Contributor

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on October 25, 2001

Transcript

DATE October 25, 2001 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

Interview: George Chakiris, Rita Moreno and Marni Nixon discuss

the film "West Side Story"

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

On this edition, we celebrate the 40th anniversary of the film "West Side

Story," the great musical about two rival street gangs in New York: the Jets,

a white gang, and the Sharks, a Puerto Rican gang. The film was adapted from

the Broadway musical, which opened in 1957. The music was composed by Leonard

Bernstein, with lyrics by Stephen Sondheim. From the soundtrack of the film,

here's the Jets' song.

(Soundbite of Jets' song)

Unidentified Man #1: (Singing) When you're a Jet, you're a Jet all the way

from your first cigarette to your last dying day. When you're a Jet, let 'em

do what they can. You've got brothers around. You're a family man. You're

never alone. You're never disconnected. You're home with your own when

company's expected. You're well protected. Then you are set with a capital

J, which you'll never forget till they cart you away. When you're a Jet, you

stay a Jet.

Now I know Tony like I know me, and I guarantee you can count on him.

Unidentified Man #2: In, out, let's get cracking.

Unidentified Man #3: Where are you going to find Bernardo?

Unidentified Man #2: It ain't safe to go and be in our territory.

Unidentified Man #1: There's a dance tonight at the gym.

Unidentified Man #2: Yeah, but the gym's neutral territory.

Unidentified Man #1: A-Rab, I'm gonna make nice with him. I'm only gonna

challenge him.

Unidentified Man #3: Right, daddy-o.

Unidentified Man #1: So listen. Everybody dress up sweet and sharp. Meet

Tony and me at the dance after 10, and walk tall!

Unidentified Man #2: We always walk tall. We're Jets! The greatest!

Unidentified Man #1: (Singing) When you're a Jet, you're the top cat in town.

You're the gold medal kid with a heavyweight crown. When you're a Jet, you're

the swingingest thing. Little boy, you're a man. Little man, you're a king.

Group of Men: (Singing) The Jets are in here, our cylinder's are clickin'.

The shots will stay clear 'cause every Puerto Rican's a lousy chicken. Here

come the Jets like a bat out of hell. Someone gets in our way, someone don't

feel so well. Here come the Jets...

GROSS: The cast of the movie "West Side Story" recently celebrated the 40th

anniversary with a reunion and screening at Radio City Music Hall. This

Saturday night, Turner Classic Movies will show the movie, along with

interviews with some of the film's stars. A little later on, we'll meet Marni

Nixon, who dubbed Natalie Wood's singing voice for the film, and Rita Moreno,

who played Anita, the girlfriend of Bernardo, the leader of the Sharks.

First, we'll hear from the actor who played Bernardo, George Chakiris. He won

an Academy Award for his performance. Here he is in the war council scene

planning a rumble with the Jets.

(Soundbite of "West Side Story")

Unidentified Man #1: We challenge you to a rumble, all out, once and for all,

except...

Mr. GEORGE CHAKIRIS (Actor): On what terms?

Unidentified Man #1: Whatever terms you're calling. You've crossed the line

once too often.

Mr. CHAKIRIS: You started it.

Unidentified Man #1: Who jumped Baby John this afternoon?

Mr. CHAKIRIS: Who jumped me the first day I moved here?

Unidentified Man #2: Who asked you to move here?

Mr. CHAKIRIS: Who asked you?

Unidentified Man #2: (Unintelligible)

Unidentified Man #3: Back where you came from!

Unidentified Man #1: Spicks.

Mr. CHAKIRIS: Mick.

Unidentified Man #1: What?

GROSS: Before George Chakiris was cast in the film as the leader of the

Sharks, he starred in the London production of the show in the role of Riff,

the leader of the Jets. Chakiris is of Greek descent. I asked him what he

had to do to make himself appear Puerto Rican for the film.

Mr. CHAKIRIS: Well, one of the things they did to us, I'm very pale as a

person, so they darkened us, of course, considerably. In fact, I remember

when we started shooting the prologue, the very first take out on the streets

of New York there, Jerry had them come up and say, `No, I think he needs to be

a little darker,' so they made me darker still. So that was one thing that

certainly had to be done. And the other thing was the accent, which I think

was subtle--I hope anyway. And as I recall, we took Rita as our guide, so to

speak, to make sure that we were sort of on track with that.

GROSS: Well, one of the glorious and silliest thing about "West Side Story"

is the singing and dancing gang members. What did Jerome Robbins tell you

about the choreography and the kind of choreography he wanted for the gang

members, and why would they be dancing in the street?

Mr. CHAKIRIS: Well, it was a musical.

GROSS: Exactly. Compelling reason.

Mr. CHAKIRIS: But one of the things that I think Jerry did so

brilliantly--and he was, God knows, a brilliant man, and I think genius is not

an overblown word to use very directly in describing Jerry--but the way the

movement is introduced in the prologue of the film, when you first start to

see guys dance on the streets of New York, you know, it's done with a very

subtle kind of move, which is not really a dance move. And then there is

another move, you know. And...

GROSS: Yeah. What's happening is the Jets are walking along the street...

Mr. CHAKIRIS: Right.

GROSS: ...and one of them will kind of like jump up in a dance, really, move,

and then keep walking and then...

Mr. CHAKIRIS: Or just put his arms out, or...

GROSS: Yeah, or just put his arms out.

Mr. CHAKIRIS: ...very subtle stuff that eventually explodes, if you like,

into dance.

GROSS: Exactly.

Mr. CHAKIRIS: But we're introduced to it, I think, in a way that allows us,

at least I think, to accept it...

GROSS: Mm-hmm.

Mr. CHAKIRIS: ...and not think, `Oh, my God, don't they look silly dancing

in the street,' you know.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. CHAKIRIS: The theater version started the same way, well, in the sense

that they don't start dancing right off the bat. They build up to it. And

again, that building up allows it to, quote, unquote, "explode" into the way

they feel about their turf and the way they own the street and how the street

feels to them and the neighborhood feels to them; it's theirs.

GROSS: Now you actually shot the movie version of "West Side Story" on the

streets of New York, yes?

Mr. CHAKIRIS: Right, 68th and Amsterdam was one of the locations; that's

where Lincoln Center now stands. And the other location was a playground,

which is still there, 110th Street and 2nd Avenue. Those were the two

locations.

GROSS: Let's talk about the rumble scene, and this is the scene where the two

gangs rumble in a school yard, and it's like part dance and part a

choreographed fight.

Mr. CHAKIRIS: Right.

GROSS: But there's more dance in it than your average choreographed fight in

an action film.

Mr. CHAKIRIS: Yes. Mm-hmm.

GROSS: So everything in it is really quite stylized. Can you talk a little

bit about the choreography of it and learning it and what it's like to stab

and to be stabbed in this choreographed kind of way?

Mr. CHAKIRIS: Yeah. You know what I'd like to go back to in answering your

question was doing the theater version of the rumble because, of course, we

had to do it eight times a week. I would say it was staged rather than

choreographed because there are no dance moves, per se, really, in the rumble.

There are moves that make sense for a knife fight. And I remember--and you

don't really notice this particular move, which I thought was such a wonderful

move. You don't notice it as well, I think, in the film as I remember the way

it felt, at least, in the stage version. And I, as Riff, had to do this to

Bernardo in the stage version. It's hard to describe, but I run toward him; I

sort of invert myself so that I get a scissor kind of grip with my legs around

his legs, and I bring him down to his knees and then bring up the knife like

I'm going to stab him, and then somebody pulls me off.

But these were kind of gymnastic things, if you like, although I'm not a

gymnast at all. But, again, I think the difference in the rumble is it's

staged, but I would not say it's choreographed because there are not dance

moves in it.

GROSS: Did the actors playing the members of the rival gangs, the Jets and

the Sharks, mingle on the set, and were you advised to keep separately, as if

you really were Jets and Sharks?

Mr. CHAKIRIS: It wasn't the same as the theater version. Now I think in the

theater version, although, again, I was not there for the creation of it,

Jerry Robbins made it clear on the first day of rehearsal that he wanted the

Sharks to stay over there, the Jets to stay over there, not have lunch

together, not socialize with each other. He encouraged that what he really

needed was to create the tension and the danger that is vital to the piece.

So that was very much there. Even for us when we were re-creating the piece

for the London production, when it came time to the movie, he absolutely

wanted that same tension and danger, but he eased up on that particular

aspect, but it was still there.

GROSS: Was it helpful, in the London cast, to keep the Jets and Sharks

separate? Was that helpful to you?

Mr. CHAKIRIS: It was, and I think one of the reasons it was--I have seen

productions of "West Side Story," not many, in the theater, where the danger

is not there, and I think Jerry's means of getting that danger there--that is,

by keeping us separate--definitely did help. I had never acted in my life.

I'd been a chorus dancer. I mean, I wanted to be an actor; I just didn't know

how to get there. So it was helpful. And it also made us go further in our

own imaginations as to how to keep that feeling alive on the stage. And being

younger people, I think Jerry--this was little cutting to the chase. You

know, he knew how to make it happen.

GROSS: Now I've read that some of the actors who tested for parts in the film

adaptation of "West Side Story" include Tony Perkins, Warren Beatty, Bobby

Darin, Burt Reynolds, Richard Chamberlain and Troy Donahue.

Mr. CHAKIRIS: And Robert Redford.

GROSS: And Robert Redford? Really?

Mr. CHAKIRIS: Yeah. I heard that...

GROSS: For which part?

Mr. CHAKIRIS: I don't know, but I know I've heard that. I don't know if I

heard it from Bob Wise, but I think so.

GROSS: Did you know that all those other people had tested?

Mr. CHAKIRIS: Had no idea at all, no. And, again, going back to this thing

when we were doing it in the theater, never dreaming you'd get--it just never

entered our minds that we'd ever be part of this, it was a tremendous thrill

and surprise because we were getting news from Los Angeles about, you know,

big stars testing--or maybe not testing, but being considered. I think two of

the names that I remember hearing--I think I'm correct--one was Elizabeth

Taylor and one was Elvis Presley. I don't know if those were, in fact, real

considerations or not. It was just part of the bits of things...

GROSS: Right. Interesting.

Mr. CHAKIRIS: ...in newspapers that would be put on the bulletin board for

us to see at the stage door.

GROSS: Now you won an Academy Award for your performance as Bernardo.

Mr. CHAKIRIS: Right.

GROSS: How did it change your career to get the Academy Award?

Mr. CHAKIRIS: Well, before that, I didn't have a career. I mean, I was

doing well enough, I suppose, really. But what it did was it opened doors for

the remainder--and still does, oddly enough. It still does. But it changed

everything for me, certainly.

GROSS: Were you typecast as Puerto Rican after "West Side Story," even though

you're not Puerto Rican?

Mr. CHAKIRIS: Yes, I was. You know, the two things I--the only time I ever

worked in Los Angeles on anything was "West Side Story." Every other film I

made, anything else that I did was always somewhere else. It was in England;

it was in France; it was in Italy, Australia. I never got to work in the

States again. But, you know, there were the guest appearances on, you know,

things like "Murder, She Wrote" that many of us did. And the ones that always

came up for me--and I chose not to do them--I would always be offered the part

of, A, someone who was Latin or someone who was a choreographer. So they

couldn't get away from the Puerto Rican dancing thing, you know, for me. And

that--yeah, so I was typecast, but thank God there were other places to go.

GROSS: George Chakiris won an Oscar for his performance as Bernardo in the

film "West Side Story."

Coming up, we meet Rita Moreno, who played his girlfriend Anita. This is

FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: We're celebrating the 40th anniversary of the film "West Side Story."

My guests are Rita Moreno and Marni Nixon. Nixon dubbed Natalie Wood's

singing part in "West Side Story." Nixon also did the singing for Deborah

Kerr in the film "The King and I."

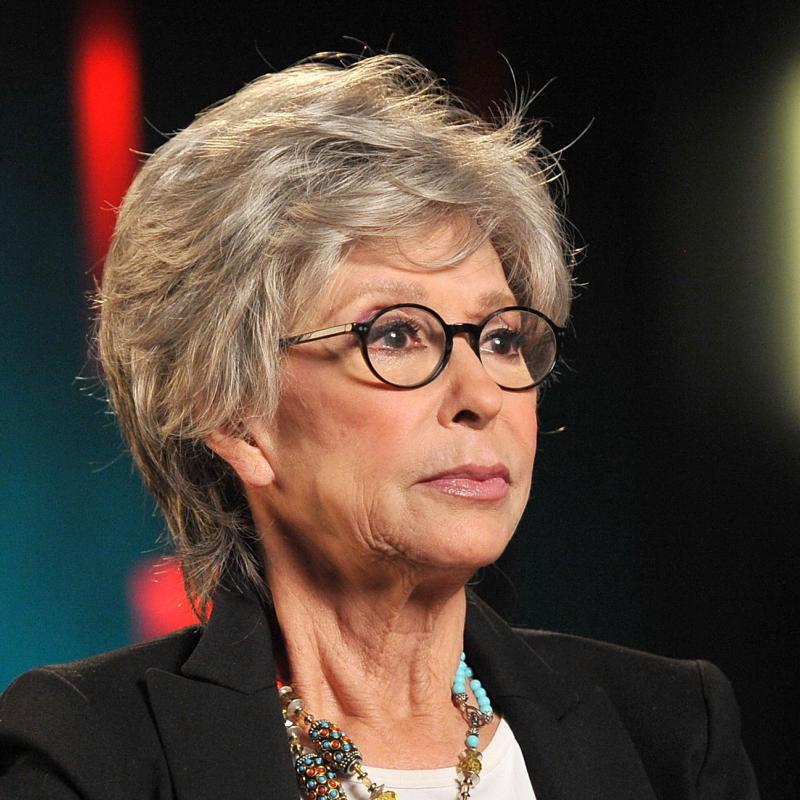

Rita Moreno won an Oscar for her performance as Anita, the girlfriend of

Bernardo, the leader of the Puerto Rican gang, the Sharks. Moreno now is one

of the stars of the HBO prison series "Oz." She was one of the few actors in

the film "West Side Story" who played a Puerto Rican and was actually from

Puerto Rico.

Ms. RITA MORENO (Actress): The reason was that there simply weren't enough

Hispanic--forget Puerto Rican--Hispanic male and female dancers at the time

who could do the kind of professional job that was needed for Jerome Robbins'

choreography, which is, you might have noticed, extremely complex and very

difficult. There just weren't any. The reason there weren't any, I am

surmising, is that a lot of Latin kids, Latino kids, in those days didn't have

the money to take those kind of classes. They were a lot like, in the way,

the street dancers of years later, the kids who danced on their backs and all

that kind of stuff, who had talent, but didn't have the training. So, as a

result, the Sharks--gosh, there were just a few of us, really, who were truly

Latino, who were able to get the part.

GROSS: Did you have to do anything to look more, act more or sound more

Puerto Rican?

Ms. MORENO: They made me use an accent, which I wasn't thrilled about

because a lot of us, obviously, don't have them. The thing that really

bothered me the most is that they put the same very muddy, dark-colored makeup

on every Shark girl and boy, and that really made me very upset. And I tried

to get that changed, and I said, `Look at us. We're all, you know, many, many

different colors. Some of us are very white, some of us are olive-skinned,

some of us actually have black blood, some of us are Taino Indian,' which is

the original Puerto Rican. And nobody paid attention, and that was that. I

had no choice in the matter, but I was not happy.

And when I saw the film recently and saw George Chakiris, this beautiful guy,

Greek guy, who looked like he had fallen into a bucket of mud, I just started

to giggle.

GROSS: Now, Marni Nixon, you dubbed the singing for Natalie Wood. Did she

know when she got the part that she was going to be dubbed, that she wouldn't

be singing herself?

Ms. MARNI NIXON: No, I think the problem always during the picture was that

I think it was very unclear; that she didn't know how much of her voice could

be used. They didn't tell her that gradually--I guess as they worked with

her, that maybe it wasn't going to be good enough because they were afraid to

upset her. And it created an atmosphere of--I felt very uneasy. And when we

recorded the songs actually, we recorded them--they said they were going to

record them with her doing the complete songs, with maybe there were

combinations of me doing the high notes within those complete recordings of

her's, and then they would record me doing the complete songs. And then they

said they were going to combine those electronically later on, which I knew

was not really possible to do.

I think they created a monster, really, in her because they--she would listen

to her takes, and she didn't know--it's very hard to know whether you're good

or bad and not really being a singer. And these huge speakers that magnified

any kind of discrepancy--and, anyway, they would tell her afterwards, `Oh,

Natalie, it is just wonderful, absolutely wonderful.'

GROSS: Oh, that's so awful.

Ms. NIXON: And then they would turn to me and wink, and I just felt like I

wanted to cringe.

GROSS: What did you think of her takes? Did you think her singing was good?

Did you think it needed to be dubbed?

Ms. NIXON: Well, you know, I can't even remember, except that I knew that

they probably would all have to be thrown out. I think what happens is that

when you're not really trained in music theater or in opera, that you can sing

your own things in your tempo and your own songs and in your own way, in your

own key. But when you're doing a Bernstein score, it's written like an opera.

I mean, you have to have the rhythm exactly right, and she had to acquire an

accent, which then I had to try to acquire because I had to be her.

GROSS: I'm getting...

Ms. MORENO: I heard her recordings. I heard her recordings because--well,

we all had to have stuff like that at home, and actually she had a very bad

voice. She wasn't a singer.

GROSS: Right.

Ms. MORENO: And it's not even fair to judge her on her singing because she

wasn't a singer. She maintained and obviously insisted that she at least get

first crack at it, which I suppose is fair. I think what was terrible is what

Marni just related...

Ms. NIXON: Yes, terrible.

Ms. MORENO: ...because, as you know, it would...

Ms. NIXON: Oh, that...

Ms. MORENO: ...she would finish a take, and they'd carry on as though

Amelita Galli-Curci had just, you know, come back. That's dreadful.

GROSS: So what was her reaction when she was told, `Well, it's going to be

dubbed by Marni Nixon. Your voice isn't going to be used in the songs'?

Ms. NIXON: Well, I think, from what I've heard--now this is only secondhand.

GROSS: You weren't there.

Ms. NIXON: I only learned it through the musical powers that be, and they

said that she was just absolutely furious and stomped out of the studio in a

total rage. But I guess they knew that that would happen or--anyway, there

was nothing she could do about it legally. So then, actually, I never really

saw her after that, except months later after the picture had been released.

So I didn't have any relationship with her after that, so I never knew--and

she certainly didn't take it out on me.

GROSS: Rita Moreno, do you remember Natalie Wood's reaction when she found

out that she was being dubbed?

Ms. MORENO: Only what I heard, which is that she was deeply, deeply

disappointed, and it's certainly understandable given the way in which they

handled it. I think she really believed it was going to be her voice, mostly

her voice, with Marni doing, as she says, the tough notes, the hard notes, the

long notes. And it must have been horrible for her. It's so unfair. And I'm

no fan of hers, but I don't think--I think they dealt with it very, very

poorly.

GROSS: You're not a fan of hers?

Ms. NIXON: No, I don't think she was right for the role. She didn't think

she was right for the role. It's one of the reasons that she was not terribly

friendly to the cast and not because--she was never, ever rude. Let me make

that very clear. But she was aloof. And the reason I realize now that she

was so aloof is that she felt so out of her element, which indeed she was.

But the cast took it in a different way, and it's a shame because it made for

a surprising amount of walking on eggs and tension around the set. I mean, it

wasn't--I can't say it was horribly stressed. We had a terrific time. But

there was always one person missing, and that was Natalie.

GROSS: Rita Moreno and Marni Nixon will be back in the second half of the

show, as we continue our 40th anniversary tribute to the film "West Side

Story." The film will be shown on Turner Classic Movies Saturday night, along

with interviews with some of the film's stars.

I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

Group of Girls: (Singing) I like to be in America. OK by me in America.

Everything's free in America.

Unidentified Man #4: For a small fee in America.

(Announcements)

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Coming up, we continue our 40th anniversary celebration of the film

"West Side Story" with Rita Moreno, who won an Oscar for her performance as

Anita, and Marni Nixon, who dubbed the singing for Natalie Wood.

Also, linguist Geoff Nunberg considers the lyrics of our national anthem.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross back with Rita Moreno and Marni

Nixon. We're celebrating the 40th anniversary of the film "West Side Story."

Rita Moreno won an Oscar for her performance as Anita, the girlfriend of the

leader of a Puerto Rican gang, the Sharks. Marni Nixon dubbed the singing

voice for Natalie Wood. Wood played Maria, a Puerto Rican girl who falls in

love with a former member of the white gang, the Jets. When Natalie Wood was

making the movie, she sang her part and didn't know that her songs would later

be overdubbed.

Well, Marni Nixon, when you were doing the singing, it must have been

complicated since Natalie Wood thought she was singing for real, you know.

She was lip-synching to her own recording, and then, well, did you have to

sing in such a way as to match her lip movements?

Ms. NIXON: Well, usually, the process is that it's always the actress that

has to come in and has the job of mouthing to her track or to anybody's track.

And when she had filmed it to her track, the problem was also that she wasn't

in synch with her own track. And I said, `Well, how am I supposed to fix it

up if her lips are already not in synch with the orchestra?' And they said,

`Well, you'll figure out a way.' And so that's the hardest way. I mean, it's

so much better if it's prerecorded and decided and then she has to do it and

then maybe you'd just fix up a few little spots, but this was--in every single

song practically, it was that way.

Ms. MORENO: It's also a question of feeling, how that person feels when

they're singing those particular lines.

Ms. NIXON: Yes.

Ms. MORENO: I was not able to sing "A Boy Like That." I was dubbed by

another person for "A Boy Like That" for a very simple reason--not because I

can't sing but because at the time, I was practically a coloratura which is a

very, very high-ranging voice. And I could not for the life of me--and

believe, me I tried--I could not reach the low notes in the beginning of the

song which starts (singing) `A boy like that, he'll kill your brother.' And

then it goes up very high to (singing) `very smart, Maria, very smart.' And I

couldn't reach those low notes, so they finally said, `Well, we're going to

have to find somebody for you,' which, of course, broke my heart. And they

brought in a woman--at the time, a girl--named Betty Wand who sang for me.

And let me tell you how difficult that is. I sat in the control room trying

to tell her--because I started this conversation about feeling, how Anita was

feeling at that time, but Betty Wand was a singer, she was not an actress who

sang. And she just couldn't get it the way I wanted it. I want it...

GROSS: Oh, that's terrible.

Ms. MORENO: Oh, it's heartbreaking. It's heartbreaking...

GROSS: Oh.

Ms. MORENO: ...because I wanted to sound--it should have almost been a growl,

(singing) `A boy like that,' you know, barely sung. And she ended up

sounding--and whenever I hear it, my stomach knots up because she sounded

almost like a cliche Mexican. She was going (singing) `A boy like that will

kill your brother.' I wouldn't dream of ever singing the song that way.

GROSS: Oh.

Ms. MORENO: And, by the way, I'm not making fun of her. That's the only

thing she was able to do, and no one was able to help her, even though I was

there to do it any differently because we must have done take after take

after take after take trying to get her to do it the way I wanted it done and

the way, you know, it should have been done.

GROSS: Well, Rita Moreno, what was it like for you to be singing this duet

knowing you were being dubbed by somebody whose performance you didn't really

like, singing this duet with Natalie Wood? Because she's singing `I have a

love and it's all that I have. Right or wrong, what else can I do?' And

she's being dubbed and she doesn't know she's being dubbed, so, you know, what

a kind of odd circumstance to be doing this.

Ms. MORENO: And...

GROSS: Just to clarify what's happening in the scene for listeners who might

not have seen the movie. Natalie Wood, Maria's boyfriend, Tony, has just

killed Anita's boyfriend at a rumble and he didn't mean to do it. He didn't

want to do it, but he did it to revenge the murder of his best friend. And so

you, Rita Moreno as Anita, is saying, you know, `A boy like that who killed

your brother. You know, how can you be in love with him?' And Natalie Wood

is saying, `I have a love and it's all that I have.' So that's...

Ms. MORENO: But Anita's not only saying that, she understands when she comes

into the bedroom that this girl, Maria, who was a virgin till then...

GROSS: Right.

Ms. MORENO: ...has slept with her boyfriend's murderer because she runs to

the window looks out...

GROSS: Yeah.

Ms. MORENO: ...Anita does and sees him running away from the building. So

it's just so many things going on, not only that she just found out that

Bernardo has been killed by Tony, but that Maria, Maria of all people, has

just bedded with this young man.

GROSS: Marni Nixon, you dubbed Natalie Woods' part on this duet. What's you

experience of this duet?

Ms. NIXON: You know, I have no recollection, except it might have been one of

the duets that--and maybe Rita would know--that was planned for me to do all

along. So maybe she was singing to my voice during the filming. I'd

forgotten that completely.

Ms. MORENO: You know what, Marni? I think your voice was on that one...

Ms. NIXON: Yeah, I think it was all me.

Ms. MORENO: ...because if had been Natalie, it would have been even more

difficult to do.

Ms. NIXON: Well, come to think of it, I don't think she could have even

stretched into that. I think it was just the musical directors approved of

it. I think I heard her sing it in the rehearsal studio and got a feeling of

what it was supposed to be. And then I just recorded it. And then she had to

approve of that, and I don't know--I guess she did because I don't think we

had to take it over, but it really wasn't in a duet form. I mean, I never saw

Rita in the recording studio at all. So we didn't really do a duet together.

GROSS: Well, now I have to play this duet that we've been talking so much

about. So...

Ms. MORENO: Now you're going to hear a very Mexican girl.

GROSS: Right. So I imagine on screen we're seeing Natalie Wood and Rita

Moreno but what we're hearing in this duet is Marni Nixon and...

GROSS and Ms. MORENO: (In unison) ...Betty Wand.

(Soundbite of music)

Ms. NIXON: (Singing) Oh, no, Anita, no. Anita, no. It isn't true, not for

me. It's true for you, not for me. And in your words and in my head, I know

they're smart, but my heart, Anita, but my heart knows it's wrong. You should

know better. You were in love or so you said. You should know better.

Ms. BETTY WAND: (Singing) I have a love, and it's all that I have. Right or

wrong, what else can I do? I love him. I'm his and everything he is, I am

too...

GROSS: A duet from "West Side Story" with the voices of Betty Wand and Marni

Nixon. And my guests are Rita Moreno and Marni Nixon. Marni Nixon did the

dubbing for Natalie Wood; Rita Moreno played Anita in the movie.

I'm wondering after the movie was shot, did Natalie Wood not want anyone to

know that you, Marni Nixon, had dubbed her voice, and how did you feel about

how much credit you should get? And then, Rita Moreno, I'm wondering how you

felt about people finding out that in one song in your duet, that your voice

was dubbed? Did you not want people to know that?

Ms. MORENO: Well, no, I didn't want them to know I was. At the time, I was

very, very--so embarrassed because it sort of seemed to cast a shadow on the

rest of the stuff that I did sing, and I got over that. I mean, that's just

ridiculous, but I'll tell you what is disconcerting and I'm going to find out

about it soon. Apparently, I think it's Columbia Records has Betty Wand's

name on all of the stuff that I did, too. And that's made me very, very

unhappy.

GROSS: My guests are Rita Moreno and Marni Nixon. We'll talk more about

"West Side Story" after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: It's the 40th anniversary of the film "West Side Story." My guests

are Rita Moreno, who won an Oscar for her performance as Anita, and Marni

Nixon, who dubbed the songs for Natalie Wood.

Ms. MORENO: Yeah.

GROSS: Rita Moreno, I want to ask you about another scene. There's a scene

toward the end of the movie after your boyfriend Bernardo has been stabbed.

Maria, the Natalie Wood character, asks you to send a message to her

boyfriend, Tony. And this is right after the "I Have A Love" duet.

Ms. MORENO: Right.

GROSS: And so you go to...

Ms. MORENO: The candy store.

GROSS: ...the candy store to give a message to the owner there, and all the

Jets are hanging out there. And they start taunting you and the implication

is that they've raped you, too. I think that's the implication.

Ms. MORENO: Oh, yes. Yes, if it had been...

GROSS: Yeah.

Ms. MORENO: ...done a few years ago, that's what would have happened.

GROSS: Right. But it's all kind of stylized and choreographed. Can you talk

about that scene?

Ms. MORENO: Gee, I'm glad you brought that up because that was a seminal

scene for me. Some interesting and personal emotional pond scum came to the

surface. We rehearsed that number, as we did with everything in that movie,

for weeks. And then we got to the shooting which took, I would say, about

seven days. And at some point, having the boys constantly cursing me out and

throwing me around and calling me things like Spick and Garlic Mouth and

Pierced Ear apparently opened up some wounds that I thought had been healed

years and years and years before then. And I remember that at that point--and

I think it was in the middle of shooting some part of that scene, I stopped

and I sat down at the stool of the candy counter, put my head on my arms and

started to sob and cry and I could not stop. I must have cried for about 45

minutes and there was no consoling me. I was inconsolable.

And it's funny. As I speak of it, I start getting tears in my eyes. And the

boys came to me and said, `Oh, Rita, please, you know we love you. You know

we love you. Please don't cry. Please stop. Oh, the audience is going to

hate us.' And I couldn't stop. And finally Bob Wise called lunch and, you

know, I calmed down obviously after lunch and we got it all done, but there is

a huge piece of my soul in that scene. It's all of the terrible things that

happened to me--not like that, but it was symbolic of all of the terrible

things that happened to me when I was younger that apparently just inundated

my soul and seared my soul and I was as surprised as anybody.

GROSS: When you were able to start shooting the film again, do you feel like

that personal connection deepened your performance or did it get in the way of

it because it was so upsetting?

Ms. MORENO: No. No, it didn't get in the way. I think it deepened it, and

by the time we got to the part of the scene where Doc, the candy store owner,

comes in and stops the symbolic rape and I go to the door and say, `Don't you

touch me,' because I think they were saying something like, `Don't let her get

away.' And somebody puts their hand on my shoulder and I turn around and say,

`Don't you touch me.' Wow! That was filled with every terrible anger that I

have ever experienced in my life, that line. It didn't get in the way.

GROSS: Can you talk a little bit about the choreography that Jerry Robbins

worked out for the rape scene?

Ms. MORENO: Jerry had an ability which is rare even now to choreograph for

character. In other words, any step that Anita might do, say in "America" or

in the mombo at the gym, was not a step that he would ever have dreamed of

giving to some other character on the other side, for instance, to a Jet girl.

And he worked that out with us. He was a meticulous crazy man. He was

meticulous with respect to what he wanted. The problem was he didn't always

know exactly what he wanted. He just wanted it to be perfect. And Jerry had

several versions of each section of each dance, so that, for instance, if you

were rehearsing "America" with him, he would, after you did one version, say,

`OK. Let me see version B of section II.' So you were really learning

anywhere from two to three other dances beside the original one. That's how

he worked. And he would watch it and watch it and watch and then say, `OK.

Now let me go back to section I and do version A of that.' He wanted to get

the very best he could out of each section of these dances. And that's how

the rape scene also happened. It was a question of throwing me around, and

when they would throw me around, when someone would grab my blouse to try to

tear it off, then somebody would lift up my skirts to humiliate me--all that

kind of stuff was very, very planned.

GROSS: Any thoughts on the fact that the 40th anniversary of "West Side

Story" shot on location in Manhattan coincides with the transformation of

Manhattan after the World Trade Center attacks?

Ms. NIXON: Oh, I'd like to say that one of the thrills was seeing that

opening shot of the skyline of New York City pre-World Trade Center and having

the audience suddenly--the relevancy of where we were at that moment and of

seeing New York in this wonderful helicopter shot and having people suddenly

burst into applause of cheers, it was really about the relevancy of the story

but the relevancy of, `Here we are here.' And all of the current thoughts

were piled on top of that. That, to me, was exciting also.

Ms. MORENO: It was immensely resonant. It was really--the audience just

went crazy with that opening shot because it was...

GROSS: This was at the Radio City Music Hall 40th anniversary screening.

Ms. MORENO: Radio City Music Hall just two weeks ago.

GROSS: Yeah.

Ms. MORENO: Yeah. Yeah. It was amazing because they--it's as though

they--it was a Manhattan they wanted desperately to see.

GROSS: Right. Well, thank you so much for giving us "West Side Story." It's

such a wonderful film and thank you so much for your performances and thank

you for talking with us.

Ms. MORENO: Great to be with you.

Ms. NIXON: It's been a treat.

GROSS: Rita Moreno won an Oscar for her performance as Anita in "West Side

Story." Marni Nixon dubbed the songs for Natalie Wood. Turner Classic Movies

will celebrate the 40th anniversary of the film Saturday night. They'll show

the film and feature interviews with some of the stars.

(Soundbite of music)

Ms. NIXON: (Singing) Anita is going to get her kicks tonight. We'll have our

private little mix tonight. You walking hot and tired, poor dear. Don't

matter if you're tired as long as he's near.

TONY: (Singing) Tonight, tonight won't just be any night. Tonight there will

be no morning star. Tonight, tonight, I'll see my love tonight. And for us,

stars will stop where they are.

Ms. NIXON: (Singing) Tony, the minutes seem like hours. The hours go so

slowly. And still the sky is light. Oh, moon, grow bright and make this

endless day, endless night...

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: Coming up, linguist Geoff Nunberg on the lyrics of the national

anthem. This is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Commentary: Alternative anthems that would be less militaristic

and easier for everyone to sing

TERRY GROSS, host:

The burst of patriotism following the September 11th attacks has everybody

rethinking the significance of American symbols, particularly "The

Star-Spangled Banner." Some people say the song is too militaristic. A

school board in Madison, Wisconsin, instructed schools to use only an

instrumental version. And just about everybody complains that the song is too

hard to sing, but our linguist Geoff Nunberg isn't sure about the

alternatives.

GEOFF NUNBERG:

If you ask me, "The Star-Spangled Banner" has gotten a bad rap. After all,

those rockets and bombs were coming from the British ships that were

bombarding Ft. McHenry as Francis Scott Key watched helplessly from the

harbor. The song celebrates America's surviving a foreign attack, not

launching one. Even so, I can understand why some people would as soon have

an anthem with no war images at all. And "The Star-Spangled Banner" does have

insurmountable musical deficiencies. It's fun to cheer at a baseball game

when a performer hits the high note on `land of the free,' but anthems ought

to be songs that everybody can sing in unison without requiring throat surgery

afterwards.

The reconsideration of the anthem has been in the air for a while. We seem to

redefine our national symbols every hundred years or so. Most of the present

apparatus of American patriotism was put in place around the turn of the 20th

century. The Pledge of Allegiance was composed in 1892 by Francis Belamy,

a Boston Socialist and Baptist minister. Actually, Belamy had originally

proposed having the pledge end with `liberty, justice and equality for all,'

but that was unacceptable to members of the Massachusetts Education Board who

were opposed to giving the women the vote. And it wasn't until 1916 that

President Wilson issued an executive order that made "The Star-Spangled

Banner" our official national anthem around the same time he proclaimed Flag

Day a national holiday.

In any case, people seem to feel it's time for a change. During the last few

weeks of the major-league season, baseball teams were playing "God Bless

America" at the seventh inning stretch and a lot of people were treating it as

if it were a real anthem, standing and removing their hats. I've always liked

that song, particularly when I imagine the setting that Irving Berlin intended

it for when he composed it in 1918, a Ziegfeld style production number for an

all-soldier musical review called "Yip, Yip, Yaphank." The song became famous

in 1939 when Kate Smith recorded it with lush strings and brass. It's

certainly the catchiest of all the contenders and it would be fitting for

America to have an anthem written on Tin Pan Alley, but we're not ready for

that yet.

The clear front runner for an anthem replacement is "America the Beautiful"

written back in 1893 by a Wellesley professor named Katherine Lee Bates.

Willie Nelson closed the all-star TV benefit on September 22nd by leading

everybody in singing the song. An ABC News correspondent, Lynn Sherr, has a

new book high on the best-seller lists with the title "America the Beautiful:

The Stirring True Story Behind Our Nation's Favorite Song." No question, it

is a likeable song. It may not be stirring like "Battle Hymn of the Republic"

which is the only patriotic song that America's produced that could go elbow

to elbow with the "Marseillaise" and "Deutscheland Uber Alles" if it came to a

showdown in Rich's Cafe. But "America the Beautiful" is a sweet little tune,

particularly when Ray Charles sings it. And it's a song you can join in on

without self-consciousness.

I can understand the appeal of the lyrics, too. It's partly that call for

coast-to-coast brotherhood, but mostly it's those pretty landscape pictures,

like a set of old chromolithograph postcards, but I'm troubled about the idea

of making the song our national anthem. Maybe it's the overblown language

with its contorted syntax and fulsome descriptions. You have to be wary of

any verses that have that many adjectives in them, particularly adjectives

like spacious, amber, purple and fruited. If we have to have adjectives, I'll

take free and brave.

This isn't just a stylistic quibble. That overwriting is a symptom of the

late 19th century sentimentalism about a vanishing rural America. It's easy

for modern Americans to sympathize with that, given our own concerns about the

threatened environment, but it puts the essence of the country far from the

daily lives that most of us live. When I was a kid in Manhattan, I remember

singing about purple mountains and waves of grain and thinking that America

must be a distant place somewhere out beyond New Jersey. And the sublime

landscape of the song doesn't have any more to do with a country that most of

us inhabit now, a land of spacious parking lots and amber traffic signals.

Of course, we all love purple mountains even if we aren't all fortunate enough

to see them out of our kitchen windows. But there's something reductive about

making our landscape the focus of our anthem. Any country can do that. The

Swiss sing about the Alps going bright with splendor. The Czechs sing about

water bubbling across the meadows and pine woods rustling amongst the crags.

The Brazilians sing about the sound of the sea and the light of heaven. And

the Syrian anthem begins with a remarkable entomological trope, `Syria's

plains are towers in the heights, a land resplendent with brilliant suns

almost like a sky centipede.' Anthems like that are particularly convenient

for nations that change their form of government every so often. Landscapes

don't have any politics, but the American experiment was supposed to be

different. Our patriotism is about a nation, not a land. No other country

tell its story as the history of a single regime. And some of that ought to

be up front in the anthem we sing.

I had a similar reaction to the administration's choice of the words Homeland

Security, rather than Domestic Security, to describe the new office headed by

Governor Ridge. I understand what they were getting at given the shock of the

attack on American soil, but even though Homeland is a perfectly good English

word, up to now, we've never used it to describe our own country. It has an

alien sound like the German word heimat. It's the word we use for peoples

who feel an ancestral connection to a particular plot of ground, whereas the

idea of America isn't that it's a place that people come from but a place that

they come to. The Germans and Kurds and Ukrainians have homelands. We just

have a nation and a flag.

GROSS: Geoffrey Nunberg is the author of the new book "The Way We Talk Now:

Commentaries on Language and Culture."

(Credits)

GROSS: We're listening to Irving Berlin. I'm Terry Gross.

Mr. IRVING BERLIN: (Singing) ...to the prairies, to the oceans white with

foam. God bless America, my home sweet home.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.