Other segments from the episode on August 2, 2005

Transcript

DATE March 2, 2005 ACCOUNT NUMBER N/A

TIME 12:00 Noon-1:00 PM AUDIENCE N/A

NETWORK NPR

PROGRAM Fresh Air

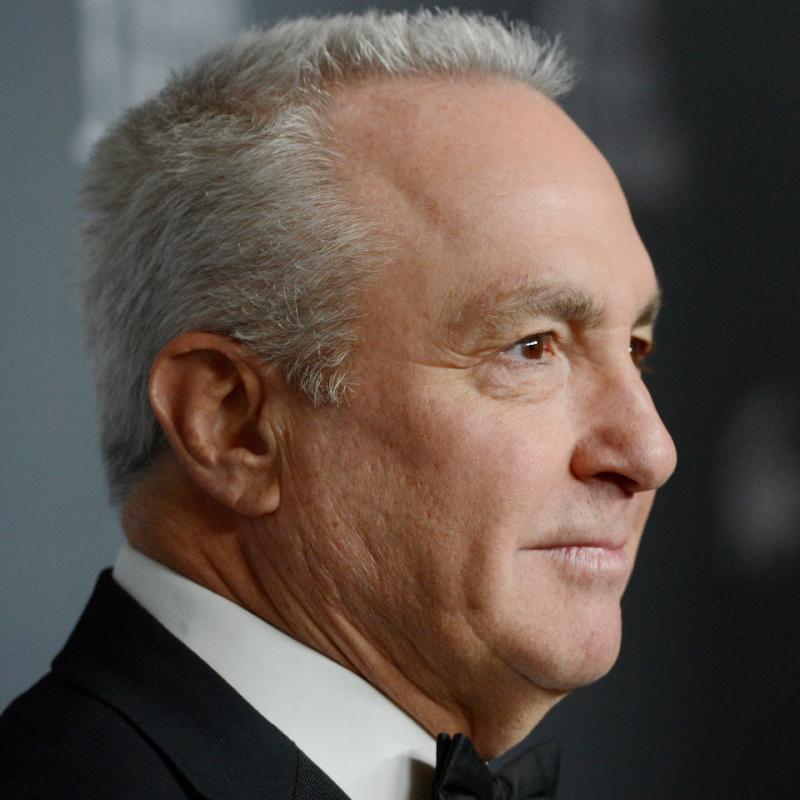

Interview: Lorne Michaels discusses his work as creator and

executive producer of "Saturday Night Live"

TERRY GROSS, host:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

"Saturday Night Live" is celebrating its 30th anniversary this year. My

guest, Lorne Michaels, created the show and is its executive producer. In

October, he received the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor in a ceremony at

the Kennedy Center. That ceremony will be shown as a 90-minute special this

evening on public television. It will feature clips, tributes and

performances. Lorne Michaels has been with "Saturday Night Live" for all but

five of its yeas, 1980 to '85. He produced many movies with performers who

got their start on the show. Here's a sampling of the past 30 years of

"Saturday Night Live."

(Soundbites from "Saturday Night Live")

Mr. LORNE MICHAELS (Producer, "Saturday Night Live"): Hi. I'm Lorne

Michaels, the producer of "Saturday Night."

Mr. CHEVY CHASE (As Himself): Good evening. I'm Chevy Chase, and you're

not.

Ms. GILDA RADNER (Cast Member): Now, a lot (pronounced wot) of people

thought my last (pronounced wast) program (pronounced pwogwam) was pretty

(pronounced pwetty) crummy (pronounced cwummy). Well, this one's truly

(pronounced truwy) crammed (pronounced cwammed) with clever (pronounced

cwever) revelations (pronounced revewations), rapport (pronounced wappor), and

repartee (pronounced wepatee).

Mr. STEVE MARTIN (Guest Host): We are two wild and crazy guys.

Unidentified Man: But no!

Mr. DAN AYKROYD (Cast Member): Jane, you ignorant slut.

Mr. EDDIE MURPHY (Cast Member): (Singing) I am dark and you are light.

Mr. JOE PISCOPO (Cast Member): (Singing) You are blind as a bat and I have

sight.

Mr. DANA CARVEY: (As Hanz) I'm Hanz.

Mr. KEVIN NEALON: (As Franz) And I'm Franz.

Mr. CARVEY and Mr. NEALON: (As Hanz and Franz; in unison) And we want to

pump you up.

MADONNA: Wayne, do you want to play truth or dare?

Mr. MIKE MYERS: (As Wayne) Truth or dare? With me? No way.

MADONNA: Way.

Mr. MYERS: (As Wayne) No way.

MADONNA: Way!

Mr. MYERS: (As Wayne) Excellent.

Mr. AL FRANKEN: (As Stuart Smalley) Because I' good enough, I'm smart enough,

and doggone it, people like me.

Mr. ADAM SANDLER (Cast Member): (Singing) Paul Newman's half Jewish and

Goldie Hawn's half too. Put them together, what fine-looking Jew.

Mr. CHRIS FARLEY (Cast Member): You're going to be doing a lot of

doobie-rolling when you're living in a van down by the river!

Ms. CHERI OTERI and Mr. WILL FERRELL: (As cheerleaders; in unison) U-G-L-Y,

you ain't got no alibi. You're ugly. You're ugly. Not cute! Whoa!

Mr. JIMMY FALLON (Cast Member): "Weekend Update," I'm Jimmy Fallon.

Ms. TINAY FEY (Cast Member): I'm Tina Fey. Good night and have a pleasant

tomorrow.

GROSS: "Saturday Night Live" is now the same age that Lorne Michaels was

when he created the show: 30. I spoke with him about how the show began.

Why was it important for you for "Saturday Night Live" to actually be live?

Mr. MICHAELS: I think the most important reason at the time was that we

wouldn't have to do a pilot. I had worked on enough pilots--three with Lily

Tomlin and with a bunch of other ones where when you're--the way people talk

themselves into things or the way that overthinking works is you say, `Well,

you know, when we're on the air, we can do different things, but now we just

have to get on the air.' And so you tend to want to please. And you tend to

do things that have already been done because that's the way you're guided.

And I thought if I could sort of get straight to the audience, if could just

do the show that I wanted to do and put it on the air, I thought there'd be an

audience for it.

And being live--the danger which I didn't fully comprehend at the time--I'd

done enough work on stage that I wasn't worried about that part. I just--and

also live audience, you know, I knew would be exciting. But there was--the

idea that the whole country would see it at the same time, including the

people at the network, who, while supportive, had bigger problems than what we

were doing in late night, you know. They had a prime-time schedule to worry

about. So we were left alone, and also we were in New York, which there

wasn't much production in. So we were kind of not on the radar or whatever

technology was dominant then.

GROSS: The way the legend goes, John Belushi had said to you, `I don't do

TV,' because he didn't like TV. And...

Mr. MICHAELS: Yeah. That's true.

GROSS: ...that you didn't get along, you know, at first, you know, there's

this kind of, like, chemical difference between the two.

Mr. MICHAELS: Well, he...

GROSS: So how come you hired him?

Mr. MICHAELS: Well, what happened was I was fairly serious about things

then, and I thought there was this little window, you know, that we could

maybe climb through and try and get this show on television in a way that was

pure. And so I wanted people who were completely committed. And I think

John, who I think was completely committed, came into our meeting and made

the point, which was a kind of backhanded compliment to me, that he didn't to

television, but that, you know, sort of what I was doing was the exception

that he was prepared to make. And I didn't want anybody who had any

ambivalence. So I just said, `Well, if you don't do television, that's all

right with me, because this is very much a television show.' Also, people

really looked down on television then. It was too big a medium, too mass a

medium, and I think people, you know--it was looked down on.

So--and I thought, having grown up watching television and loving

television--I thought, `Well, I don't want anybody who's, A, doing me a favor,

and, B, not completely committed to this. And I think John had really just

misspoken. And then--but it was just one of many, many meetings with lots of

different people.

GROSS: I want to read you something that Dan Aykroyd said in the book "Live

from New York," which is the book Tom Shales wrote, like a kind of oral

history of "Saturday Night Live." This has to do with the liveness of

"Saturday Night Live." He said...

Mr. MICHAELS: Right.

GROSS: ...`I once got mad and put a hole through a wall in Lorne's office.

I punched a whole in it because I was so mad at the way he would give us

last-minute changes before air. We would have to run down and give them to

the cue-card guys, and they would be going crazy and saying, "Are you

kidding? You want us to get this on?"'

So how do you deal with it when somebody in the cast puts a hole through your

wall? I mean, when their temper just gets so out of control that it actually

does physical damage?

Mr. MICHAELS: There was a fair amount of volatility in that period of the

show, but I think it was much more to do with all the changes that were

swirling around us and that sort of intoxicating brew of fame and celebrity

and money and power and all that, which was new to everyone there. It's not

that way now.

GROSS: People don't have tempers like that now?

Mr. MICHAELS: No. Well, you know, I can't vouch for everyone, but I'd say

that first period, or at least the period of around 1977, '78 was really the

period that Danny's talking about. Because up to that point, it had a very

strong, all-for-one, one-for-all quality. And I think that changed when the

opinion of the show changed.

GROSS: And then everybody got really famous and...

Ms. MICHAELS: Well, I mean, I think people--there was a little bit of a gold

rush quality to it. And I think it still was, and still is, physically

really hard to get that show on every week. I mean, we go from blank page to

on the air in six days. So--and with a different host each week, which is a

whole different set of writing problems. So writers and performers are

working side by side. There's designers, there's musicians, there's

filmmakers, there's a whole--and all of them tend to see and experience the

show through the prism of their own experience. If their piece got on, they

really liked the show last week. If their piece didn't get on, they didn't

think people really liked that show.

So it's a very intense process, and it can be bruising. It also is

exhilarating or else people wouldn't still be there doing it.

GROSS: You know, from reading about the show, it sounds like one of the

things that separates the first cast from subsequent casts is that the first

cast--people were very close, and then people were sleeping with each other.

So you have all these, like, professional competitions and jealousies mixed in

with, like, romantic competitions and jealousies. And that's, whoa, what a

brew.

Mr. MICHAELS: Yeah. I tend to think all that's a little blown...

GROSS: Overstated?

Mr. MICHAELS: Yeah.

GROSS: OK.

Mr. MICHAELS: But it made for excellent reading. And...

GROSS: Yes, it has.

Mr. MICHAELS: ...people are curious about it. And I think it's great. But

honestly, that wasn't what was the determining thing in the show. I think

everyone at the beginning of the show was unknown.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MICHAELS: Everyone.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MICHAELS: You know? And that meant the writers were unknown, the--I

mean, people had tiny followings, I suppose. But in terms of the national

level, no one was known. And then people became known and famous, and the

impact of it was, you now, overwhelming. And I think that altered people's

relationships, both with each other, their friendships, their, in some cases,

marriages. I think it was--you know, nobody had ever done it before. I think

it's much clearer now what sort of happens. And I think people know what it

is.

GROSS: My guest is Lorne Michaels, the creator and executive producer of

"Saturday Night Live." Tonight, PBS will broadcast the tribute to him that

was held at the Kennedy Center last October when he was awarded the Mark

Twain Prize for American Humor. We'll talk more after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Lorne Michaels. And he's the

creator and executive producer of "Saturday Night Live," which is celebrating

its 30th season this year.

You've said that the value system that was around at the beginning was as long

as people showed up on time and did their job, it was nobody's business what

they did in their bedroom or in their lives. And you said...

Mr. MICHAELS: Yeah.

GROSS: ...that value system turned out to be wrong.

Mr. MICHAELS: Well, I think that we were--what somebody older than me used

to refer to as my pseudo-egalitarian value system, or the way I ran the show

on...

GROSS: (Laughing) Yes.

Mr. MICHAELS: ...that level. But I think that you just don't know. It

starts with the core thing, which is the comedy. No one knows for sure what's

going to work, what's not going to work. So no one has--there are people who

are more experienced and therefore maybe listened to more. But at the end of

the day, if the apprentice writer has a better joke than the senior writer,

well, you have to go to the best joke, you have to go to the--you know,

the piece that involves building a ship, you know, that costs a lot of money

didn't play, but the piece where the person sat on a chair worked perfectly.

Well, you can't think of anything other than what's working. So people are

up and down in that value system all the time. And I think that turbulence,

which I like to think of as a sort of creative turbulence, is the defining

thing of the show. You're always--somebody who shouldn't emerges as the most

interesting thing that week because it's not ordained. It's just sort of you

go in, we go in always long, and until that audience comes in, you really

don't know what's going to work and what's not going to work.

And I think that what was going on in the '70s nationally was--I think there

was a strong fear of the government in the bedroom, I think there was a strong

fear of, you know, too much--you know, this is right after Watergate and the

Vietnam War. So I think there was a sort of new freedom, and we were testing

the limits of it. And I think that what I believed in was that you didn't

have responsibility--it wasn't your business, therefore it wasn't your

responsibility. And I think that turned out to be wrong. We just didn't know

enough.

GROSS: At some point, did you feel that you were the executive producer, so

it became your business to draw the line, even in people's personal lives, if

you felt it was interfering in some way with...

Mr. MICHAELS: Well, I think...

GROSS: ...your work on the air?

Mr. MICHAELS: In the first five years, I wasn't executive producer. I was

just producer.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MICHAELS: And that lofty title didn't exist. But I think that we were

all the same age. We were all friends. We all came from, you know,

approximately the same kind of place. And so I wouldn't have--in the same way

that when Chevy was leaving, he and I talked mostly as friends much more than

as producer-cast member. You know, whether or not it was the best thing for

him to move on was much more about what would be best for him than it was,

`Hey, come on,' you know. I think that we were--it was fraternal. And I

think as the years went by, I realized that more and more people looked to me

in a paternal role, which was shocking to me, 'cause I was 31.

And I think that when the same thing happened, for example, in the late '80s,

when Chris Farley got into trouble, at the very first sign of it, you know, he

was in rehab, whereas I think when John Belushi was getting into trouble, it

was hard to tell what was being on the cover of Newsweek and starring in

"Animal House" and what people's limits were, what people could handle or what

was--you know, 'cause it was all--and most of--I hope I'm not sounding

defensive on this, but I think most of what happened to people that was

destructive happened away from the show. In the case of John Belushi or the

case of Chris Farley, it happened years after they left the show. And I think

that the discipline of actually having to get that show on every week and of

letting down your fellow cast or the writers--there was just--always been too

much of a standard there and too much of a work ethic for people to screw up

there.

I think, you know, you finish a show at 1:00 in the morning, and there's an

enormous amount of adrenaline's gone through your system, and you're not ready

to go to sleep. And so people go to a party, and sometimes, people want to,

you know, obliterate the recent past or whatever. And I think, you know, it

was all sort of uncharted territory then. I think it's very, very

well-defined territory now, so I think people are just on the lookout for

stuff that's destructive or self-destructive.

GROSS: Well, you know, let me read you something that Bob Odenkirk, who had

been a writer on "Saturday Night Live," something that he said in...

Mr. MICHAELS: Yeah, go ahead, sure.

GROSS: ...the book "Live From New York." He says, `The greatest thing I

ever saw Lorne do was the way he wound up treating Chris Farley. I think

Lorne was determined not to have what happened to Belushi happen to Chris on

his watch, and it seemed to me that Lorne very seriously put it to Chris:

Every time Chris messed up, he had to get cleaned up before he could come back

on the show. Lorne really made Chris think about what he was doing, 'cause

the most important thing to Chris in the world was performing on that show.

That was the goal of his life, and Lorne knew it. And Lorne took it away from

him multiple times and forced him to go to rehab.'

Mr. MICHAELS: Yeah, I think that--well, it's so. But I think it was we just

knew more. You know, people would--you know, you'd see people in the '70s at

4:00 in the morning and they'd--you know, looked fine. Sometimes they

wouldn't look fine, but I don't think anybody ever saw anybody in trouble and

walked away from it. I think it was, you know, the next day, we had a show to

do, and people showed up. And that writers' meeting, which is on Monday, is

the same now as it was then, and people had to show up for it. And they had

to come prepared with an idea or two. So I think when people got away from

the show and they didn't have the structure and the discipline that the show

demanded of them, I think people got into trouble.

GROSS: Yeah. You know, I'm thinking that it sounds like you really

intervened in a positive way in Chris Farley's life when he was on the show.

And he...

Mr. MICHAELS: Yeah, but we did with John Belushi, too, multiple times.

GROSS: Right, right.

Mr. MICHAELS: It's--what I'm saying is that in--the show is and was a caring

environment. You know, it isn't like you want to see anybody get in trouble

or you're aware that anybody's in trouble.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MICHAELS: I think that the sheer fatigue of, in those days, four shows

in a month was, you know, people were bleary-eyed, people were exhausted, and

people were still going on and doing the show. And I think that people who

are used to that level of excitement, that level of whatever, when they

suddenly left, people tried to get it in different ways, I think.

GROSS: I have to say, it must be exhausting for your to have to oversee a

weekly live show and also take some responsibility for helping people who are

having trouble in the cast.

Mr. MICHAELS: Yeah. I think I'm certainly better prepared to do it now than

I was then. I think it was more--you know, it's glib to say we were making it

up as we went along, 'cause I think we were more sure-footed than that, but I

think there was so much we just didn't know, and then I think we didn't even

know that there was much of an audience reaction to the show till this first

summer, because we were always there. And New York City was moving along

quite well without us, so it was only when we got out into the country that

you realized people were actually watching the show, 'cause up to that point,

you sort of just hear about it from your friends or your family. But we had

no idea of the impact of it until, I think, Danny and John drove cross

country, you know, in that first break we had in July of '76, and they were

amazed that Pe--you know, John came back and said, `People really loved that

samurai thing I did.' And at that point, we hadn't--we sort of had a rule

about doing anything twice. And John was, you know, a prime proponent of that

rule, so he was sort of taken aback when people went, `When are you going to

do it again, you know?'

GROSS: Lorne Michaels is the creator and executive producer of "Saturday

Night Live." He'll be back in the second half of the show.

I'm Terry Gross, and this is FRESH AIR.

Let's hear a Chris Farley sketch, "The Christ Farley Show." Farley plays an

inept talk show host who's more a nervous fan than interviewer. In this

edition, his guest is Paul McCartney.

(Soundbite of "The Chris Farley Show" sketch from "Saturday Night Live")

Mr. CHRIS FARLEY: You remember when you were with The Beatles?

Mr. PAUL McCARTNEY: Sure. Sure.

Mr. FARLEY: That was awesome.

Mr. McCARTNEY: Yeah, it was, yeah.

Mr. FARLEY: OK. Oh, you remember when you went to Japan and, at the airport

they arrested you 'cause you had some pot, and made a hit in all the papers

and everything?

Mr. McCARTNEY: Well, to be honest, Chris, I'd kind of like to forget all

that.

Mr. FARLEY: Idiot! I feel so stupid! What a dumb question!

Mr. McCARTNEY: No, no, no, Chris. I get asked that all the time in

interviews. Maria Shriver asked the same question last week.

Mr. FARLEY: Really? Did you know that she's married to Arnold

Schwarzenegger?

Mr. McCARTNEY: Yeah, I've heard that. Yeah.

Mr. FARLEY: Did you see "Terminator?"

Mr. McCARTNEY: No, I missed that one.

Mr. FARLEY: It was a pretty awesome flick. OK. You remember when you were

with The Beatles and you were supposed to be dead, and there was all these

clues that, like, you'd play some song backwards and it'd say, like, `Paul is

dead,' and everyone thought that you were dead or something?

Mr. McCARTNEY: Yeah.

Mr. FARLEY: Yeah. That was just a hoax, right?

(Announcements)

GROSS: Coming up, more with Lorne Michaels, creator of "Saturday Night Live."

Also, we talk with Ed Levine about his new book "Pizza: A Slice of Heaven."

And David Bianculli reviews two shows created by David Milch: "NYPD Blue,"

which aired its final episode last night, and "Deadwood," which begins season

two this weekend on HBO.

(Soundbite of music)

GROSS: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross, back with Lorne Michaels, the

creator and executive producer of "Saturday Night Live," which is celebrating

its 30th anniversary this year. Tonight PBS will broadcast the tribute to

Michaels held at the Kennedy Center last October when he was given the Mark

Twain Prize for American Humor. Michaels insists he's not comfortable in

front of the camera, but he's made some memorable appearances on "Saturday

Night Live." Here he is in 1976 trying to convince The Beatles to reunite and

perform on the show.

(Soundbite of "Saturday Night Live")

Mr. MICHAELS: Now here it is, as you can see. Verifiably, it is a check

made out to you, The Beatles, for $3,000. All you have to do is sing three

Beatle tunes, "She Loves You (Yeah, Yeah, Yeah)." That's $1,000 right there.

You know the words. It'll be easy. Like I said, this is made out--this check

here is made out to The Beatles. You divide it any way you want. You want to

give Ringo less, that's up to you.

GROSS: Let's get back to my interview with Lorne Michaels.

Tom Shales says that although it's "Saturday Night Live," you hate ad-libbing

on the show. Why?

Mr. MICHAELS: Yeah. Well, I like spontaneity. I just--you know, we're a

written show, and because a lot of the people who appear on the show come from

an improvisational background, I think the fantasy or the illusion was created

somewhere in the '70s that it wasn't--you know, that people were making it up

as they went along, but that's--you can't set camera angles and cuts without,

you know, a sort of real discipline. And that's a script. And, you know,

it's a very strong writer's show. And people like Tina Fey, who's a, you

know, absolutely brilliant writer, is also a performer. You know, now can

she--as she's going, if something happens that she wasn't expecting, can she

react to it and say something that hadn't been, you know, written?

Absolutely. But by and large, what people are doing has been written, and the

control room is sort of following that same script.

GROSS: So many people on "Saturday Night Live" have gone on to not only be

incredibly successful in the show but to have incredible, you know, acting

careers, movie careers afterwards. A few people who were on "Saturday Night

Live" who had really incredible careers afterwards were almost invisible while

they were on "Saturday Night Live," and I'm thinking specifically of, like,

Robert Downey Jr. I just, like, don't even remember him when he was on

"Saturday Night Live."

Mr. MICHAELS: That was a very bumpy season. It was him and Anthony Michael

Hall and...

GROSS: Right, yeah.

Mr. MICHAELS: ...and Joan Cusack was in that group, too. No, that was a

cast that didn't show, and the person responsible for it not showing was me,

because I made all the choices. But I think that Randy Quaid was in it as

well. I think it was--you know, there were elements of that 1985 cast that

ended up being part of the--you know, the following year I brought in Dana

Carvey and Phil Hartman and Jan Hooks, and that group began to gel in a way

that it hadn't in the '85, '86 cast.

GROSS: Now in that '85 cast, did you think, like, `I lost it. I've lost my

talent for picking people'?

Mr. MICHAELS: Well, no. Yeah, it was a very tough time for me because, you

know, I did the first five years and then I left. And then when they were

going to cancel the show, Brandon Tartikoff asked me if I'd come back and do

it. And that was a sort of difficult decision for me, and when it looked like

it actually would be canceled--although I wouldn't have cared if it had been

canceled in any of the years between then, or if they'd canceled it when I

left in 1980, I think I would have been all right with that, too, then, but

somehow, turned out it mattered to me.

But when I came back in, I still had sort of--you know, I'd forgotten so much

how bruising it was, and I had very nice memories of what the first five years

were like. And of course, what had been a very--you know, `Saturday Night

Dead' appeared somewhere in the middle of the first season as a headline and

never went away. And so suddenly, to be beat up in 1985 by not having, you

know, it be the golden years, which, as I was living, were not called the

golden years, it took awhile to find a new way of doing the show. And I

think when Brandon was trying to get me to come back, he said, `You know,

like, in the '70s, you had to be the center of everything, of every sort of

creative decision, but, you know, you're older now, and you have to learn how

to delegate, and, you know, once you can delegate and, you know, give

authority to others and not be the center of things, then it'll be much

easier.' And then at the end of the '85 season, he said, `You can't delegate

anything. You have to be'--you know. And so I went back into it in a

different way, and it worked out.

GROSS: If you're just joining us, my guest is Lorne Michaels, and he's the

creator and executive producer of "Saturday Night Live," which is now

celebrating its 30th year on the air.

There's something I really want to ask you.

Mr. MICHAELS: Yeah.

GROSS: And this is kind of under the category `But enough about you. What

about me?'

Mr. MICHAELS: Uh-huh. sure.

GROSS: There was a sketch on "Saturday Night Live" that involved a public

radio cooking show, and one of the hosts was named Terry...

Mr. MICHAELS: Yeah.

GROSS: ...and some people, including members of my own family, have said to

me, `Does that sketch have anything to do with you?' And I say, `No, it has

absolutely nothing to do with me.' But let me ask you, do you know the

origins of where--or what inspired that sketch?

Mr. MICHAELS: Well, when it was Anna and Molly? I mean...

GROSS: Yes, exactly.

Mr. MICHAELS: I think it was just the--I think they were playing with the

dryness of--and the, you know, cheerfulness of a certain kind of approach to

what was--I don't know. I don't want to speak for them. I think they were

just fooling around, and I think it was meant in a complimentary way.

GROSS: Uh-huh. OK.

Mr. MICHAELS: I don't think you can get much more out of me on that, but I

think, as with all things, you know, part of it's drawn from something they

experienced or thought they could play.

GROSS: OK.

Mr. MICHAELS: And then after that--you know, by the time it reached Alec

Baldwin and `Schwetty balls'...

GROSS: Yeah.

Mr. MICHAELS: ...it was sort of a completely different kind of piece than

where it started at the beginning.

GROSS: Right.

Mr. MICHAELS: Yeah.

GROSS: Just one more thing. Did you ever want to be a full-time performer

yourself as opposed to, like, the behind-the-scenes guy? You've been on

"Saturday Night Live" as yourself many times.

Mr. MICHAELS: Yeah. No, and in the show I did in Canada, I was a performer.

And I think--when I was at college, I was in a bunch of plays, and

occasionally I would look over at the person who was talking to me on stage

and I'd realize they actually were that character, which was kind of--I

thought, `Oh, my God. They're completely lost in--you know, they are that

person.' I could never go that deep with it--that deep. So I thought the

best I could be, you know--OK, I didn't think I could be great at it. And

when I used to watch the show I did in Canada, I'd be in the editing room

editing myself, and I'd see myself before the slate, and I'd see myself

looking around, checking the lighting and looking at camera angles and all

that, and then the slate would happen and then there would be a big smile on

my face that suddenly happened, and I thought, `I'm not a natural at this.'

And I think that's fairly evident with today's interview, but I think, you

know...

GROSS: You're not comfortable talking?

Mr. MICHAELS: Yeah. I like to perform and I love being around performers,

and I love being around people that are funny.

GROSS: Well, Lorne Michaels, congratulations on...

Mr. MICHAELS: I have a good job, is my point. Yeah.

GROSS: Yeah. Congratulations on 30 years of "Saturday Night Live."

Mr. MICHAELS: Thank you.

GROSS: It's an incredible story. You've done incredible work. Thank you for

talking with us, at least about some of it.

Mr. MICHAELS: Oh, happy to. OK.

GROSS: Lorne Michaels is the creator and executive producer of "Saturday

Night Live." Tonight public television will broadcast the Kennedy Center

tribute to him at which he was given the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor.

Coming up, the perfect food: pizza. This is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Interview: Food writer Ed Levine talks about his book and about

the perfect food, pizza

TERRY GROSS, host:

Food writer Ed Levine describes pizza as the perfect food, so he doesn't seem

to have minded doing the research for his new book, "Pizza: A Slice of

Heaven." It tells the history of pizza, collects recipes and also collects

essays by many food critics discussing the burning issues surrounding pizza.

Levine is also the author of "New York Eats" and contributes to The New York

Times dining pages. He says there are many reasons why pizza is the perfect

food.

Mr. ED LEVINE (Author): It's the ultimate communal eating

experience--Right?--when you think about it. It's the food that we grew up

with that sort of emancipated us from our parents, right? I don't know about

you, but the first time I ever ate away from home by myself with my friends

was a slice of pizza. And I think a lot of people...

GROSS: You know, I've never thought of that before, but that is so true...

Mr. LEVINE: Right.

GROSS: ...because where I grew up in Brooklyn, there were pizza places--there

were, like, three great pizza places within two blocks. So even as a child, I

could walk with a friend to one of the pizza places and have lunch on our own.

Mr. LEVINE: And you were free at last. You know, you were free at last, and

you had two slices and a soda, and at the time...

GROSS: Absolutely.

Mr. LEVINE: I don't know how old you are, but, you know, for me, I'm 53.

The earliest memories I have of two slices and a soda, the slices were 15

cents, and the soda was a dime. So for 70 cents--and you could even leave a

really generous tip of 30 cents if you had a dollar. Now that's a pretty

fulfilling and cheap meal.

GROSS: Let's define our terms when we're talking about perfection. What kind

of crust do you like?

Mr. LEVINE: I like a crust that is made with either yeast sourdough starter,

salt, flour, water. Pizza crust is, at its heart, great bread, right? So it

should be the same things that go into great bread. And I like a crust that

has a veneer of crispness that gives way to tender, sort of internal bread

dough. So, you know, that first bite, you want to hit a little bit of

crispness, and then you want it to be tender, the same way when you bite into

a great baguette or a perfect piece of rye bread.

GROSS: And what about the surface, the cheese? What makes perfection there?

Mr. LEVINE: I like discrete areas of cheese and sauce. I like the

mozzarella to be fresh mozzarella, so it should look white. It shouldn't be

yellow, that aged mozzarella. That creepy yellow--that aged mozzarella is--I

don't like on pizza. And then I like sort of bubbles. I like the dough when

it's cooked in a very hot oven that's either fueled with wood or charcoal. I

like bubbles, you know, those little bubbles that you find in bread or on the

outside of pizza crust. I like those. You know, it means the pizza's going

to be crisp. It means the pizza's going to be light. And I don't like the

space-blanket school of pizza cheese, you know, like the raised pizza, you

know, where they put a half a pound of that weird cheese. You know, that's a

color not found in nature. I don't like that.

GROSS: And what about the sauce? What makes a good sauce?

Mr. LEVINE: My favorite kind of pizza sauce is as they serve it in Naples,

which is merely canned, strained, fresh tomatoes, preferably from Italy, from

San Marzano, but I've also had great California tomatoes. And I don't want

it to be cooked, and I don't necessarily even want any seasoning in it. I

like the taste of tomato, of simple tomato. I don't want it to taste like a

pasta sauce. If you cook the sauce that you put on the pizza, then it tends

to taste like a pasta sauce, and I like the simplicity of simple, canned,

strained tomatoes.

GROSS: Most places do use the pasta sauce, don't they?

Mr. LEVINE: Yeah, they do. It varies. It varies. A lot of places use

canned pizza sauce, also not a good thing. And most of the canned pizza

sauces are cooked. It's more forgiving. I'm sure it has a longer shelf life.

Some of the serious sort of artisanal pizza makers will use a cooked tomato

sauce on their Sicilian-style pizza and a fresh tomato sauce on their

Neapolitan-style pizza.

GROSS: You know how a lot of pizza makers--and this is particularly true in

the good old-fashioned pizzerias. They'll take the dough and they'll toss it

and twirl it in the air and they never drop it. What does that do for the

pizza dough?

Mr. LEVINE: You know, I'm not sure, because I'm not a practiced bread baker,

but most of the serious pizzaoa(ph) I know say that you don't really have to

toss the dough. I think it's to stretch the dough and to stretch it in an

even way. But I also think it became part, you know, theater for all the

pizzaoa in the country that had an open space, you know, where they could toss

the dough.

GROSS: Of course, so many restaurants serve those individual-size pizzas now,

and you can't very well toss those in the air.

Mr. LEVINE: No, exactly. And that's why, when you--in Naples, where pizza

in this culture was born in the 1830s, you never see them tossing, because

they only make one size of pizza. They only make the individual size pizza.

And this whole thing about larger pizzas only came into being when pizza moved

to America.

GROSS: You know, a lot of restaurants brag now that they have a brick oven

for their pizza. What does the brick oven get you?

Mr. LEVINE: Well, the brick oven reflects heat really well and allows heat

to build up and stay at a constant temperature. So it could be brick, it can

be many other kinds of stone. Actually, the key thing is that it be brick or

stone, and that it--you know, because even in gas-fired pizza ovens, they have

stone linings or stone on the bottom. And of course, when we reheat pizza or

make pizza at home, we use what is known as a pizza stone. And so what's

important is that it be stone or brick. Brick happens to be a particularly

effective heat transmitter and a holder of heat, but it doesn't necessarily

have to be brick. All kinds of stone can be used.

GROSS: So a gas oven with stone in it is good?

Mr. LEVINE: Yeah, is better than a gas oven without stone. The key to the

oven is how hot you can get that oven and whether you can maintain that heat.

In other words, the reason we can't make great pizza at home is because our

ovens only go up to 550 degrees. In a wood-burning pizza oven in Naples or in

this country or in a coal-fired brick oven, which is what all the seminal

pizzerias in America used in New York and New Haven and all these other

places--the coal-fired brick ovens and the wood-fired brick ovens get to a

thousand degrees. So the reason you can't make great pizza at home is because

we can't get the ovens hot enough.

GROSS: I've one last, very important question for you, which is, do you

always eat the crusts, the rim? Some people leave that over.

Mr. LEVINE: I know, but I think, if it's good, that great pizza crusts, like

at the pizzerias I love--I couldn't bear to leave the crust. The Neapolitans,

interestingly enough, because--they eat pizza with a knife and fork, because

they don't cut the pizza in Naples, so they often leave the outer rim, which

is called the cornicione, and they don't eat it. They just eat, you know, the

inner parts of the pizza. But I think that if it's a great pizza, that the

crust deserves to be eaten in full.

GROSS: Ed Levine, thanks a lot for talking with us.

Mr. LEVINE: Oh, thank you, Terry.

GROSS: Ed Levine is the author of the new book "Pizza: A Slice of Heaven."

Coming up, TV critic David Bianculli on the end of "NYPD Blue" and the new

season of "Deadwood," two shows created by David Milch.

This is FRESH AIR.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Analysis: Review of the final episode of "NYPD Blue" and the first

episode of "Deadwood's" second season

TERRY GROSS, host:

Last night, "NYPD Blue" ended its run after 12 years on ABC. This weekend,

the HBO Western series "Deadwood" begins its second season. TV critic David

Bianculli says the two shows have a lot more in common than pushing the

boundaries of sex, nudity, violence and language.

(Soundbite of "NYPD Blue")

Mr. DENNIS FRANZ: (As Andy Sipowicz) What do you got?

Unidentified Man #1: Looks to be like a high-priced call girl.

Unidentified Man #1: And the doorman called in the job. The manager's on his

way in.

Mr. FRANZ: (As Andy Sipowicz) What are you doing out of uniform?

Unidentified Man #1: Talked to building management, find out who's paying the

rent.

Unidentified Man #2: They're not in yet. You know, I thought once we cleared

the shooting, you were going to go back to patrol.

Unidentified Woman: Tell him already.

Mr. FRANZ: (As Andy Sipowicz) Chief of detectives gave me to squad.

Unidentified Man #1: When?

Mr. FRANZ: (As Andy Sipowicz) Last night at Medavoy's racket.

Unidentified Man #2: And you didn't say anything then?

Mr. FRANZ: (As Andy Sipowicz) I wanted to make sure that Duffy didn't change

his mind, and I didn't want to take away from Medavoy's night.

Unidentified Woman: The message came through this morning that it was a done

deal.

Unidentified Man #2: So wait. You're actually squad commander?

Mr. FRANZ: (As Andy Sipowicz) Yeah.

Unidentified Man #1: Congratulations.

Mr. FRANZ: (As Andy Sipowicz) Thanks, Gruten(ph).

Unidentified Man #1: I'd sure like to work with you.

Mr. FRANZ: (As Andy Sipowicz) No, huh?

Unidentified Woman: I'm not sure any of us can.

Mr. FRANZ: (As Andy Sipowicz) Well, that'll work out good, then, 'cause I

was planning on bringing in my own people anyways.

DAVID BIANCULLI reporting:

That's Dennis Franz as Andy Sipowicz, the one actor and character who was in

every episode of "NYPD Blue," at the beginning of last night's finale. He's

just shown up at a crime scene and he's almost shyly informing his co-workers

that he's just been promoted to precinct commander. It's an amazing journey

that Andy Sipowicz covered since "NYPD Blue" premiered in 1993. When we met

him, he was a mess--a racist, a drunk and on a self-destructive streak that

came within an inch of killing him, and that was all in the pilot episode.

"NYPD Blue" was co-created by Steven Bochco and David Milch. Bochco also was

one of the primary forces behind an earlier landmark police drama, "Hill

Street Blues," which also had at its center a recovering alcoholic with a

badge. But that character, Daniel J. Travanti's Frank Furillo, was in charge

from the start and ran his precinct as crisply as he dressed. Whatever his

demons were, he had conquered them long ago. He wasn't tempted by drink, he

carried on an affair with a defense attorney played by Veronica Hamel, and he

was one of the first leading characters on a prime-time cop show who actually

took time out to pray, to visit church, even to seek confession.

Sipowicz on "NYPD Blue" was a very different animal. For him, sobriety,

tolerance and personal growth came slowly, but come they did, and viewers

loved him for both his vulnerability and his persistence. Last night's finale

had him taking command and walking that tricky tightrope of having a bit more

power and responsibility than your friends and peers, but still having to deal

with and sometimes fight with the powers above you. Andy Sipowicz ended where

Frank Furillo began, with the respect of those under him but not those above

him. It's a nice, full-circle story arc, and it's also a familiar one.

On "Deadwood," the HBO Western series beginning its second season this Sunday,

central character Seth Bullock, played by Timothy Olyphant, is pretty much in

the same place. Cop shows often are deconstructed as modern Westerns, and

"Deadwood" makes it easy to track the comparisons. There's as much

lawlessness in isolated "Deadwood" as in Lower Manhattan, and town Sheriff

Seth Bullock, like squad commander Andy Sipowicz, accepted his position of

authority recently and reluctantly. And where Andy fought with the powers

that be last night on a political level, Sunday's season opener of "Deadwood"

has Seth prepared to fight his powers that be on a more literal level. In

this case, it's the town's most powerful figure, Ian McShane's imposing,

tough-talking Al Swearengen. Swearengen has insulted the sheriff by publicly

ridiculing his private affair with the wealthy town widow, insults Swearengen

continues to hurl privately once Seth shows up at Swearengen's room to pick a

fight. Swearengen is talking about outside interests trying to influence and

take over the "Deadwood" mining town, but Seth is more interested in removing

his gun and badge and throwing some punches.

(Soundbite of "Deadwood")

Mr. TIMOTHY OLYPHANT: (As Seth Bullock) How do you have this information?

Mr. IAN McSHANE: (As Al Swearengen) From the governor himself and a pricey

little personal note. They want to make us a trough for Yankton snouts and

them hoopleheads out there, thinking they booked us against going over to

those (censored). Now I can handle my areas, but there's dimensions and

(censored) angles that I'm not expert at. You would be if you'd sheath your

(censored) long enough...

Mr. OLYPHANT: (As Seth Bullock) Shut up.

Mr. McSHANE: (As Al Swearengen) ...and resume being the upright pain in the

(censored) that graced us all last summer.

Mr. OLYPHANT: (As Seth Bullock) Shut up, you son of a bitch.

Mr. McSHANE: (As Al Swearengen) Jesus Christ. Bullock, the world abounds in

(censored) of every kind, including hers. Of course, if it would steer you

from something stupid, I could always profess another position.

Mr. OLYPHANT: (As Seth Bullock) Will I find you've got a knife?

Mr. McSHANE: (As Al Swearengen) I won't need no (censored) knife.

(Soundbite of struggle)

BIANCULLI: The major link between "Deadwood" and "NYPD Blue," of course, is

David Milch, who co-created "Blue" and is the sole creator of "Deadwood." In

1993, long before cable's "Oz" and "The Sopranos," ABC's "NYPD Blue" was as

bold as TV got. Today "Deadwood," with its adult themes, brazenly coarse

language and complicated characters and plots, can make the same claim. Milch

left "NYPD Blue" a few seasons before it ended, but it's impossible to imagine

"Deadwood" without him. And you thought Andy Sipowicz had his demons? Check

out Seth, who has so much darkness battling with his essential decency that

he's almost as much villain as hero. In the same way, despite so many

despicable traits and acts, Al Swearengen is almost a noble villain.

"Deadwood" is no white-hat/black-hat Western. Everything and everyone is

painted with shades of gray.

In Sunday's season premiere, there's a moment when all the simmering emotions,

especially the lust and the anger, come to a head. When the violence erupts,

it happens suddenly and shockingly, and it matters. As on "NYPD Blue," change

occurs slowly, and actions have ramifications. It's a stunningly written and

stunningly performed series, easily one of the best on all of television.

GROSS: David Bianculli is TV critic for the New York Daily News.

(Credits)

GROSS: I'm Terry Gross.

We'll close with music by the British invasion band The Searchers. The band's

drummer, Chris Curtis, died Monday at the age of 63. This record was a big

hit in the US in 1964.

(Soundbite of music)

Unidentified Man: (Singing) I saw her today. I saw her face. It was the

face I loved. And I knew I had to run away and get down on my knees and pray

that they'd go away, but still they began, needles and pins. Because of all

my pride, the tears I gotta hide. Hey, I thought I was smart. I wanted her.

She didn't think I'd do, but now I see she's worse to him than me. Let her go

ahead, take his love instead. And one day she will see just how to say please

and get down on her knees. Yeah, that's how it begins.

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.