom of the coffee-counter trucker pyramid.

GROSS: So describe your truck.

MURPHY: My truck - I have a brand-new Freightliner Cascadia with a 435 Detroit Diesel engine. It's a Class 8 truck, which means the big tractor-trailers. I picked it up in Indianapolis in November. It had 42 miles on it.

GROSS: Whoa.

MURPHY: Yep.

GROSS: Right out of the showroom (laughter).

MURPHY: Brand-spanking new. I drove it right out of - (laughter) yep, I drove it right out of the lot. It's got a walk-in sleeper with a double bed in the back. It's got a bunk bed up above, a microwave oven, refrigerator, navigation system, a custom air ride seat that ergonomically fits to my body, cruise control. It's just a wonderful machine.

GROSS: And you own...

MURPHY: It cost me...

GROSS: You own it.

MURPHY: No, (laughter) yeah, I was just getting to that. I don't own it. I lease it, and it's $4,700 a month - is my truck payment. So it's like a big mortgage.

GROSS: Yeah, bigger than some mortgages (laughter). So how does this truck compare to the truck you started driving back in - around 1980?

MURPHY: Oh, so that was an International TranStar back then, what we call a cab-over. So there's no hood to it. So you're - the windshield is sitting right over the road, and you're sitting actually right over the front left tire. So it was very - and then had a cramped little sleeper that I had to crawl into in the back. So it's much, much different in terms of comfort. So the new Freightliner I've got now is what we call a conventional, so it's got a long hood. So my seat sort of sits in the middle of the truck. I've got an air ride suspension. And it's quiet.

GROSS: Wow. If there's no hood in front, there's nothing to protect you from head-on crash.

MURPHY: No, there isn't. And so let's avoid that.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Yeah, good idea. So that leads to, what are some of the roads or road conditions that you fear most?

MURPHY: Hills I fear most. Snow and ice I fear. I fear rain and big cities. In fact, I love this question because I'm not sure that people think when they see a truck driver - they sort of look up, and they see somebody there, probably has big arms and way up high - that fear is a component of what we do every day. It's not something that drivers talk about, and I don't think it's something that four-wheelers - people that drive cars, we call them four-wheelers. We've got - in fact, we've got a whole nomenclature for (laughter) people that don't drive trucks. If you drive an ambulance, it's called a bone box. A school bus is called a cheese wagon. Motorcycle riders are called organ donors.

GROSS: (Laughter) Oh, gee.

(LAUGHTER)

MURPHY: Yeah. And we call motorcycle - they're called murdercycles. Some - I mean, I can't even see motorcycles most of the time.

GROSS: So have you ever been - I hope not - in an accident?

MURPHY: Nothing serious. I've been in a few fender benders here and there, some - trying to make a tight urban turn. I got stuck in Boston once where the truck - in Cambridge, I was trying to make one of those turns, and the truck came right up against one of the lamppost things. And the cops came. And in Cambridge, they actually have a department in the police department. And this truck came out. They cut down the lamppost, got my truck out. Then they welded the lamppost back up. It took about 15 minutes.

GROSS: Wow, (laughter) OK. So when people hire you to move all their possessions - and mostly you have very high-end clients - they're leaving all their possessions in the world to a stranger. And no matter how, you know, nice and diplomatic and caring you are when you meet them, you're still a stranger. What do people say to you to try to convince you to be nice to their stuff and take (laughter) good care of it because I'm sure there's really, like, nice ways of doing that and really, like, threatening ways of doing that.

MURPHY: Yeah, so moving hits people right there in the - in that security spot. So on - when I show up on moving day, in fact, really what happens is - what happens in the first five minutes of a move is almost going to dictate the tenor of how the day is going to go. So people are already - you know, it's very disruptive to a family. It's disruptive to children. It's disruptive to the parents. Usually there's a change in their jobs and so forth. So even before we get there, this is fraught with emotion.

And then, you know, you've got the reputation of the moving industry, which is - you know, I'm very aware of the dismal view that the general public has about movers. And I try to assuage that as much as possible early on and to let them know that we're professionals, that we care about their things. But that said, some of the crews that I work with - I mean, we're talking about, you know, very big people (laughter). There's a lot of tattoos. It's all immigrant laborers - wonderful, wonderful people. And I have crews all over the country I've been working with for decades. But it can be a kind of unnerving initial physical presence at the beginning.

GROSS: So you're entrusted with the possessions, and sometimes something goes wrong. And I think, like, the biggest example of that in your book is when you were moving a family, and the woman's baby grand piano was, like, the most prized possession of - was, like, a family heirloom in addition to being a piano. And it didn't really fit easily into the new home. And it was kind of a catastrophe. Would you describe what happened?

MURPHY: (Laughter) It was a catastrophe. The first - the three words that all movers live by is not my fault (laughter). And so we had to bring this up an outside staircase. It was a baby grand piano, weighed about 700 pounds. And we were bringing it up the incline just with brute force, which is one of the really attractive things about the work that I do and that we do as moving crews. And so we were just manhandling this thing up. And as we got to the top of the stairs which was being held by those two sort of metal joist hangers, the joist hangers gave away. The piano fell about 14 feet down onto the ground. All of my movers scattered in all directions. And when the piano hit, it made - you know - remember that chord at the end of the "Sgt. Pepper" album...

GROSS: Yes.

MURPHY: ...When it goes boing? So that's the noise that the piano made. That was its death flurry. And we were all just shocked and standing around. And the customer was there with a toddler in her hand. And then the thunderstorm came, and it just started to rain on everything.

GROSS: That's so horrible.

MURPHY: And myself and my crew - we just looked over at the shipper. We call the customer the shipper. And one of my men, this big giant of a man, went over and put his arm around the customer, the shipper. And then the two of us went over, and we all just sort of put our arms around each other, watched the piano get soaking wet in the rain.

GROSS: So you write that that truckers like you aren't sentimental about objects. I'll kind of leave a baby grand out of that because that's an instrument. That's different than (laughter) an object in my opinion. But so you write you're not sentimental about objects. You don't own much. I could easily see it being the other way around. Watching how meaningful possessions are to people, I could see you becoming more attached, not less attached to things in your life. So why are you less attached?

MURPHY: Because we see objects or stuff in a continuum of the way people live. For example, in your 20s and 30s, most Americans are accumulating things. And then in the 40s and 50s, that sort of levels off. And then in the 60s and 70s, then they're dis-accumulating things or eradicating things. So we get to watch the whole continuum. So we see, for example, that the kids' kindergarten drawings that are on the refrigerator or the high school yearbook or Aunt Tilley's (ph) antique vanity - we see that those things are going to be put into storage at some point. And then when somebody is tired of paying the storage fees, then we're paid to take it and get rid of it.

So movers are kind of Buddhist in a way. We sort of understand the transitory nature of manmade things because we're there at the point when it gets thrown away. So even if you can't bring yourself to get rid of your stuff, your heirs or descendants will have no such qualms at all.

GROSS: Do you ever pick out things that you want for yourself when you're supposed to be putting everything in the dumpster?

MURPHY: No (Laughter). But we get - movers get offered things all the time. In fact, so here are the - here's the four things that movers get offered most commonly - pianos, hot tubs...

GROSS: (Laughter).

MURPHY: ...backyard trampolines and pool tables.

GROSS: Why?

MURPHY: Every mover I know could have six or seven of these things if they wanted to have them.

GROSS: Why are those the things?

MURPHY: Because they're big and bulky. And depending on where they're moving to, they may or may not have room. They put it on Craigslist. They priced it wrong. And on moving day, it's still there. And then at that point, they just want to get rid of it.

GROSS: They don't say, I'll leave it for the next family; they'll love having it?

MURPHY: (Laughter) We do that too because usually we're not taking the hot tub or the backyard trampoline.

GROSS: Right, OK. Let me reintroduce you here. If you're just joining us, my guest is Finn Murphy, and he's a long-haul trucker. He moves people long distances and moves all their possessions to their new home. Now he's written a memoir about it called "The Long Haul: A Trucker's Tales Of Life On The Road." We're going to take a short break, then we'll be right back. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF THE BEATLES SONG "A DAY IN THE LIFE (REMIX)")

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. And if you're just joining us, my guest is Finn Murphy. He's written a new memoir about being a long-haul trucker. Basically it's like a huge moving van. He deals with high-end customers who are moving to distant locations. His memoir is called "The Long Haul: A Trucker's Tales Of Life On The Road."

What's one of the strangest things that you've had to move?

MURPHY: Probably a collection of Chinese gravestones. This gentleman that I was moving - he had eight of them, and he had purchased them somewhere. Each one was worth $80,000. He had a gallery set up in the center of this giant house - this 16,000-square-foot house in Aspen, Colo. And he had pedestals custom made. And it was our job to put the gravestones on each of the pedestals. And each one weighed 600 pounds or so. And this shipper - he treated us so badly. He - this is a house with 11 bathrooms, and he had gotten a port-a-potty for us to use during the move that was outside.

GROSS: Wow.

MURPHY: And he kept going...

GROSS: He's entrusting you with this, you know, fortune's worth of stuff, and he won't even let you use his bathroom or one of his bathrooms.

MURPHY: Right, yeah. That's how it works sometimes.

GROSS: But if he's disrespecting you that way, how are you supposed to respect his possessions?

MURPHY: Well, fortunately, movers and restaurant workers have some sort of retaliatory measures at hand.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Uh-oh. Here we go.

MURPHY: So we didn't say anything to him. And he kept going down into town and bringing back food for himself and his wife and people and - anyway, we were starving, and we were using the port-a-potty. And we were putting - uncrating these gravestones. And one of the things that I had done in my not-so-stellar college career was I had taken a semester of Chinese. So I knew the orientation of the Chinese characters, and I was pretty sure that my shipper didn't. So when we installed his gravestones, we put them in upside down.

GROSS: (Laughter).

MURPHY: And he couldn't tell the difference. So we were really looking forward to the day when he was going to have a cocktail party and show off his gravestones. And somebody who was - understood Chinese would tell the philistine that he had them all wrong.

GROSS: How does a house even support so many 600-pound gravestones?

MURPHY: Well, he had an Olympic pool in the basement, so I imagine it was made...

GROSS: Oh, my gosh, OK (laughter).

MURPHY: Oh, yeah, this - I get to see some pretty amazing places.

GROSS: Yeah, OK. So what's the view like when you're riding high up in the cab of a truck and all the other cars, especially the compact cars like me, are so far below you?

MURPHY: So what people don't seem to understand is that I can see everything. And people tend to think that their automobile is anonymous. And I find that really amusing. So you've got this vehicle with windows all around it and a license plate on it. And you're out in public. It's, like, the least anonymous thing that you could be doing. But the behavior that people perform...

GROSS: (Laughter).

MURPHY: ...Inside their vehicles makes it look like they don't think anybody can see. Well, I can see everything. So I know what everybody's doing in their cars. And, you know, Americans - we're pretty good drivers in general. The worst drivers are in - around D.C. And the best drivers for some reason are in Michigan. I'm not quite sure what that is. But if Americans would just drive while they're driving instead of doing something else and driving, that would be a lot better for everybody.

And here's - so here's what most people are doing in their cars that I can see. They're eating. They're drinking, either a legal or an illegal beverage. They're putting on makeup, texting obviously, disciplining kids in the back seat. That's a big one. But most of the time that I can see through the body language is people are working on their relationship with the person in the passenger seat. And sometimes that could be romantic and sweet, which is a nice little treat. And then most of the time it's conflict.

GROSS: I thought you were going to say people are picking their noses.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: I honestly thought that. And I thought something else you were going to say that has to do with body fluids. So, you know...

MURPHY: This is a family show, Terry.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: I know. So you've seen that, too. You're just not mentioning it.

MURPHY: I haven't seen anybody actually eliminating fluids in a car, no.

GROSS: All right.

MURPHY: I haven't seen that. I have seen some romantic moments.

GROSS: Yes, OK. So you write that you've worked with people who are suspicious of your diction and demeanor. And white-collar people wonder what a guy like you who looks and sounds like them is doing driving a truck and moving furniture for a living. So people are suspicious of you or surprised on both ends. The truck drivers are suspicious of your diction and demeanor. And the people who you're moving wonder, like, what an educated guy like you is doing moving furniture for a living. So how does it feel to have both - what's my question?

MURPHY: I'll toss in if you want.

GROSS: What's my question, Finn?

MURPHY: I think your question is...

GROSS: (Laughter) You tell me.

MURPHY: ...Is how - I love being an enigma like that. It's very satisfying to me. I'm sort of a typical, middle child, black sheep of the family kind of guy. So if I'm confusing people, I like that a lot. And I do confuse people because when I go into the truck stop or something like that, I don't speak with a Southern accent. And, you know, I don't change the way that - the kind of person that I am.

DAVIES: Finn Murphy's book is the "The Long Haul." After a break, he'll tell us how you park and 18-wheeler and what he would do when he felt drowsy. We'll remember actor Burt Reynolds who died yesterday. And linguist Geoff Nunberg reflects on when we call a lie a lie. I'm Dave Davies, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF BROKEN SOCIAL SCENE SONG, "7/4 (SHORELINE)")

DAVIES: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Dave Davies in for Terry Gross. We're listening to Terry's interview recorded in February with Finn Murphy, author of the memoir "The Long Haul: A Trucker's Tale Of Life On The Road." His specialty now is hauling the possessions of corporate executives and their families moving to new homes for their new jobs. He's been driving a truck since the late 1970s. He grew up in suburban Connecticut and dropped out of college, much to his parents' dismay, to become a truck driver.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

GROSS: You don't mention this in the book, but your father was John Cullen Murphy, who drew the popular newspaper comic strip "Prince Valiant." And you seemed to want to get as far away from his life as possible. But it sounds like being the son of a comic strip artist would be so great. And in fact I interviewed your brother recently who wrote a memoir about being the son (laughter) of a comic book strip artist. And it seemed to be great for him. So what were you rebelling against within your family?

MURPHY: So it was great having my father as a commercial illustrator. In fact, he had a studio behind our house, so my father was always home. When we came back from school or whatever, he was right there. My father was one of the most gentle and affable people anybody has ever - you know, would ever have encountered. On the other hand, my mother is very much of a Irish matriarch. And with eight children to keep into line and make sure that we all got fed and clothed and had - took care of our various activities, it was a very strict household from my mother's end. And she was the one who managed the day to day of keeping eight children in order.

GROSS: So how did it go over with your parents when you told them you were dropping out of college at the end of your junior year to become a long-distance trucker?

MURPHY: So yeah, back to my father for a moment - probably the one regret of his life was that he was not able to go to college. His father died when he was 19. My father had to support his family. And all he ever wanted to do was to go to college. So for him, it was a huge thing to be able to have all eight of his children attend college, graduate from college and have some kind of a professional career.

So when I said I was going to go and work for North American Van Lines and not return back to school, that hit him in a place where he felt vulnerable and a place that he felt that I was being very ungrateful, which I was being very ungrateful. And I hurt my parents. I hurt my family. And we didn't speak for a couple of years. It was actually - it was a little over two years that I never - I didn't even speak to my parents.

GROSS: So you write, (reading) many young male neurotics find out early that hard labor is salve for an overactive mind. Running up and down staircases for hours on end, carrying dressers and refrigerators and pianos was to me a relief from stress. Hard work temporarily shut down the constant movie running in my brain that looped around in an endless cacophony of other people's expectations, obligations, guilt, anger and rebellion. So, like, you had to get out of your head through physical work?

MURPHY: Yes, I did. That's a really good sentence by the way, isn't it?

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Yeah. It's pretty good. Did you work on that a long time?

MURPHY: No, I didn't actually. It just rolled right off the page. But yes, one of the great things about manual labor and especially for - if anyone who's done continual manual labor over a long period of time, there's a zone in there that is very, very satisfying. There's a zone about working with men. There's something tribal about it. There's something elemental about it. This is how I think we used to live for hundreds of thousands of years. And I really enjoy that part of it. Also, it's a meritocracy. You're - on a moving van, you're either doing the work and capable of doing the work, or you're not capable of doing the work.

So there's nothing about who you are, where you come from, what language you speak. All of that is gone on a moving van, and life is very simple. And the work is - has some specialized knowledge required to it, but the work is also very simple. And our days are, you know, 10 to 14 hours loading a truck or unloading a truck with a group of men and a few women now. There's a few women in the moving industry now, but it's still, you know, mostly men. It's still mostly immigrants. It's people who don't speak English in many, many cases. And you don't need language when you have work because the work is the language.

GROSS: You stopped driving for about 10 years. You don't say in the book what you did during those 10 years. Can you give us a sense of what your life was like in the 10 years that you stopped driving?

MURPHY: Yes. So I was working for North American Van Lines, and I was getting basically burnt out. And one of the things that I had always intended to do when I left college was to save some money and go into business for myself. And that was really one of the goals. I didn't just quit college and just, you know, sort of flip the bird to everybody. I actually had some kind of a plan. And back then, you could - I could make a lot of money. I was making a hundred thousand dollars a year in 1981 as a mover.

So I saved a bunch of money. I bought an import company importing - you know those beautiful fisherman's sweaters from Ireland? I used to import those into the United States from the west of Ireland. And I got into the other parts of the textile business and then started importing cashmere sweaters from Scotland and had a very successful business on Nantucket Island in Massachusetts.

GROSS: And then you went back into trucking again.

MURPHY: (Laughter).

GROSS: So what happened?

MURPHY: So I was on - living on Nantucket Island as a high-profile businessman and citizen and community activist. I was actually chairman of the county commissioners on Nantucket. I was a police commissioner. I was the airport commissioner. I was on the board of the chamber of commerce. I was a successful person, married, living in a small town. And, well, what happened is I got into a relationship with a woman who wasn't my wife. And my life exploded. Or probably more accurately, I took a match to my life and blew it to pieces. And so Nantucket is not a place where that kind of thing is going to be unnoticed or uncommented upon. And so then I went back out on the road because I didn't know what to do - completely lost. And you know what? There's a lot of us out there - a lot of drivers who are like that. And I knew I'd have plenty of company.

GROSS: Well, changing the subject for a second, I have to say a paragraph I particularly enjoyed in your memoir has to do with how you listen to a lot of public radio when you're driving in your truck (laughter) and that you know a lot of other truckers who listen to public radio, too - and so my personal thanks for that and for a very nice mention of me and our show. But I love that one Klan member from Georgia calls NPR U.S. Jews and girls report.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: That's pretty funny. And as you said, yeah, he might say that, but he listens.

MURPHY: Yeah. He probably doesn't have the mug, though.

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: We don't know for sure, though, do we?

MURPHY: I don't.

GROSS: (Laughter) That would great if he did. So just a couple of questions before we wrap up - you can't just pull into any parking lot when you're driving an 18-wheeler. So it's kind of personal. (Laughter) It's kind of private, but what do you do for pit stops, like, when you need the bathroom? Do you have one of those jars, one of those bottles for truckers?

(LAUGHTER)

GROSS: Is that OK for me to ask you that?

MURPHY: (Laughter) That's fine. So here's - so the trucker staple here is an empty Gatorade bottle. And if you go into a truck stop parking lot on a summer afternoon...

GROSS: Oh, no (laughter).

MURPHY: ...You'll see legions of flattened Gatorade bottles all over the parking lot, and that will provide an interesting olfactory experience. So yeah, there's that. I try to get out and be a little more civilized about it, which I can do most of the time. But you're right about trucks. So my truck is 73 feet long with a 53-foot trailer. So I cannot go many, many places. And this brings up an ambivalence for me because I talk in the book about how much I dislike suburban sprawl and auto-dependent development and all those kinds of things. But with a 73-foot truck, I actually rely on that kind of sprawl. I need to be in the Walmart parking lot or in the truck stop. So it's kind of difficult.

GROSS: What do you do when you're starting to fall asleep at the wheel?

MURPHY: It's really easy for me. So for you four-wheeler drivers out there, if you start getting that fluttering-of-the-eyelid thing, then you're - it's really time - it's actually past time to pull over. So see if you can remember that. And when I get that, I pull over. But the easy thing for me is I've got a double-bed in the back with 600-count sheets and a feather duvet, and it's tucked in with hospital corners. And I've got a climate control system. And I can take a 15- or 20-minute nap. And actually, I sleep better in the sleeper than I sleep anywhere. I can also pull my truck over and probably - if you pull a car over on the side of the highway, you're probably going to get hassled, or somebody's going to wonder what you're doing. But trucks - they just get completely left alone. So I'll take a 20-minute trucker nap right back in my comfy little bed and get back on the road.

GROSS: All right. Good luck to you with your writing and your driving, and thank you so much for talking with us. It's really been fun.

MURPHY: Thank you, Terry. I'm thrilled to be here.

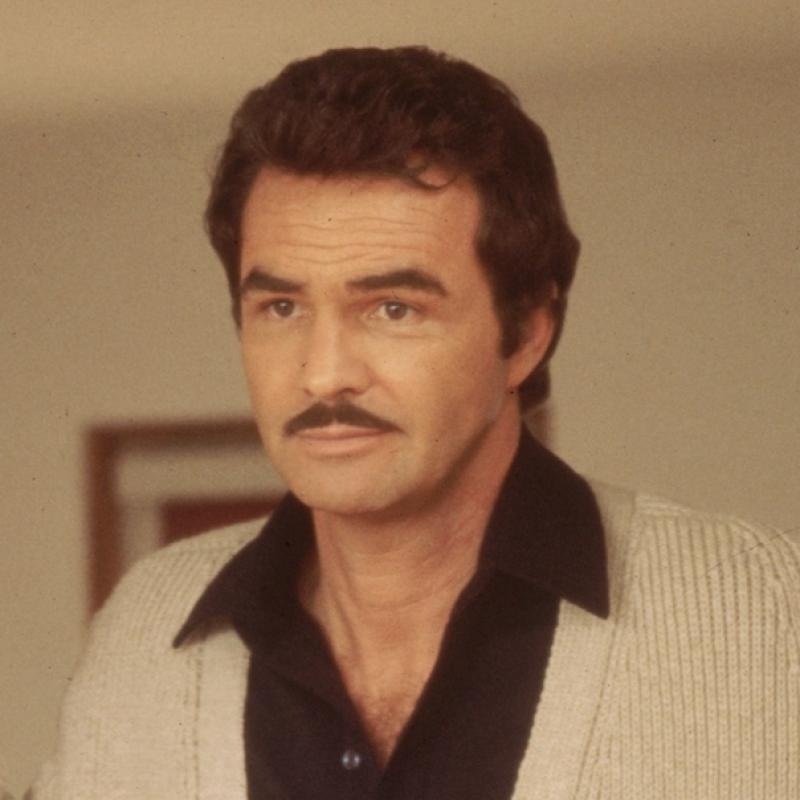

DAVIES: Finn Murphy's book is "The Long Haul: A Trucker's Tale Of Life On The Road," which is now out in paperback. Coming up, we'll hear an excerpt of Terry's 1994 interview with actor Burt Reynolds, who died yesterday at the age of 82. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF JERRY GRANELLI'S "NEVER GONNA BREAK MY FAITH")

DAVE DAVIES, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. TV and film star Burt Reynolds died yesterday in Jupiter, Fla., from a heart attack. He was 82. Reynolds appeared in a hundred films. Many, he joked, were so bad they were shown in prisons and on airplanes because no one could leave. Reynolds began acting in the '50s, but his career really took off when he became a regular on the TV talk show circuit in the '70s, cracking jokes with Johnny Carson and Merv Griffin. Among his films are "Deliverance," "The Longest Yard," "Smokey And The Bandit" and "Cannonball Run." In 2005, he got his only Oscar nomination for his role in the film "Boogie Nights."

Reynolds had a volatile temper and an eventful life. He was in a serious car accident that ended his college football career and suffered a shattered jaw in the '80s when he was hit with a chair doing a stunt for a movie. That led to an addiction to painkillers. Reynolds also had a series of Hollywood marriages and romances with Judy Carne, Dinah Shore, Sally Field and Loni Anderson.

Terry spoke to Burt Reynolds in 1994 when he'd written a memoir called "My Life." She asked him what it was like to grow up the son of a sheriff in a small Florida town.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

BURT REYNOLDS: Well, it's like being a preacher's son or a sheriff's son or whatever. I mean, you go one of two ways. You're either a little angel, or you're crazy. And I thought crazy was the best choice of the two. I was always in trouble. And I didn't want anybody to think that, you know, because I happened to be the son of that I could get away with things. And, boy, he let me know right away that I didn't.

TERRY GROSS, BYLINE: Did he punish you a lot when you were crazy?

REYNOLDS: Yes. I mean, he double punished. I mean, I was arrested once for fighting with about four guys. And they put us all in jail. And he came in and he said, your father's here; you can go home; your father's here; you can go home. Came to me and said, your father didn't show up. And I stayed there for four nights.

GROSS: (Laughter).

REYNOLDS: And he threw every drunk he arrested on top of me. I was always doing something that wasn't - you know, first of all, you have to understand that I don't respect anyone as much as I respect him. I don't - I never met a man in my life that I love more. But he was the kind of a man when he came in a room, all the oxygen left except for, you know, whatever he breathed. And he was 6-foot-4. And he was a very imposing, strong-willed man. And I spent most of my life - we have a saying in the South. No man is a man until his father tells him he isn't. And mine never did, which is why I was a little crazy until I was - well, till I had my son. Then I had to be an adult.

GROSS: I want to ask you about one of your most acclaimed films. And I'm thinking of "Deliverance." You were...

REYNOLDS: You could almost say only acclaimed film. But I was only in I think maybe two really acclaimed films, "Deliverance" and "The Longest Yard" and maybe "Starting Over" because it was nominated for an Emmy award, the picture was. But "Deliverance" was an extraordinary film in the sense that it was these four actors - I don't think you could get four actors who would do what we did.

GROSS: Well, you especially - you were almost killed...

REYNOLDS: Yes.

GROSS: ...In a waterfall scene. Why don't you describe the scene which apparently none of the stunt people even wanted to do?

REYNOLDS: No, they - well, they would be - they'd be - said, you know, you're too crazy. Go away. You know, and I was crazy. But we had a - we could stop the water. We had a dam that we had control over. And it was a place called Tallulah Gorge, which - Tallulah Bankhead actually was born there and was named after this gorge. And it was about 85 feet down. And they sent a dummy over. And Boorman looked at it - John Boorman, the director - and rightly so said, it looks like a dummy. And I said to Boorman, I can do that.

And so they put - they stopped the water, and I said, give me a spike, a mountain climbing spike. I went out in the middle of the river and drove the spike in, and I put a rope around it. And I said, now, when the water comes out, I'll - it'll come around me, see. And I'll put my hand up and wave, and that's when I'm going to let go so you can roll the cameras. And then I'll go down there. I'll hit that rock, and then I'll spin off to the left. And then I'll do a flip, and then I'll land down there. And they all went, right. You know, we've got four cameras. And I heard them letting the water go.

And I looked back, and coming at me was this tidal wave. And away I went. And I didn't go anywhere I told him I was going. I went wherever the water wanted me to go. But I - the first rock I hit, my tailbone cracked. Then I did turn a flip, which was what I said I would do, but I didn't do it on purpose. Then I landed in what they call a hydrofoil. Well, a hydrofoil - you can't swim out of it. You have to swim to the bottom, and then it kind of spits you out. And I had been told that. And I remembered it, thank God. And I went to the bottom.

What they don't tell you is that that spits you out like shooting a torpedo out of a submarine about 70 miles an hour. And I went over the falls a 30-some-year-old guy in the best shape of anybody and came up 150 yards down the river totally nude and about 78 years of age, could hardly walk and had hit every rock, you know, along the way going 70 miles an hour, it seemed. And they all thought I had drowned. I mean, they said, there's a nude old man limping this way. But we've got to concentrate on getting Burt out of this hole, you know?

GROSS: Well, what happened to all of your clothes? Were they shorn off by the rocks?

REYNOLDS: They just vanished. I mean, it was - that's how fast and how strong the water was. And the next day, I went to the rushes with everybody, very anxious to see my exciting stunt. And we looked at it. And I said to Boorman, how's it look? And he said, like a dummy going over the falls.

GROSS: Did it really look like that to you?

REYNOLDS: Not to me. It looked like a dummy but a different kind.

GROSS: (Laughter).

REYNOLDS: But it was an extraordinary stunt to me.

DAVIES: Burt Reynolds speaking with Terry Gross in 1994. Reynolds died yesterday. He was 82. Coming up, linguist Geoff Nunberg ponders the difference between lies and falsehoods. This is FRESH AIR.

DAVE DAVIES, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. We feel surrounded by mendacity and deception these days, whether in political discourse or the online forums we visit. Our linguist Geoff Nunberg has been thinking about when we label a lie a lie or call it something else.

GEOFF NUNBERG, BYLINE: In his essay on liars, Montaigne famously wrote that the truth has a single face while its opposite has 100,000 faces. That disproportion is reflected in the English dictionary. We have only a handful of words to describe statements that correspond to reality, like correct and accurate. In fact, we don't even have a single word that means tell the truth, which is probably to our credit. But we have a vast vocabulary to describe all the way statements can depart from reality. And it's gotten a considerable workout over the last couple of years.

Every news cycle seems to bring a new claim from the White House or elsewhere that cries out for correction and sends editors and journalists to their thesauruses, as politics makes linguists of us all. Should they simply qualify the statement itself? And if so, should it be called false or questionable, spurious or bogus, misleading or baseless? Or should they directly challenge the speaker's sincerity and use the charged word lie?

The establishment media have been pondering that question at length. A few of them, like the New York Times, allow themselves to use lie more or less sparingly. But a great many others have consigned the word to the verba non grata file. They argue that lie implies an intent to deceive, and you can't objectively observe what somebody believes. In fact, sometimes they don't even know themselves. And even when someone's deceptive intent is obvious, calling a statement a lie is invariably antagonistic. You can't use the word dispassionately. As the Oxford English Dictionary puts it, lie is a violent expression of moral reprobation. But that's exactly why a lot of people demand that journalists call out lies whenever they see them.

The New York Times Maggie Haberman provoked a torrent of indignant tweets earlier this year when she described two of the president's statements as demonstrable falsehoods rather than lies. One journalist tweeted that falsehood should be removed from the dictionary - adding let's call a lie a lie. The linguist Dennis Baron says that calling lies falsehoods is pulling your punch. But not so fast - it's true that falsehood can sometimes be just a decorous synonym for a lie. But often it's just the word we want. It's an old-fashioned word with the fusty ring of the pulpit, and we rarely use it in everyday speech. But falsehood can have a moral weight of its own - especially when we are more concerned about the effects of what someone says than about whether they were being insincere about it.

The birther story is a quintessential falsehood - a narrative feeding on malice and ignorance, which took on an independent life as it passed from one person to the next. In that sense of the word, a falsehood does its work whether the person spreading it believes it or not. Modern communication technologies have created powerful resources for publicizing and circulating falsehoods. They permeate social media where we call them by other names. They're misinformation, propaganda or fake news. Those words don't apply to individual statements but to concerted efforts to shape public opinion. They're relatively recent words. They only date from the rise of the mass media. And their meanings have been disputed ever since.

Even so, the engineers at Facebook find themselves in the unenviable position of trying to reduce them to rules that they can hand to their moderators, to police what they rather wistfully describe as the Facebook community. Facebook says they'll take down content that's doing harm or attacking individuals. But they won't block something just because it's false. Their argument recalls the one that journalists give for their reluctance to call some statement a lie. How can you tell whether people believe what they're saying or not? In a recent interview with Recode's Kara Swisher, Mark Zuckerberg explained why they wouldn't remove the pages of Holocaust deniers. It's hard to impugn intent and to understand the intent, he said. There are things that different people get wrong. I don't think that they're intentionally getting it wrong. He said that Facebook might demote the post in the news feed, but they won't just remove it.

A lot of people found those remarks distressing. Shortly after the interview, the Anne Frank Center announced that they had gathered 150,000 signatures on a petition calling on Facebook to remove Holocaust-denial pages. The fact is that saying the Holocaust didn't happen isn't simply getting your facts wrong, like confusing Benicio Del Toro with Antonio Banderas or saying that carrots help you see in the dark. Whoever utters it is spreading a malignant falsehood whether they're devious people or merely deluded ones. As the tech entrepreneur and social activist Mitch Kapor said, the intent of Holocaust deniers is not the sole standard of judgment. It's the impact that matters.

In the current climate, it's easy to get fixated on mendacity in high places. But bear in mind that the word truth has two antonyms. Sometimes we contrast truth with lies and sometimes truth with falsehoods. We need both words. Even transparent or trivialize erode our trust in one another. And when lies are more consequential, they can be amplified into pervasive falsehoods that distort the way people see the world.

DAVIES: Geoff Nunberg is a linguist at the University of California Berkeley School of Information. On Monday's show, James Beard Award-winning chef Jose Andres tells us about preparing millions of meals for people in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. Arriving in San Juan days after the hurricane, he stayed for months and recruited an army of volunteers. Andres wants governments and nonprofits to rethink how we feed people in a natural disaster. His new memoir is "We Fed An Island." Hope you can join us.

Fresh AIR's executive producer is Danny Miller. Our technical director and engineer is Audrey Bentham, with additional engineering support from Joyce Lieberman and Julian Herzfeld Our associate producer for digital media is Molly Seavy-Nesper. Roberta Shorrock directs the show. For Terry Gross, I'm Dave Davies.

(SOUNDBITE OF CHEO FELICIANO SONG, "ANACAONA")

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.