"From the Earth to the Moon."

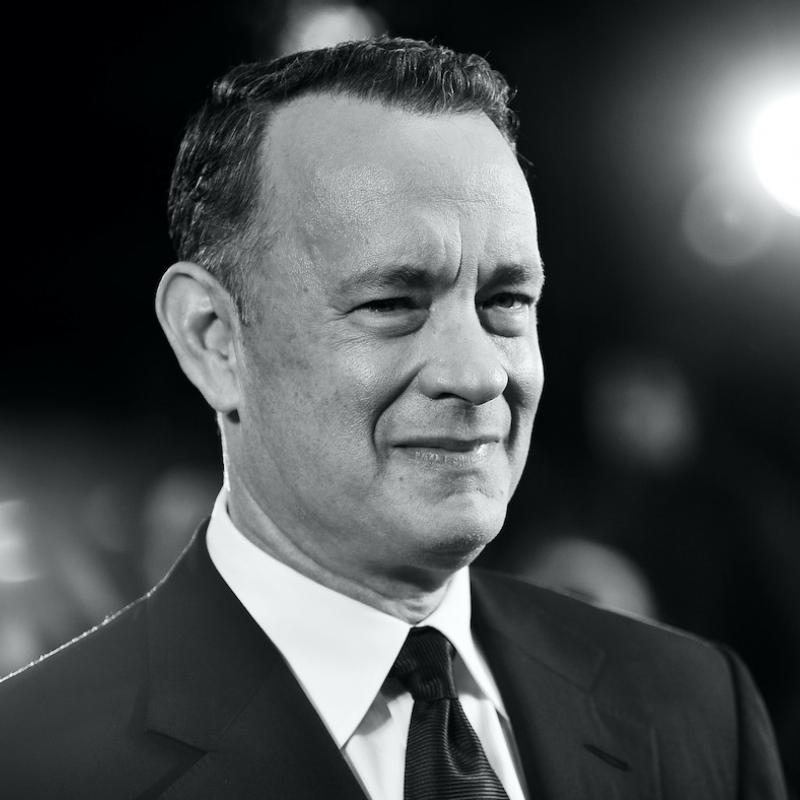

Actor, director and producer Tom Hanks and writer Andrew Chaikin talk with Terry Gross about HBO's 12 part mini-series "From Earth to the Moon" which begins this Sunday. Hanks was the executive producer for the project. Chaikin, a consultant on the series, wrote the book "A Man on the Moon" which program is largely based on. Hanks also starred in the film "Apollo 13". Hanks received Academy Awards for his roles in "Forrest Gump," and "Philadelphia."

Guests

Host

Related Topics

Other segments from the episode on April 2, 1998

Transcript

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: APRIL 02, 1998

Time: 12:00

Tran: 040201np.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: From the Earth to the Moon

Sect: News; Domestic

Time: 12:06

TERRY GROSS, HOST: This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

My guest Tom Hanks played astronaut Jim Lovell in the movie "Apollo 13." Now, Hanks is back in outer space. He's the executive producer of a 12-part docu-drama mini-series exploring America's Apollo space program. It's called "From the Earth to the Moon" and it begins Sunday on HBO.

The series starts with President Kennedy's 1961 challenge to send a man to the moon, and ends in 1972 with the last moon walk. Hanks directed the first episode and wrote the final one, but he doesn't appear as an actor. The mini-series is based in part on the book "A Man on the Moon: The Voyages of the Apollo Astronauts." The author, Andrew Chaikin, who was a consultant on the series, is also with us.

I asked Tom Hanks why he wanted to take on another project about the space program, after starring in Apollo 13.

TOM HANKS, ACTOR, DIRECTOR, AND PRODUCER: Because there were so many stories that were both anecdotal and inspirational that would never see the light of day in any other medium. And actually meeting a lot of the men who both worked in Houston and, by the way, who also flew and walked on the moon -- I just kind of stumbled upon, naturally, this treasure trove of amazing -- amazing yarns, literally -- just gripping stories -- that Apollo 13 rightfully captured as far as its mission went. But there were moments fraught with great drama, anxiety and personal vision in Apollos 12 through 17, and Apollos 1 through 10.

And I -- I was just anxious in order to bring what I thought really was just a very cool story to the air in some medium that would provide the time.

GROSS: Andrew Chaikin, why did you write A Man on the Moon, which is a history of the Apollo missions? What's your fascination with space?

ANDREW CHAIKIN, AUTHOR, "A MAN ON THE MOON": Well, you know, I was one of these kids that was absolutely captivated by Apollo when it was happening. I mean, I -- you know, I grew up totally in love with the sky. I mean, I was one -- I knew where the planets were when I was five years old. And I think it was probably Ed White's walk in space, you know, during the Gemini program that just totally hooked me on the astronauts.

And every mission that would come on, I would be glued to the TV with, you know, models of the space craft and maps of the moon and, you know, my parents had friends who worked in the TV industry so we had -- I had press kits that they had gotten me. And I was following the missions as if I were, you know, somehow by magic that a 12-year-old kid could be part of NASA. You know, I did everything that I could possibly do to kind of create that illusion for myself.

And you know, I was lucky enough to meet some of the astronauts. My parents took me to Cape Kennedy for my 13th birthday, and just by luck, stayed at the motel where all the astronauts were staying.

So, I lived it. It was the most exciting thing that I could possibly imagine happening, and it was happening before my eyes. I mean, something that had been science fiction and that I had watched movies about was now coming true.

GROSS: Tom Hanks, you had a $65 million budget for this 12-part series.

HANKS: Not to begin with. To begin with, we had a $45 million budget. God bless HBO.

GROSS: Well -- it seems actually quite scary to me to have, like, a 12-part series on space travel, to have to do with this, you know, really large budget for television, certainly. I mean, that's -- did you really want to take on that much?

HANKS: There was no other way to do it. In -- before we even went forward with approaching HBO, we knew that this was going to be very expensive. And it wasn't the first thing that came out of my mouth in the very first meeting we had with Chris Albrecht (ph) and the executives there, but it was probably the second.

I said: "look, this is going to be -- it's going to take at least 12 hours" -- actually, back then it was 13 hours 'cause we were going to attempt a Soviet space program as well, which fell through the cracks. We just couldn't do it. But those 12 hours of this is going to be very costly because it can't be anything but.

We were cognizant of the fact that whether we are -- whether we do this well or whether we do this poorly, we will probably be the definitive, dramatized version of this facet of our history. We will be the record of Apollo, whether we do a good job or bad job. And just by dint of that, we knew that special effects as well as locations and actors and the amount of people that we'd have to hire in order to do this was going to be very, very costly.

GROSS: Tom Hanks, you directed the first episode, which is about the very beginning of the space program...

HANKS: Yes.

GROSS: ... John Kennedy's challenge to have a man on the moon by the end of the '60s. And that episode ends with the Gemini 8 mission that had to abort. Why did you decide to direct that particular episode?

HANKS: Well, I knew that it was going to be problematic and that we were going to have to bust a bunch of rules as far as being a "pilot" episode for what a series is. There were -- there was an ocean of faces that we had to establish, and yet not linger on very long in order to get everybody (unintelligible). And there was a huge volume of information that we just needed to lay down.

In show business parlance, it's called "shoe leather" or "pipe" (ph) -- you have to like essentially set the stage for what it our real story. There's not a single Apollo launch in the first episode. It's all one Mercury mission and four Gemini missions that are by and large forgotten.

And I felt as though that with as long -- a script that constantly stayed in flux right up until we were -- actually until just last December where we shot some extra scenes for it in order to flesh it out -- I knew that there was going to be this odd and undefined sort of logic that would have to be established by this first episode. And I honestly didn't know what it was. I couldn't give that over to a screenwriter or a director and say: "listen, I know what this thing is -- but go off and shoot it. We'll make sense of it later on."

I am a member of the DGA so I could say: well, you know what? I'm going to volunteer for what is not the -- it's kind of grunt work here, but I'll do some heavy lifting here and hopefully at the end of it, we'll have -- honestly, it's not even overture; it's more like a prelude to the rest of the series, trusting that no one really would be able to figure that out except me and a few other trusted advisers on the show.

GROSS: Now if I'm not mistaken, one of the things that you have in that first episode is the first walk in space.

HANKS: Yes, yes. Ed White's walk in space.

GROSS: So, how did you stage that?

HANKS: Well...

GROSS: This is a scene where the -- you know, an astronaut's in space attached by like an umbilical cord to the spacecraft.

HANKS: Yes. There were five things that needed to be proven before anybody could go to the moon. And one of them was that it was going to be possible for a human being to get outside of a spacecraft in the vacuum of outer space; that a suit could be developed and that he would be able to live and breathe and survive however long it took, because obviously you can't walk on the moon without getting outside of a spacecraft.

So this was something that had never been done before, except by Alexei Leonov (ph) a few months prior to Ed White. And this was always one of the big things about the first episode. We were going to make -- we were going to show this in such a way, to an audience, by the way, that has become, you know, honestly -- they've seen this 100 million times in any number of science fiction films or television series'. That is, if we're going to try to bring it back in a oddly operatic, poetic, balletic sort of fashion so they'd understand it.

Well now wait, that's a cool thing to understand -- the idea of opening a hatch as you're flying fives miles a second, you know, 200 miles above the planet Earth, and then getting out and drifting around on a gold umbilical cord, would probably be a very beautiful thing.

As it turns out, it was very uncomfortable. It was very physically demanding of Ed White. It was not an easy thing to do. But you know what? We just sat down and said: OK, how are we going to do this? And we stuck some -- we have a very -- it's a sequence that has almost every one of the current modes of special effects photography in it.

We do do models. There is some computer-generated animation. There is a stuntman that's hanging from a tether. There is a stuntman standing on the floor as the camera does some interesting things.

And we just -- we just sort of like figured it out -- a way to get from that hatch opening up to the final moments when he gets back inside.

GROSS: You know, it's funny. I think our ideas of space have been formed at least as much by movies like "2001" and TV series like "Star Trek" as by the actual flights. And Tom Hanks, I read that you saw 2001 22 times in a theater?

HANKS: Well, it's now up -- it's now over 30.

GROSS: It's up.

HANKS: It's over 30 now. As a matter of fact...

GROSS: This was long before you started making space movies.

HANKS: ... I've seen it projected -- that's the big deal. I have it on laser disc and I've watched sequences of it, but yeah I've seen it projected -- as a matter of fact, it was just re-released about two years ago and it played in the Cinerama dome here in Los Angeles and I was one of about 42 people at 2:00 in the afternoon sitting in and watching again.

And lo and behold, I see something new every time I see the film. So ...

GROSS: What did you see in it initially that got you back 22 times before you started seeing...

HANKS: Oh, I can tell you quite -- I can tell you quite easily. It was the two sequences of the -- of the flight of the PanAm space shuttle to the Blue Danube; and then the flight of the Aries One-B Mooncraft (ph), also to the Blue Danube that is carrying Dr. Heywood Floyd to the moon.

The thing you have to remember -- what I consider about 2001 is that this was not a fantastic, impossible future that we were seeing, rendered by Stanley Kubrick. This was literally what was going to happen. All of the -- all of the spacecraft, all of the procedures that we saw these characters doing -- riding around in -- upside down in a circular space station, strapped down in a space shuttle -- this was -- this was the physical reality of the direction that the hardware was going.

We weren't seeing like rocket ships that were shaped like, you know, discs. We weren't seeing "Lost in Space" with the "Space Family Robinson." We were seeing where the next generation of the Apollo spacecraft and the shuttle was.

So this -- we were literally having a window into the future of what it was going to be like within our lifetimes or (unintelligible). I'm going to be 44 in the year 2000, and that means by that time, we'll be able to watch that space station go over our house, you know. And it's going to look just like that, because that's what it's based on in physics.

And I -- this is -- this is the reason that I went back again and again and again and again, because I was seeing -- I was -- in real life, I was looking at the first draft of "2001: A Space Odyssey" in the form of Apollos 8 and Apollo 11 and Apollo 12. And this was just going to be a few years in the future.

GROSS: Tom Hanks, your HBO series From the Earth to the Moon not only chronicles the success of the Apollo missions, it chronicles, you know, the failures. And I'm wondering what some of the failures were with making the TV series -- in other words, some of the special effects that went bad; some of the little disasters on the set as you were making the movie.

HANKS: Oh, well we had a -- the reality is we were shooting our lunar surface sequences in a huge zeppelin hangar in Tustin, California -- 38,000 square feet of lunar soil, all sorts of different -- oh, I mean, it was just the biggest place you've ever seen. And we found that when we put the stuntmen -- it was usually stuntmen that were in the -- were actually in the suits. We had actors come down for very specific scenes, so that they would be incorporated into it.

But the stuntmen could honestly -- they could only take about two and a half hours inside these suits. We had them attached to huge helium balloons. This is a big thing that we went through on the series. I didn't want our lunar surface sequences shot in slow motion.

If you look at the video, which I have extensively, of the actual missions, everything happens in real time. They move their hands in real time. And the only thing that is oddly different is that they have this kind of gait that is allowed them by the one-sixth gravity. But other than that, it doesn't -- it just looks odd. It doesn't look in slow motion.

So we had -- we had various stuntmen attached to huge helium balloons that would -- helium balloons -- I mean, the zeppelin hangar is -- I don't know? How is it -- it's like six storeys tall on the inside. It's a big massive deal. It's as big as a zeppelin I guess.

CHAIKIN: It's enormous.

HANKS: Actually, it was a little bigger than a zeppelin, otherwise you couldn't get a zeppelin in it.

CHAIKIN: Yeah.

HANKS: And so we had these black helium balloons that were 50 feet in the air, and huge ropes or cords that were attached to special harnesses on them. And they were in these very heavy and bulky and hot re-creations of the actual lunar -- lunar EVA suits. And the poor guys -- I mean, it just beat them to death. They just couldn't take it for more than two and a half hours. And it was very slow moving the equipment. It's very slow setting up the shots.

So what we were hoping to get in 15 days of lunar surface photography turned out to be 30 days, because literally the human beings couldn't take the punishment.

GROSS: What did you learn from Apollo 13 about how to and how not to shoot space scenes?

HANKS: Well actually, inside the command and lunar modules, it's really not that difficult because honestly, we were on teeter-totters or just standing on apple boxes and you can tilt the camera to make it look anything -- you know, you can do a lot inside these very controlled atmospheres.

The real -- the real mold that we broke on Apollo 13, I think, was truly trusting the audience to understand what we're talking about. There is a philosophy that says look, the audience doesn't know what -- anything about orbital mechanics, so we can't hang any dialogue talking about orbital mechanics. Yes we can, because it's going to be like, you know, they see a movie in French and it's subtitled. After a while, they forget that they're reading the subtitles and they're just hearing the French, but they're understanding it.

You know, the idea of "OK, rocket ship go, retro rockets fire" -- you know, we had a lot of, you know, OK, we got the IDC lines; we're going to have, you know, we had the whole lessons about what gimble (ph) lock is. The audience didn't need to understand gimble lock. They just had to know that gimble lock was a bad thing.

And we were able to communicate that after a number of forays into the transcripts.

GROSS: My guests are Tom Hanks, the executive producer of the new HBO mini-series From the Earth to the Moon, and Andrew Chaikin, the author of A Man on the Moon, which the series is partly based on. The series begins Sunday.

This is FRESH AIR.

My guests are Tom Hanks, executive producer of the new HBO mini-series From the Earth to the Moon, about the Apollo space program; and Andrew Chaikin, the author of A Man on the Moon, which the series is partly based on.

You know, I've often wondered how astronauts have been changed by the experience of being in space. And Andrew Chaikin, your book ends with -- well, toward the end -- there is a description of that. It's a question, I think, you asked a lot of the astronauts, and some of the answers were pretty interesting, like Pete Conrad told you that he always used to say to people when they asked "how did it change you," "how was being on the moon" -- he'd say: "super. I really enjoyed it."

CHAIKIN: Well ...

GROSS: And Stu Roosa (ph) said: "space changes nobody." He was in Apollo 14.

CHAIKIN: Yeah, I -- I mean, this was one of the most intriguing questions to me when I started writing the book because I always felt that if I got to go, you know, it would blow every fuse in my head. It would just come back with a, you know, a completely new set of wiring. And I found to my disappointment sometimes before I really got to understand these guys, that quite a few of them took the experience in their stride.

I think the misconception that a lot of people have is that the astronauts were emotionless; that somehow they were robots or they were just, you know, right stuff fighter jocks who just were, you know, doing the job and just, you know, brushed it off.

That's not the case. Even a guy like Pete Conrad who -- who you quoted there -- now Pete's an interesting guy. The day he got selected to be an astronaut, he said to himself: "if I get to go to the moon, it's not going to change me."

Now, I can't think of too many people who would decide that seven years in advance. And then, he got to go. And I think for him, and for a lot of the guys, it was a professional thrill. It was a thrill to be on the moon. It was the ultimate test flight. But then they came back and he's still Pete Conrad and it's not -- he doesn't go out and look at the moon and feel awe. He doesn't do any of that stuff.

Then you've got guys like Jim Irwin (ph), who flew on one of the later missions, came back from the moon and said he had felt the presence of God there, and you know, only lived -- he lived for another 20 years after he came back from the moon, and every one of those years he spent going around the country as a Christian minister. He convert -- he became an ordained minister and shared his faith by way of his moon tales, you know.

The thing that I loved about interviewing these guys was that there was a whole range of responses, and some of them were sort of in the middle, you know. Bill Anders (ph) on the flight of Apollo 8 -- the first man to see the Earth rise. He took that famous photo that we've all seen of the Earth coming up beyond the moon. And said to me that he could see with his own eyes that Copernicus was right; that the Earth was not the center of the universe.

And that is a very powerful realization. But he didn't go off and become, you know, he -- they kind of slough it off. He says: "oh, I didn't go off and become an environmentalist," you know. In fact, he went off and became head of General Dynamics.

So, the range of responses is almost as great as probably any other group of people. It's just that we're starting with a group that comes through some very narrow filters. So, there's some interesting things mixed in.

GROSS: Tom Hanks, did you get to talk to a lot of astronauts about their experiences and how it changed them?

HANKS: Yes I did. In the course -- well, starting with Jim Lovell and eventually getting around to as many as I could honestly collect. And what I have found is that they just came back more of who they were when they left, you know.

Al Bean on Apollo 12 was -- really -- probably he dallied in art at the time, you know, a little bit of painting. And now he has dedicated himself to -- he wants to paint 200 paintings, and much like Monet painted "The Water Lilies," he's painting the lunar surface, and they're actually quite extraordinary paintings.

My -- my favorite, in a lot of ways, is Gene Siernan (ph), who was the commander of the last lunar mission, Apollo 17. Gene is a man who can talk for a long time about what it was like to be in space.

CHAIKIN: That's true.

HANKS: He is a guy -- and you know what? -- he loves it. You know, you can ask him a question: "hey, Gene, what was it like to walk on the moon?" He can fill -- he could fill two and a half hours with that -- without even breaking stride. He had a great -- a great anecdote that he shared with me when I was talking to him, 'cause I wrote the last -- the last of the episodes. And he said: "Tom" -- he says that a lot, you know -- Terry, he said: "Tom...

LAUGHTER

... "and I'm just -- I just can't wait to hear what he says -- he said: "I -- I looked up" and he says "I was there -- I was there monkeying about with a fender" -- you now, he had to fix a fender 'cause he broke a fender on the lunar rover and he was taping it up -- "and I looked up at the Earth just right over there over the South Massif (ph)" -- you know, over this big (unintelligible) jagged peak that's up there on the moon -- and he said: "I could see that the sun was going down in England and it was lunchtime in Houston."

I said, well, shoot Gene, you were like standing on a time machine. You were literally looking at what time and space could do.

"That's right, Tom, I was having adventure right there in time, space, and reality."

Now, you can -- you can wash this off as, you know, a degree of bluster from a guy who's very good at public speaking, and also very proud of what he's achieved. But it doesn't take a lot of imagination to put ourself in the same thing; that look, we've all become used to looking at photographs of the ball -- of Earth and it's this blue and it's green and it's brown and it's white and it's lovely and -- but we understand that's everything that we are and who we are and what we know.

But also that you're looking at it from a point of view where you can see that people are going to bed in London and they're just sitting down to lunch in Houston, with a casual glance of your eye. And that puts it in a perspective for me that makes all of these guys extremely unique.

GROSS: Tom Hanks is the executive director of the new HBO mini-series From the Earth to the Moon. Andrew Chaikin is a series consultant and author of A Man on the Moon.

Tom Hanks will be back with us to talk about his movies in the second half of the show.

I'm Terry Gross and this is FRESH AIR.

This is FRESH AIR. I'm Terry Gross.

Back with Tom Hanks. He's the executive producer of the new HBO mini-series From the Earth to the Moon, which dramatizes the history of the Apollo space program.

We're going to talk about several of Hanks' movies, including Apollo 13, which led him to make the new mini-series.

What impact did it have on you to play Jim Lovell in Apollo 13? And did you get to meet him and find out what impact it had on him for you to have told his story?

HANKS: Well you know, it was actually -- I was very afraid of my countenance being used in order to be -- portraying an astronaut because I was -- oddly enough, I had swallowed the myth hook, line and sinker of you know, these -- you know, the iron-jawed, steely eyed, you know, throttle-jockey aspect that has really been spoon-fed to us as though we get our sense of history from Wheaties boxes.

And by meeting Jim and realizing that on first glance, you would assume that Jim is a successful dentist or a well-read insurance agent. He's not a tall man. You know, he's not a muscular man. He's not a scary man. He's not an intimidating man. He is just this really great guy who you find out has made 100 night landings on an aircraft carrier in the Sea of Japan. And oh -- by -- also by the way, was one of the first three men to leave the Earth's gravitational pull, orbit the moon, and come back. And was also the commander of Apollo 13.

To realize that these guys who are -- were literally interplanetary explorers or the closest thing we had to interplanetary explorers are not all that different from you or I; that indeed, somebody who has my countenance and my outlook and the same attitude when he gets out of bed could indeed be someone who leaves the planet Earth.

That was something of a -- an eye-opening catharsis for me, and made me feel -- made me feel as though, you know what? -- I'm the perfect guy to play Jim Lovell. At first, I thought I was as far removed, but after meeting him and getting to know him and hanging around him I realized that if you're going to cast somebody to play Jim Lovell, you better come and get me.

GROSS: What did you learn as an actor about what it's like to be in the space suit and to be in the capsule and so on? Or to perform in the role of an astronaut who's not particularly demonstrative emotionally -- you know, demonstratively emotional person, that you were able to pass on to the actors you worked with?

HANKS: Well you know, the -- the -- it was really the concept of look, you guys, I was always saying: look, you guys know this stuff back and forth. You know this. You know what it is that you're talking about when you're flicking these switches. So don't arbitrarily flick switches. Don't simply go click, click, click, click, zib, zib, zib, zib, zib -- because you know what? You don't do that. You've been sitting there. You've covered this. You've rehearsed this 100 million times in drills and tests and full-up simulations. You've been in the simulator for thousands upon thousands of hours recreating this stuff.

So, don't do anything arbitrarily. Actors, though, you know this stuff backwards and forwards because they did. These guys, you know, you can still ask them about moments on the flight plan and they can rattle off, you know, nine different things that they had to do.

"Well let me tell you, Tom, you know the problem with the glycol (ph) pump is often that you have ..." -- you know, suddenly I'm lost and get in this guy's reverie of what it means to stir their cryo (ph) tanks.

But that was the -- the idea that they were incredibly accomplished human beings -- it was as though, like look, imagine you're playing a concert violinist. If you're playing a concert violinist, you're not going to be intrigued by these things that intrigue you about being a concert violinist, 'cause you've done it 100 million times.

So just sit there and play the violin like you -- you've known this piece of music for 100 million years.

GROSS: You directed the first episode in this new From the Earth to the Moon series. What's the best direction you've ever had in a movie that you weren't directing, but you were acting in.

HANKS: Oh, "do it different." That was it. It was literally: "just do that different." You get to the point where you're an actor and you think that what your job is to sit at home the night before and say: "OK, here's how I'm gonna do this. Here's how I'm going to say this line. And when this moment comes, I'm gonna turn. I'm gonna give this look. And with that look, it's going to communicate everything that I want communicated in the scene. And that's what I'm gonna do."

And you think that that's what your job is. Well you know, your job is to get there and tell the truth, according to the dictates of the scene. Spencer Tracy said this. He said: "the actor's job is to hit the marks and tell the truth."

You have to be in the reality of that very specific moment, and there are times -- I mean, this was very early. You know what? I'll tell you. It was in a TV movie I did called "Rona Jaffe's Mazes and Monsters" and the director said to me: "you know, that was great. That was fine. That was OK. Do it different."

And I felt: "do it different? My God, man. I've done all this preparation for this. This is -- this is what -- this -- you don't understand. I'm an artist." And -- but in a moment, a light went off in my head -- a great illumination I might add -- that said: "oh I see what he's saying. I see what he's saying."

GROSS: And what was he saying? Yeah, go ahead.

HANKS: He's saying that was fake...

GROSS: Right.

HANKS: ... and that was baloney and that's what you want us to believe is going on. But you know what? We can see that you've just made these arbitrary choices in order to make it seem as though you're undergoing something and the fact is I'm not believing it. So, please do something different.

And that is -- that demands a lot of things. That demands a certain fluidity and a certain -- as well as a trusting of the text itself as opposed to your sole interpretation of what that text is.

GROSS: So, when you as a director have to tell an actor to do it different, is that -- are those the words that you'd use? Or is there a nice or not-nice way of putting that?

LAUGHTER

HANKS: There's other ways of doing it. Hopefully, you've had enough communication with your actors prior to that, so you sort of speak the same language. And I must say, you know, I'm perfectly willing to take that kind of blatant direction from guys, but it's -- there's ways of doing it. See, you can -- 'cause you can come and say "you know what this" -- Nora Ephron does this a lot. I'm making a movie with her right now. Nora always comes up and...

GROSS: And she wrote "Sleepless in Seattle."

HANKS: She wrote Sleepless in Seattle and directed it. And she says: "you know what this moment is? This is the moment where you know that you're doing the right thing, but in fact you're not doing the right thing."

LAUGHTER

And you -- you say -- well, there's an infinite possibilities of what she means there, and I think I do understand what she means. And so you end up going off down this road. And that is essentially a very cool way and very polite way of saying: "do something different."

Because how knows -- when they put this movie together six months from now, that one thing that you are providing and recreating over and over again may not be the thing that's going to make the scene. So you have to trust the fact that there is a -- there is a degree of serendipity that goes into your performance on any given day that can make or break that scene, and therefore the whole enterprise.

GROSS: When you started acting, did you ever practice in front of a mirror so you could actually watch what you were doing and see what the effect was?

HANKS: No, no. There was a time I worked with videotape cameras, but I found that that was a -- such a narcissistic way of doing it and I was just falling into even greater traps. The -- as an actor, I must say, I'd be damned if I could tell you what my process is 'cause I don't ever want to think about it because then I'd probably start paying too much attention to a process that I have written down as opposed to some instinctual push towards preparing for the role.

But the thing that I do more than anything else is that I just read the text over and over and over again. Because every time you read it, you see something new and every time you read it, you find out something that you missed the first time, and you realize there's something that somebody else is saying is much more important to the thing than what you are saying.

And so that you -- by the time you -- hopefully, by the time I show up on the set, I'm so familiar with the text that I can go any way the director would like me to go, and I'll feel confident in getting there.

GROSS: My guest is Tom Hanks. He's the executive producer of the new HBO mini-series From the Earth to the Moon, which begins Sunday. We'll talk more about his movies after a break.

This is FRESH AIR.

Back with Tom Hanks.

You wrote, directed, and co-starred in the film "That Thing You Do" a couple of years ago, which was set in the same era as your space series. It was set in 1964.

HANKS: Those go-go '60s.

LAUGHTER

GROSS: About a small-town rock band that becomes a one-hit wonder. And I guess -- I'm wondering if those two themes are connected in your mind? You know, this one-hit wonder rock band of the '60s and the moon flights.

HANKS: Well, I have to tell you that I'm 41 years old and like -- I have that -- I have a degree of the disease that everybody else my age has.

GROSS: That my era was the most important era?

HANKS: Well, you know what? Yes, exactly right. The people who are 10 years older than us think differently and the people who are 10 years younger than us think differently as well. I must say, I look back on those -- and actually -- what? -- we were just talking about when I was nine years old.

I can probably remember moments when I was nine years old better than I can remember moments from when I was 39 years old, because they were so indelible. And all I can remember is the Beatles were so cool, and there was nothing more magical than the Ed Sullivan Show when the Beatles were going to be on it.

And I remember distinctly walking across that playground in Mrs. Castle's (ph) class to sit in the auditorium to watch a Gemini capsule sit on top of an Atlas booster and go nowhere for hours on end. And it was -- these were -- these -- I'm not a great filmmaker. I'm not a great storyteller. I'm some guy who works in the movies.

But you know what? When it comes down to the stuff that I really do have a passion for and I think I can recreate on paper, it always -- it's going to come out of my own experience somehow, especially right now. And these things -- these things that are so powerful for me are truly -- I can tell you -- the three big -- the big three from my life are the Beatles, and it is the Apollo space program, and it is Vietnam.

I still ponder all three of those things over and over again. I read them...

GROSS: Well, OK.

HANKS: ... I read them as hobbies.

GROSS: It's interesting that you mention Vietnam because I think for a lot of people during the Vietnam War, the space program had a sense almost of irrelevance or of misplaced values, you know. We're fighting this war; we're killing people in another country; there's poverty in our own neighborhoods. And yet, we're sending men to the moon.

I mean, some people were really quite outraged about that. How did you reconcile that?

HANKS: Well, we just -- we just pay homage to the fact that they were going on hand-in-hand.

GROSS: Right.

HANKS: We -- our -- our fourth episode, which is entitled 1968, which is about our -- the Apollo 8 mission, really chronicles month by month everything that went on in that year, starting in January and ending in December.

The -- the -- almost -- the cruel twist of fate in regards to the Apollo moon program is that it did happen as a bookend to Vietnam -- in tandem. And here was this thing that was siphoning off so much of our attention and so much of our grief and so much of our money, to a tragic and -- What's the other? What's the word? -- oppressive end, really. I mean, there was no escaping Vietnam at the time.

And on the other side of it, here was this altruistic thing that was expanding the horizons of humankind that was also costing an awful lot of money.

GROSS: Were you of draft age during the war?

HANKS: No, no I was not.

GROSS: You know what I find interesting in a way, you know, at the same time that we have the Apollo missions, it's a period that your movie That Thing You Do is set, and it's such a lo-fi period. I mean, people are still selling like hifis in appliance stores along with refrigerators, and you know, we have like, you know, wax records that break and scratch and, you know...

HANKS: They have this needle that goes around in a groove.

GROSS: Yeah, exactly.

HANKS: I mean, you know, it literally rubs in a groove and that's how you hear the music.

GROSS: I mean, the space -- the space accomplishments of the '60s seem -- still seem just absolutely spellbinding and fantastic, whereas the audio quality of the '60s doesn't seem very good.

LAUGHTER

HANKS: Well, there's something to be said for that -- good quality mono recording. There's something about that -- well, that fine Phil Specter wall of sound that has a unique (unintelligible).

GROSS: You know, years ago, if somebody would have been making that -- the rock movie of yours set in the '60s, you would have been one of the young rock musicians. But of course, you, as an older -- comparatively older actor -- played the agent. At what point did you realize that you weren't going..

AUDIO GAP, WILL SEND TRANS

... in movies?

HANKS: I could tell you, it was just prior to doing a movie with Penny Marshall called "League of Their Own." I found -- you know, I -- I had...

GROSS: That was a women's league baseball movie.

HANKS: Yes, yes. I had -- I had had a career and was actually relatively lucrative, of playing guys who seemed to be suffering from the Peter Pan syndrome for most of their lives. You know, guys who, you know, can't -- looking for, you know, the good relationship with a woman and there was an awful lot of that.

And I just reached a saturation point where I sat down with my crack team of show business experts -- both of them -- and said: "you know what? I think I'm done doing that. I want to play men who have histories; men who are dealing with other aspects of their humanity, rather than 'jeepers-creepers, I don't have a girlfriend.'"

Or to that effect. I mean, I -- I made a movie called "Big" in 1988, which was probably like the epitome of the boyishness that I bring to a role. And after that, I -- honestly, I just felt -- I felt done. I felt as though I can't go back and examine this stuff anymore. I'm not against being charming in a movie. I'll try to -- I'll try to dredge that up, but as far as being boyish, I just can't do it anymore.

GROSS: Where did you find the right body language and voice for "Forrest Gump?" Where did you look in yourself for that?

HANKS: Well, it -- the first thing that I understood about Forrest when it began was that he couldn't operate faster than his own common sense. That's the one thing that I got from reading it. That's the one thing I presented to Bob Zemeckis (ph) and Eric Roth (ph) who wrote it. I said: look, I don't know anything about this guy except he can't operate faster than his own common sense."

So that automatically made him "slow" or hesitant, and not very -- not very verbal. Everything else, I must say, came through this long period of -- of bad experimentation on my part of trying to find this guy. And it didn't honestly click in until the young actor who played the young Forrest and I met.

And we did some camera tests -- screen tests -- here in Los Angeles about maybe -- maybe a month or two months prior to beginning of shooting. I just said: "Lord, this kid is perfect." And we -- I had a brief conversation with him. I said: "look, don't have this kid change anything. Don't make him do anything that I have ideas. That's going to be virtually impossible. Let me -- let me just take him."

He was a fascinating kid. He was a good kid and he had this distinctive way of talking that I was following him around with a tape recorder, and then sat down with the dialogue coach, a woman by the name of Jessica Drake (ph), and I said: "OK, how do we make this an organic -- an organic thing that comes out of my mouth?" And what we did in the two weeks prior to beginning the shooting was we slowly read the entire screenplay out loud. I read it to her -- every page number, every exterior -- Forrest Gump's house; it is a sunny day on the river; and Forrest is mowing the lawn.

You know, and -- and I said everybody's -- I said everybody's dialogue; I said every fade in; I said every fade out; I said every "cut" too. And it took a real long time. But by the time we were done, it was -- it was locked in my head enough so that I could put on the clothes and go out and be Forrest.

GROSS: Right. I'm curious about the ideas that you rejected...

LAUGHTER

... for the role.

HANKS: Oh, they were pretty bad. You know, it's like bad Southern accents and this is -- I must say that this is a really -- you talk about how you -- how you prepare to do this, and you have to fail horribly before you can figure any of this stuff out.

You really have to be bad. And you have to trust that that badness is like being on a river and you're floating downstream even though you don't realize it, and you're going to get there, but you have to go up these tributaries that are really quite ugly and terrible and embarrassing.

And you could probably -- I could probably play you some audiotapes of early passes we made at the voiceover of Forrest Gump. And it's just God-awful. But we knew it was God-awful when we were doing it. I experienced it in some ways as well when I was doing a movie called "Punchline" and I had to get up and do standup comedy in clubs and I had no act.

But it's a terrible feeling to get up on stage and bomb, but I knew that I had to get up on stage and bomb before I could get up on stage and be any good. And that was the only way of getting into the -- getting the research done and getting material for the character.

And so you sort of have to like put all of your self-consciousness aside and say: "I'm really going to be terrible" -- for about six weeks. And hopefully at the end of six weeks, we'll actually be on the right track.

GROSS: Now, I have to ask you -- the movie "In and Out" seemed to be a kind of "what if" movie that took off from your Academy Award acceptance for the movie "Philadelphia" in which you thanked a teacher who was gay, as being the inspiration for your (unintelligible).

HANKS: The best reviews of my career -- the best reviews of my career in In and Out, and I'm not even in the movie. I was mentioned in the first paragraph of every single review.

GROSS: Right, right.

HANKS: And I didn't get a dime for it.

GROSS: So did -- you didn't really "out" your teacher, though, did you?

HANKS: No, I did not. No, that was a -- that was a -- I think one of the -- a tabloid said I did, and it was far from the truth.

GROSS: And -- what was his reaction to your...

HANKS: Well, this is my drama teacher in high school, Raleigh T. Farnsworth (ph), and I had -- I had called him about a week prior to the Academy Awards. And I hadn't seen -- I honestly -- I hadn't seen him. I hadn't spoken to him since, you know -- I actually kept in contact with him a little bit after I graduated from high school, but honestly, it's been 20 - 20-some odd years.

But I called him on the phone, tracked him down, and said: "Raleigh -- Raleigh -- Mr." -- I said: "Mr. Farnsworth? Tom Hanks here." And he said: "Well, hello how are you?" And I said: "well, I'm fine." And I explained, you know, he knew that I was nominated and he thought I might -- and he said: "well, I think you're gonna win."

And I said: "well, if I do, is it all right if I mention your name and if I mention that you're gay and that I'm able to say thank you for it -- because I think it's -- obviously it's part and parcel to the reason that I'm there." And he said: "well, I think it would be wonderful."

And so I did. So I did ask him if it would be all right, and he was a very proud man and I was very proud to do it.

GROSS: Tom Hanks. He's now the executive producer of the new HBO mini-series From the Earth to the Moon, which begins Sunday.

This is FRESH AIR.

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

Dateline: Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest: Tom Hanks; Andrew Chaikin

High: Actor, director and producer Tom Hanks and writer Andrew Chaikin talk with Terry Gross about HBO's 12-part mini-series "From Earth to the Moon" which begins this Sunday. Hanks was the executive producer for the project. Chaikin, a consultant on the series, wrote the book "A Man on the Moon" which the program is largely based on. Hanks also starred in the film "Apollo 13," and received Academy Awards for his roles in "Forrest Gump," and "Philadelphia."

Spec: Movie Industry; Cable; HBO; From the Earth to the Moon; Tom Hanks

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1998 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1998 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: From the Earth to the Moon

Show: FRESH AIR

Date: APRIL 02, 1998

Time: 12:00

Tran: 040202np.217

Type: FEATURE

Head: A Scientific Romance

Sect: News; Domestic

Time: 12:55

TERRY GROSS, HOST: Ronald Wright is the author of travel essays in the acclaimed 1993 book "Stolen Continents," which looks at the exploration of the Americas from the point of view of its native people. In Wright's new novel, "A Scientific Romance," he offers us a more unusual kind of travel tale.

Book critic Maureen Corrigan has a review.

MAUREEN CORRIGAN, FRESH AIR COMMENTATOR: H.G. Wells called his fantasy tales "Scientific Romances" -- meaning that he was more interested in the larger philosophical questions of "what if" than in the nuts and bolts sci-fi problems of "how." Because in novels like "The War of the Worlds" and "The Time Machine," Wells imagined his way into the technology of tomorrow, many people mistakenly think of him as a stereotypically sanguine Victorian.

Instead, he's the chief pall bearer at the funeral of 19th century optimism. Wells' Scientific Romances are suffused with weariness and melancholy -- none more so than his first novel, The Time Machine, published in 1895. It's so haunting and so short, I've always yearned for more every time I've read it.

Wells never wrote a sequel, and the many clever and often campy literary and movie spinoffs of The Time Machine never quite capture its elegiac mood.

But Ronald Wright's new novel, appropriately called A Scientific Romance, comes awfully close. Wright successfully carries forward the spirit of Wells' gloomy masterpiece in a distopian adventure tale that suits the turn of our own troubled century.

Like the original Time Machine, A Scientific Romance is composed of a boxes within boxes structure of letters and journals that contributes to the novel's aura of mystery. A simplified plot summary would go something like this: the year is 1999 and a jaded archaeologist named David Lambert (ph) gains access to a letter written by H.G. Wells at the end of his life, in which he confesses that The Time Machine was a real device invented by a female scientist, who was one of his many mistresses.

David becomes obsessed with finding the machine, and through flashbacks, we learn why. His own love, a fellow archaeologist named Anita, has died of a strange mad-cow-like disease. David thinks that if he can travel back through time, he can perform a life-repair -- saving not only Anita, but his own parents from their untimely deaths.

Because he's also beginning to experience mad-cow tremors himself, David suspects he has nothing to lose by hurtling into the unknown. Knowing that both H.G. Wells and Albert Einstein were skeptical about turning back the clock, David first plays it safe when he discovers the time machine and travels forward five centuries into the England of 2500 A.D.

He lands in a London congealed into a primordial soup by global warming. David records in his journal that "the lovely Gothic face of Parliament has slipped into the water, exposing a warren of chambers colonized by mynah birds, yet Big Ben still stands -- huge fig trees in its clockless eyes."

Searching for Wells mistress who preceded him into the future, and tantalized by evidence of a civil war that decimated the country, David embarks on a suspenseful trek north into Scotland. There, he stumbles upon proof that, unfortunately, not all of humankind has melted away.

A Scientific Romance is poetic, not preachy, in its vision of this grave new world. Like Wells' novel, it also taps into that most futile of yearnings: to live lost time over again. When we leave him, David is strapping himself into the time machine once more, to try to do just that: live his personal history over, even as he acknowledges that memory usually improves on life experience, or as he puts it: the echo is richer than the source.

I certainly wouldn't claim that A Scientific Romance is richer than The Time Machine, but as a literary echo, it ingeniously amplifies the desolate wail of its mournful source.

GROSS: Maureen Corrigan teaches literature at Georgetown University. She reviewed A Scientific Romance by Ronald Wright.

This is a rush transcript. This copy may not

be in its final form and may be updated.

Dateline: Maureen Corrigan; Terry Gross, Philadelphia

Guest:

High: Book critic Maureen Corrigan reviews "A Scientific Romance" by Ronald Wright.

Spec: Books; Authors; Ronald Wright; A Scientific Romance

Please note, this is not the final feed of record

Copy: Content and programming copyright 1998 WHYY, Inc. All rights reserved. Transcribed by FDCH, Inc. under license from WHYY, Inc. Formatting copyright 1998 FDCH, Inc. All rights reserved. No quotes from the materials contained herein may be used in any media without attribution to WHYY, Inc. This transcript may not be reproduced in whole or in part without prior written permission.

End-Story: A Scientific Romance

Transcripts are created on a rush deadline, and accuracy and availability may vary. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Please be aware that the authoritative record of Fresh Air interviews and reviews are the audio recordings of each segment.